The New World Slave Trade

The slave trade sent millions of captured Africans and people from other countries to often horrendous conditions in the New World, time and again, for several centuries. European slave traders arrived in West Africa in the late 15th Century, but Africans had been enslaving other Africans long before Europeans arrived.

Slavery was an ancient institution. The civilizations of Ancient Greece and Ancient Rome, to whom so many people in Western societies have looked for examples of how to live, had economies that incorporated the use of slaves. Older civilizations, such as Mesopotamia and Egypt, had similar traditions.

Certainly in Africa, the practice of enslaving other people was well established by the time that Europeans arrived in the late Middle Ages. Africans were enslaved as the result of a loss in battle or a raid by opportunistic militants or even to pay off a debt. As well, Africans enslaved other Africans in order to sell them for money and goods, just as Europeans later did. Also at this time, most of the Middle East and parts of northern Africa were controlled by Muslim societies, some of whom engaged in the slave trade as well. African slave caravans going east were not an uncommon site. Various justifications were given by European powers for adopting the practice of buying and selling slaves in order to produce workers. The explorations of the New World had resulted in new economic opportunities for the Western European powers, and the demand for people to do the work needed to harvest sugar cane, tobacco, and cotton was also higher than the European powers' ability to provide. As more and more Europeans explored more and more of the New World, more Europeans followed in the footsteps of those explorers in order to settle, find a home, and find economic opportunity. The need for labor proliferated. Much of this labor was backbreaking at best and life-threatening at worst. One practice adopted in North America was indentured servitude, the idea that one person would agree to for work another person for a number of years, exclusively, after which the worker was free to go and, in some cases, take with him or her some money or even land provided by the "employer." Many Europeans eventually decided that the risks were better taken by enslaved Africans than by Europeans themselves. A common belief at the time, fueled occasionally by religious teachings, was that white Europeans were superior to black Africans and so slavery was, in some way, seen to be not as reprehensible as some people thought. Slave owners at this time cited examples from Ancient Greece and Ancient Rome, which involved enslavement of Greeks by Greeks and Romans by Romans. (They also routinely enslaved people from other civilizations as well, probably in greater numbers.)

Portugal, an early leader in exploration of Africa and the New World, was long the leading exporter of African slaves. Beginning in 1440, Portugal made a habit of stopping at São Tomé and other ports, there to trade money, weapons, and other goods for enslaved people, whom the Portuguese would sell elsewhere–in South America and in the Caribbean. (Western Europe at this time also had a small market for slaves.) To facilitate their exploration, Portuguese sailors had established trading posts along Africa's western coast; it was at these trading posts that many slaves left Africa forever. Many of these trading posts were manned by people with weapons; in effect, they were trading "forts." One of the most well-known of these was Elmina, founded in 1482 on the Gold Coast, what is today Ghana. It was called the Gold Coast because gold was in ready supply. Another Portuguese trading settlement was on the island of Gorée, in the harbor of what is now Dakar, Senegal. France, Great Britain, and the Netherlands also coveted the island and its port and trade. In fact, an order by trading volume of the major European slave-trading nations would be this:

Ouidah was a commercial center in what is now Benin, along the Bight of Benin. The name that Europeans gave to this area was the Slave Coast. Many historians think that, during a 200-year period, Ouidah by itself was the embarkation point for a million African slaves.

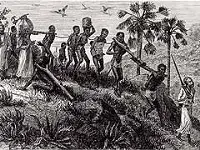

Some enslaved people were taken from places nearby ports. Other people were seized farther inland and forced to walk, often shackled and even yoked together, for hundreds of miles to the western ports.

