Edwin Stanton: Lawyer, Secretary of War

Edwin Stanton was a lawyer and government official who was most well-known for serving as Secretary of War during the American Civil War.

He was born on Dec. 19, 1814, in Steubenville, Ohio. His father died when young Edwin was 13, and the teen left school, to work in a bookstore so he could support his widowed mother. He continued his studies part-time and later attended Kenyon College and also trained to be a lawyer. He got admitted to the bar in 1836 and worked in Pittsburgh for a time; he then moved to Washington, D.C., and built up a large-scale, well-known law practice. He argued several cases before the U.S. Supreme Court. In 1836, he had married Mary Lamson; they later had two children. Mary died in 1844, and Stanton remarried, to Ellen Hutchinson; they had four children. In 1855, Stanton was the defense lawyer in a case for which Lincoln was later added to help with the defense. The two did not hit it off, and Stanton refused to let Lincoln participate in the trial. Lincoln stayed in Cincinnati and watched the trial, later saying that he learned a lot from watching Stanton operate.

Stanton was a defense lawyer in a high-profile case in 1859. Rep. Daniel Sickles of New York had killed another man, Philip Key, on the suspicion that Key and Sickles's wife had been more than friends. Sickles, facing a capital murder charge, hired two prominent lawyers, who asked Stanton to join their defense team. Stanton advanced the theory that Sickles had committed murder during a temporary bout of insanity. The jury agreed and found Sickles not guilty. It was the first use of such an insanity plea in American legal history. President James Buchanan appointed Stanton as Attorney General in December 1860. Stanton served in that position for only a few months because the new President, Abraham Lincoln, took office on March 4, 1861 and named Pennsylvania Senator Simon Cameron as the Secretary of War.  When the Civil War began the following month, Cameron found himself overseeing an army and command structure that weren't quite ready to fight the kind of war that would be needed. Union troops suffered a humiliating defeat at the First Battle of Bull Run, in August 1861. Another such defeat, at Ball's Bluff in October, resulted in a congressional Joint Committee on the Conduct of the War. Many in government criticized Cameron's handling of the situation. Toward the end of the year, Cameron delivered to Lincoln a report on the state of the war; in that report, Cameron argued that it might be time to consider arming African-Americans and including them in the Union force. Stanton, whom Cameron had called in to advise him, urged Cameron to be as explicit as possible with this recommendation. An alarmed Lincoln advised Cameron to remove the recommendation before circulating the report; Cameron refused, and Lincoln fired Cameron. In January 1862, Lincoln, unaware of Stanton's involvement in the report, appointed Stanton to replace Cameron as Secretary of War. The tireless Stanton reorganized the War Department, doubling the size of its staff, and convinced Congress to allow the War Department to seize control of the railroads and the telegraph lines when a military need for them arose. He also dedicated a significant portion of his workforce to rooting out corruption within government and spies inside government and out. One of Stanton's rare missteps came in spring 1862, when he ordered the shuttering of all military recruiting offices. Like many others, he thought that the war would soon be over. Another defeat at Bull Run convinced him otherwise, and the Union went to work on recruiting more soldiers. A year later, he urged support for Lincoln's establishment of a federal draft law. Despite their earlier relationship, Lincoln and Stanton got along quite well for the duration of the war. Stanton supported Lincoln's idea to issue the Emancipation Proclamation and returned to his advocacy of employing African-Americans in the Union army. Lincoln eventually agreed to do this, and two results were the 54th Massachusetts attack on Fort Wagner, in Georgia, in 1863 and the presence of United States Colored Troops at the Battle of Petersburg in 1864. Stanton remained Secretary of War throughout the conclusion of the war and afterward. The conflict ended with Stanton's reputation burnished, as an organizer and an administrator.

Stanton was one of two other couples that Lincoln had invited to accompany him and his wife, Mary, to the theater on April 13. As he had other times, Stanton refused. He was in bed later that night when he heard the news that Secretary of State William Seward had been attacked. When Stanton's wife told him that she had seen a suspicious-looking man outside their house, Stanton became angry, and ignoring her pleas, left the house to go see Seward. When Stanton arrived, he found Seward wounded and was also told that Lincoln was in a bad way as well. Stanton went to Petersen House, across from Ford's Theatre, the site of the attack on the President. Stanton was a Lincoln's side when he died and said, "Now he belongs to the ages." Stanton, as Secretary of War, was in charge of not only the armed forces but also national security. He ordered an investigation into the murders of Lincoln and Seward; locked down the city of Washington, D.C.; put all soldiers on high alert; ordered top Union general Ulysses S. Grant to come to Washington; and stopped all rail traffic out of the city. To the War Department's own manpower Stanton added the New York Police Department and the U.S. Secret Service. The investigators quickly took a number of prisoners and eventually found all who had been involved in the assassinations. All known conspirators were tried and convicted, and most were executed.

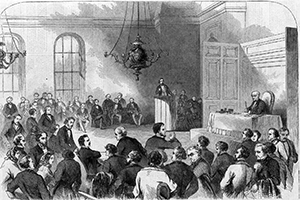

Stanton continued as Secretary of War under the administration of the new President Andrew Johnson. Stanton and Lincoln had discussed the latter's plans for Reconstruction at great length, more than Lincoln had with Johnson. The new President at first vowed to continue with his predecessor's plans regarding Reconstruction. However, Johnson preferred to take different courses of action on several key points, and this led to a series of intense disagreements with Stanton. Johnson eventually told Stanton that he was being replaced as Secretary of War. This kind of removal of a Cabinet member by a President was not unknown. However, Congress had, in 1866, passed the Tenure of Office Act, which required the President to gain the consent of the Senate before removing any member of the Cabinet. Johnson had vetoed the Tenure of Office Act but had been overridden by a determined Congress. Johnson's firing of Stanton spurred the House into action, and soon Johnson was facing 11 articles of impeachment, on charges of violating the Tenure of Office Act–in effect, breaking the law. Under the U.S. Constitution, the House votes to impeach and the Senate votes to convict. So, technically, Johnson was impeached, then his case went to the Senate. At the end of an impassioned two-month trial, the Senate voted 35-19 to convict. They needed 36 in order to get the two-thirds required by the Constitution. By a one-vote margin, Johnson kept his job. Not long afterward, Stanton resigned. The former Secretary of War returned to his law practice. His health, taxed fully during the Civil War, deteriorated during the next few years. He struggled with asthma and other ailments. In 1869, then-President Grant nominated Stanton to the U.S. Supreme Court. This occurred on December 19, Stanton's birthday. He died five days later; he was 55. |

|

Social Studies for Kids

copyright 2002–2025

David White