The Confederate States of America

Tensions over slavery continued to dominate the national landscape in the mid-to-late 1850s. One result of the Kansas-Nebraska Act was that the Kansas Territory became a hotbed of both slave-owners and abolitionists. Neighboring Missouri was a "slave state," and many Missourians spilled over the western border into Kansas to try to influence the "popular sovereignty" vote.

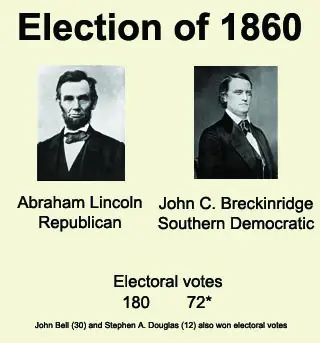

The Republican Party, meanwhile, had problems of its own, with several high-profile candidates vying for the top spot on the ticket. Senator William Seward of New York was considered the front-runner. Salmon Chase, a Senator from Ohio, was also popular. Somewhat lesser well-known were former Rep. Edward Bates of Missouri and Lincoln, whose claim to fame at that time was his series of debates with Douglas during the Senatorial campaign of 1858. At the national convention, none of the front-runners could find enough support to represent the entirety of the party, including the new West. (Along with California, Oregon was now a state. Minnesota and Iowa had also joined the Union.) Lincoln it was, as a compromise candidate, who secured his party's nomination and represented the Republican Party in the presidential race. But that wasn't the end of it. Yet another party had formed, the Constitutional Union Party. Made up of members of the other political parties (including the Whig Party) this party ran Speaker of the House John Bell as its presidential candidate. This party's main election issue was compromise to save the Union, continuing the theme begun with the Missouri Compromise and resonating through the Compromise of 1850. Compromise wasn't on the minds of most people in the North or the South and certainly not in the minds of the Democratic Party. Breckinridge proved far more attractive to Southern voters, and the Southern Democrats won 11 states and 72 electoral votes. Bell and the newly formed Constitutional Union Party carried three states and 39 electoral votes. Douglas and his (Northern) Democrats won only one state, Missouri, with 12 electoral votes, despite winning 1.3 million popular votes. The winner in the election, though, was Lincoln, carrying 18 states and 180 electoral votes, a clear majority. Many in the South believed that they had the right to remove themselves and their state from the Union. The people of South Carolina had believed this for years, as exemplified in the Nullification Crisis, in which the state asserted that its needs were paramount and the federal government's needs secondary. The threat of the mobilization of federal troops convinced the powers that were in South Carolina to back down. The idea of a state's being able to step outside the jurisdiction of the Federal Government didn't go away, however. South Carolina and the other Southern states revived it after Lincoln's election and carried out the theory to its greatest logical conclusion. Next page > The Confederacy Takes Shape > Page 1, 2, 3, 4, 5 |

|

Social Studies for Kids

copyright 2002–2026

David White

One major development in the history of American slavery was the famous Supreme Court case Dred Scott v. Sandford. In

One major development in the history of American slavery was the famous Supreme Court case Dred Scott v. Sandford. In  The conflict turned violent, leading to the name

The conflict turned violent, leading to the name  The big problem for the Democratic Party at this time, though, was that the slavery issue had sundered the party, and the country, along geographical lines. Southern Democrats eventually chose to form their own party and run their own candidate, Vice-president

The big problem for the Democratic Party at this time, though, was that the slavery issue had sundered the party, and the country, along geographical lines. Southern Democrats eventually chose to form their own party and run their own candidate, Vice-president