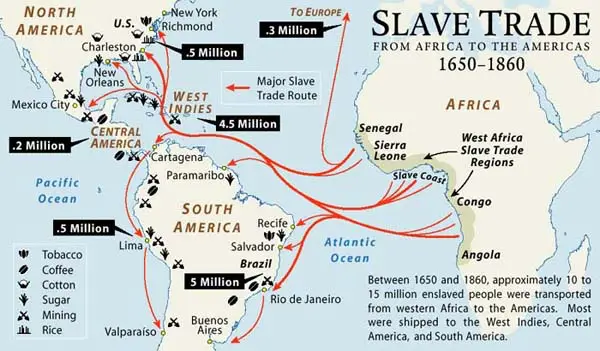

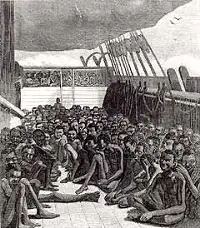

And, when these enslaved people finally arrived at slave ports, they often had to wait until the next slave ship arrived. European slave traders had special facilities in which to keep such slaves. One of the more common was the barracoon (Spanish for "barracks"), a wooden hut that functioned as a holding area and was usually heavily guarded. When slave ships arrived, slave traders would examine potential slaves at a market, poking and prodding and otherwise manhandling the Africans with an eye toward how much money they would bring when they were sold in the New World. Those who were accepted soon left on the ships. Those who were rejected were left to an uncertain fate: if they were sold to a subsequent ship, then they had to endure a potentially dangerous journey across the Atlantic Ocean to a new "home"; alternately, they were pressed into service in some fashion at the port itself; at the worst, they were summarily killed, for not being "worth anything." As the 15th Century ended, Portugal celebrated the voyage of Vasco Da Gama to India while also setting up sugar plantations on various ocean locations, including Madeira and the Canary Islands. The Western European powers were actively seeking trade routes to the Far East that didn't require the time and effort of the land-based travel along the fabled Silk Road, to China and waypoints in between. Also, with the fall of Constantinople in 1453, such trade routes were often dangerous. For both of those reasons, European governments and businessmen coveted seaborne routes to the Far East and the New World. Both Spain and Portugal sent a considerable number of slaves to the New World as forced labor. The first, a shipment of Spanish slaves, are thought to have arrived not long after the turn of the 16th Century, on the island of Hispaniola, now the Dominican Republic and Haiti. Slave ships soon began arriving elsewhere in the Caribbean, at Cuba and Jamaica, and then further west, to Central America, in the next few decades. The first ship containing slaves to arrive in what is now the United States did so in 1619, in the Virginia colony.  Estimates are that as many as 12.5 million people were enslaved in Africa and sent across the Atlantic Ocean, through the dreaded Middle Passage, to the New World. At its height, in the mid-18th Century, the slave trade transported more than 80,000 Africans a year to the New World. The highest percentage of these enslaved people ended up in the Caribbean islands; slightly fewer went to Brazil; not one-quarter of all of those enslaved went to Spanish possessions in North and South America; and the smallest percentage went to British America and the United States. Conservative estimates are that as many as 15 percent of those who were forced aboard such ships did not survive the journey. At first, Europeans who engaged in the slave trade used cargo ships to transport enslaved people. It wasn't long, however, until Europeans built ships designed to carry slaves. Cargo and other smaller ships could transport a few dozen slaves; purpose-built slave ships could carry several hundred.

Not all slave ships confined their "cargo" to belowdeck. Some slaves stayed on deck during the journey, often performing tasks to assist or replace the crew. They were chained at various times during the journey–sometimes with wrist manacles, sometimes with leg shackles, and sometimes with both. It was the goal of slave traders to deliver living slaves, so the victims were given food, often just enough to stay alive. Slaves were also often made to dance or do some form of exercise in the sometimes short amount of time that they had on deck. A ship's captain and crew kept slaves in line by keeping them in chains and, at other times, brandishing guns and other weapons. Discipline was harsh, and the slightest infractions were punished by beatings and, in the case of women, other kinds of physical attacks. The British colonies in North America engaged in Triangular Trade with the Mother Country; one part of that triangle was the shipment of enslaved people from Africa to the New World. One common stop for these slaves was Santo Domingo, now the capital of the Dominican Republic and then a very busy international slave port. The island was a French colony, and French troops quickly crushed a slave rebellion in 1522, reminding anyone who sought freedom that they risked paying a very dear price for it. It wasn't always African people who were enslaved. One of the first several slave vessels built in the American colonies, the Desire, had its origins in the Massachusetts colony and transported Native American slaves to Bermuda in exchange for cotton, salt, tobacco, and African slaves. The flip side of this is that a certain number of Native Americans and African-Americans owned African slaves as well. By and large, the people and countries who engaged in the slave trade found it profitable, sometimes very much so. The money gained in exchange for sugar, tobacco, coffee, rice, and the several other things produced on the back of slave labor was invariably more than enough to justify the use of such slave labor. This was true not only in Western Europe but also in West Africa.

In the United States, slave labor powered the production of cotton, a prime commodity sold on the open market in Europe, most prominently in Great Britain. Harvesting of tobacco also depended on slave labor. Living and working conditions in the fields and plantations were often brutally harsh; slave owners had in mind that they could always find another set of forced workers. The slave trade carried on for a few hundred years, reinforced in various places by economics, certainly, but also by laws protecting the practice of enforced servitude. Eventually, though, every country stopped trading in slaves. Denmark, not a major contributor but still involved, was the first to stop, passing a law in 1792 that took effect in 1803. Four years later, both Great Britain and the United States passed laws outlawing further importation of slaves. (The U.S. action did not abolish the slave trade within the country, which continued to thrive until the advent of the 13th Amendment in 1865.) In Great Britain, the 1807 law stopping the slave trade did not end the practice of slavery in British colonies. That came later, in 1833, thanks in large part to the efforts of William Wilberforce. In the U.S., the passage of laws banning slave importations did not stop the practice, however. Smuggling of slaves into the U.S. continued until 1859. The last known slave ship to bring Africans to America was the Clotilde, which arrived in Mobile, Ala., two years before the Civil War began. The slave trade carried on in Brazil. That country was the last to ban the transatlantic slave trade, in 1831. Brazil outlawed slavery in its entirety in 1888. |

|

Social Studies for Kids

copyright 2002–2026

David White