'Bleeding Kansas'

The pre-Civil War struggle between North and South was in sharp focus in the American Midwest in the 1850s, particularly in the Kansas and Nebraska Territories. The struggle was particularly violent at times in Kansas, leading many to call it “Bleeding Kansas.” The Louisiana Purchase had created a vast amount of new land for eastern settlers to explore and claim. As more and more states joined the Union, the question of whether slavery would be allowed in those new states was more and more in evidence. The Missouri Compromise tried to keep the balance between “slave” and “free” states, but the Compromise of 1850 left many in the South uneasy with the progress of settlement and did more to antagonize Northeners by bringing back the Fugitive Slave Law.

Missouri had been a state since 1821, and Missouri allowed its residents to own slaves. Some settlers had traveled west from Missouri before 1854; but the creation of the Kansas Territory accelerated such crossovers, particularly by pro-slavery forces wanting to influence the popular sovereignty of the anticipated new state of Kansas. At the same time, “free soil” forces, or those who opposed slavery (also called “free-staters”), were moving in to the Kansas Territory, buying land in the same way that their pro-slavery counterparts were. The issues were the same in the Nebraska Territory; but for a variety of reasons, the differences in that territory were nowhere near as severe as those in “Bleeding Kansas.”

Whatever the true motivator of people who turned violent in their disputes over the settlement of the new territory, “Bleeding Kansas” it became. The term appeared in the New York Tribune in 1856. Various attributions exist for the origin of the term; many accounts of the period attribute the term to Horace Greeley, the well-known and powerful editor of the Tribune. Whether he came up with the term or not, he certainly advocated the use of it in the pages of his newspaper. The term appeared in various forms, including in a poem by Charles Weyman: “Far in the West rolls the thunder, the tumult of battle is raging where bleeding Kansas is waging war against slavery!” The facts of the matter are that several dozen people in Kansas died, in various armed conflicts in the mid- and late 1850s.

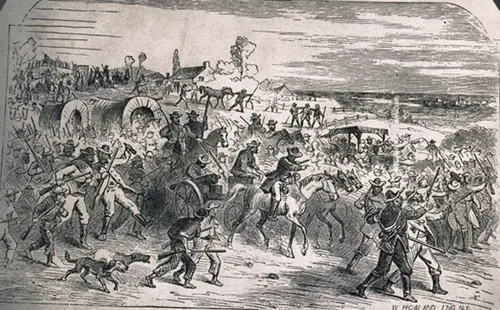

As a result, the territorial legislature that was elected in 1855 had a pro-slavery flavor to it, so much so that the “free-staters,” as they were called, refused to recognize the legitimacy of that legislature and vowed to have their own government, at their own capitol. The free-staters, who lived in places like Topeka and Manhattan, did indeed have their own legislature and declared that the capitol of the territory would be Lawrence, a free-state stronghold. Supporters of each legislature declared the other invalid. President Franklin Pierce waded in and declared support for the pro-slavery government. Tensions ran high, and it was only a matter of time until things turned violent. Lawrence, as the free-state capital, came under intense pressure from pro-slavery forces; one contingent, led by Atchison himself, sacked the city of Lawrence in May 1856. The free-state side wasn’t exactly nonviolent. Although schoolmaster Eli Thayer and his New England Emigrant Aid Company were largely pursuing a victory-by-numbers approach with the settlement of the Kansas Territory, the firebrand abolitionist minister Henry Ward Beecher was not shy about advocating violence if needed and made sure that many of the New England settlers were carrying with them Sharps rifles (which became known as “Beecher’s Bibles”).

