The Confederate States of America

The idea of compromise in order to satisfy both Northern and Southern interests was an idea early adopted. The fiery debates of the Constitutional Convention burned red hot with topics like congressional representation and taxation. The very fabric of the government, with its two houses of Congress and its executive and judicial branches, was the result of a compromise–an overall plan that had enough elements that were palatable to enough people so that enough support was achieved in order to create the government. Both sides got something that they wanted, and both sides were willing to "give up" something in order to "get" something else. That spirit of compromise, of shared central interest that allowed North and South to effectively agree to disagree on some things as long as they also agreed on the central idea that they were better together than apart, sustained the nation through a period of intense growth. The more tensions ran high, however, the less people were willing to compromise. Eventually, divisions led to dissensions, which led to furious disagreements, which led to violence. As settlement of the continent spread westward, populations grew, and more and more states petitioned to join the Union, Congress became obsessed with maintaining some semblance of balance between North and South in terms of representation. The Southern states did not all band together on every issue, but they did, more often than not, do so when the issue came to whether to allow slavery, either in existing states or in new ones. The same was true in the North–at least in terms of not all states being in lock step all of the time; however, the issue of whether to allow slavery in new territories was one that generally united Northern interests behind stemming the spread of slavery.

Congress passed a series of compromise laws intended to stave off what many feared would be a violent resolution to the conflict over slavery. The first major such law was the Missouri Compromise in 1820. During debate on that bill, Congress debated a proposal to keep slavery out of Missouri. Congress voted down the amendment, and Missouri entered the Union as a "slave state." Also as part of the Missouri Compromise, Maine entered the Union as a "free state," prohibiting slavery. Importantly, for subsequent states seeking entrance to the Union, Congress drew a line across the southern boundary of Missouri: any new state below that line would be allowed to have slavery, and any new state below that line could disallow it.

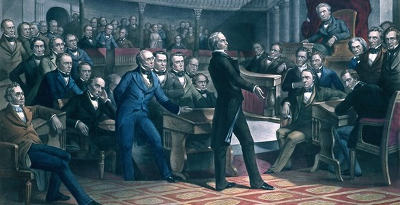

Senator Henry Clay of Kentucky was known as an astute politician who could get other people to listen to each other and even agree on certain things. He had brokered the Missouri Compromise. Later in life, he became known as "the Great Compromiser" for his ability to break Congressional deadlocks. Clay was the architect of what came to be called the Compromise of 1850. American had won a war with Mexico and gained a large amount of new territory as a result. The question of whether to allow slavery in that new territory was very much on people's minds in the late 1840s. In January 1850, he presented to the Senate a series of resolutions that he thought would, in some way, appease both North and South.

To satisfy Southern interests, Clay argued that the federal government should appropriate the part of New Mexico Territory claimed by Texas and give it to New Mexico, paying Texas for the land. Also to satisfy Southerners, Clay championed a more stringent Fugitive Slave Law, one that introduced punishments for people known to have broken the law and a federal patrol whose function was to enforce the law. (This, in effect, made the original statute, which devolved responsibility to the states, into a federal one, with the financial and military power of the national government behind it.) To satisfy Northern interests, Clay championed the admission of California as a "free state" and the abolition of the slave trade in the District of Columbia. The Compromise of 1850 had enough for everyone to support most of it, and it became the law of the land. However, the spirit of compromise was on the wane. Next page > Slavery and a Sundering > Page 1, 2, 3, 4, 5 |

|

Social Studies for Kids

copyright 2002–2025

David White