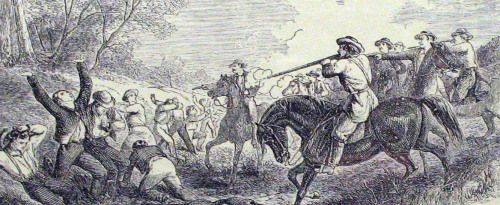

One abolitionist who was no stranger to armed conflict was John Brown (right), who came to prominence for his involvement in two violent episodes in Kansas. In response to the sacking of Lawrence, Brown and his sons killed five pro-slavery farmers in the tiny settlement of Pottawatomie. In August of that same year, Brown was involved in a tense clash between abolitionists and pro-slavery forces at the small town of Osawatomie: Brown and a few dozen men held off a few hundred opponents before retreating; the victors stormed into the town and burned it. Small bursts of guerrila action on both sides continued to punctuate the territory’s ongoing struggles, as more and more settlers on both sides arrived. In the midst of all this, another election took place, in 1857; again, the pro-slavery side won, primarily because of a boycott by free-staters. The resulting territorial government drafted a blueprint for government, called the LeCompton Constitution. It allowed slavery. Another vote occurred, on the efficacy of the LeCompton Constitution as the foundational government document of the Territory. By this time, free-staters outnumbered those who favored slavery by a considerable margin, and so when most people living in the Kansas Territory voted on the LeCompton Consitution, the result was a rejection of it and its pro-slavery platform. The violence surrounding the issue of slavery in Kansas wasn’t confined to the Kansas Territory. In one of the most shocking episodes ever in the U.S. Senate, Massachusetts Sen. Charles Sumner stood up on the Senate floor in May 1856 and gave a speech called “The Crime against Kansas,” in which he railed against the actions to extend slavery into the Kansas Territory. In particular, Sumner impugned the actions and character of Andrew Butler, an elderly Senator from South Carolina who had been particularly encouraging of pro-slavery forces in Kansas. The day after Sumner’s speech, Preston Brooks, a cousin of Butler and a member of the U.S. House of Representatives, stormed onto the Senate floor and beat Sumner with a cane. The blows were not fatal, but Sumner was very much injured.

By this time, John Brown had left to plan his raid on Harpers Ferry, Atchison had gone to join the Missouri National Guard, and other leaders on both sides had gone back to their home states, leaving Kansas settlers to struggle on. By this time, the number of free-state settlers was far higher than the number of pro-slavery settlers. The final vote on a government for the Kansas Territory was the Wyandotte Constitution, which represented the free-state viewpoint, found overwhelming success in a special election that took place in October 1859. Kansas was finally admitted to the Union on January 29, 1861. |

|

Social Studies for Kids

copyright 2002–2026

David White

In the middle of all of this strife, literally and figuratively, was Kansas. The

In the middle of all of this strife, literally and figuratively, was Kansas. The  The most common narrative among historians about this conflict is that it was over slavery. However, some historians assert that the disputes, violent thought they were, centered more on the ownership of land itself, independent of what the prospective land owners wanted to do with that land. As with many issues at this time, the shadow of the slavery conflict was long. It was entirely the case in Kansas and elsewhere in the Union that conflicts between Americans arose over land ownership but had nothing to do with slavery. Economics was a powerful motivator in many an action and dispute. The much more reported motivator of conflict during this time, especially in the wake of the advent of popular sovereignty, was the ethical, moral, and economic conflict over slavery.

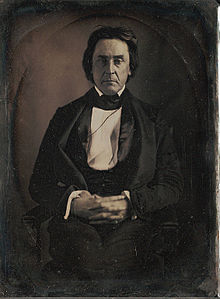

The most common narrative among historians about this conflict is that it was over slavery. However, some historians assert that the disputes, violent thought they were, centered more on the ownership of land itself, independent of what the prospective land owners wanted to do with that land. As with many issues at this time, the shadow of the slavery conflict was long. It was entirely the case in Kansas and elsewhere in the Union that conflicts between Americans arose over land ownership but had nothing to do with slavery. Economics was a powerful motivator in many an action and dispute. The much more reported motivator of conflict during this time, especially in the wake of the advent of popular sovereignty, was the ethical, moral, and economic conflict over slavery. One advocate of slavery who was no stranger to armed conflict was David Atchison (left), a Missourian who had wide influence across his state (and might even have been

One advocate of slavery who was no stranger to armed conflict was David Atchison (left), a Missourian who had wide influence across his state (and might even have been  This was in the same month in which “border ruffians” had sacked Lawrence. President Pierce, who had been on record as supporting the pro-slavery cause, called on the nation to recognize the pro-slavery government and, in July 1856, sent 500 U.S. Army troops to disperse the free-state government. A month later, John Brown fought in the Battle of Osawatomie. After the end of this battle, a fragile peace took hold, punctuated by bouts of continued guerrilla violence perpetrated by both sides. The last major violent conflict was the Marais des Cygnes massacre, in 1858; the result was five free-staters dead.

This was in the same month in which “border ruffians” had sacked Lawrence. President Pierce, who had been on record as supporting the pro-slavery cause, called on the nation to recognize the pro-slavery government and, in July 1856, sent 500 U.S. Army troops to disperse the free-state government. A month later, John Brown fought in the Battle of Osawatomie. After the end of this battle, a fragile peace took hold, punctuated by bouts of continued guerrilla violence perpetrated by both sides. The last major violent conflict was the Marais des Cygnes massacre, in 1858; the result was five free-staters dead.