The Election of the President Throughout U.S. History

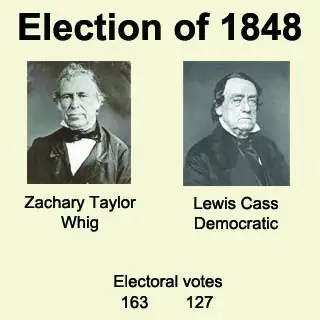

Part 3: 1844 to 1868 The Election of 1844 One of the defining issues of the 1844 campaign was the annexation of Texas. Americans settling in what was then the western part of the country increasingly struggled for influence and land with people from Mexico who lived on land that used to be Spanish territory. The cries of "Remember the Alamo" were fresh in Americans' minds. As well, the idea of "Manifest Destiny" was taking hold, and Americans were keen on expanding their frontiers. Polk's support for the annexation of Texas provided enough of an advantage for him, giving him a majority of the states and 170 electoral votes to Clay's 105. The Election of 1848 President Polk had promised not to seek re-election, and he he kept his promise. The Democratic Party chose Lewis Cass as their standard-bearer. The Whigs chose the war hero Taylor. In a very close election, Taylor converted his wartime success into political success and defeated Cass 163-127. Among the new states to vote in this election were Florida, Iowa, Texas, and Wisconsin. The Election of 1852 In the election of 1852, the Whig Party again cast aside its incumbent President in favor of a war hero. This time, the choice was Winfield Scott, a Virginian was was at the time the Commanding General of the U.S. Army. Franklin Pierce, a relatively unknown candidate, represented the Democrats. Pierce had served in the Mexican-American War and had represented New Hampshire in Congress. When the Democratic Party couldn't decide between Michigan Senator Lewis Cass and former Secretary of State James Buchanan, Pierce emerged as a compromise choice. He proved popular enough with his fellow Democrats after 50 ballots, and he proved very popular with the rest of the country, winning the election 254-42. The issue of slavery was very much an issue in the country, and it split both parties slightly along political lines, with the Southern Rights Party running a candidate and Scott's anti-slavery stance very much a turnoff for southern voters. The Whig Party had already begun to disintegrate, and the 1852 defeat was effectively its death knell. Many southern Whigs joined the Democratic Party. Others joined one of two new political parties, the Republican Party, which formed in 1854, and the "Know-Nothing" Party, which had a comet-like zenith in the next few years. The Election of 1856

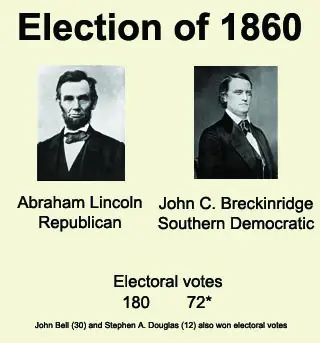

Buchanan won a majority of the electoral votes, 174-114. Fillmore's Whigs won Maryland and got eight electoral votes. Election results showed that Fremont had next to no support in the South, foreshadowing what the Republican Party could expect at the next election. The Election of 1860

The Republican Party, meanwhile, had problems of its own, with several high-profile candidates vying for the top spot on the ticket. Senator William Seward of New York was considered the front-runner. Salmon Chase, a Senator from Ohio, was also popular. Somewhat lesser well-known were former Rep. Edward Bates of Missouri and Lincoln, whose claim to fame at that time was his series of debates with Douglas during the Senatorial campaign of 1858. At the national convention, none of the front-runners could find enough support to represent the entirety of the party, including the new West. (Along with California, Oregon was now a state. Minnesota and Iowa had also joined the Union.) Lincoln it was, as a compromise candidate, who secured his party's nomination and represented the Republican Party in the presidential race. But that wasn't the end of it. Yet another party had formed, the Constitutional Union Party. Made up of members of the other political parties (including the Whig Party) this party ran Speaker of the House John Bell as its presidential candidate. This party's main election issue was compromise to save the Union, continuing the theme begun with the Missouri Compromise and resonating through the Compromise of 1850. Compromise wasn't on the minds of most people in the North or the South and certainly not in the minds of the Democratic Party. Breckinridge proved far more attractive to Southern voters, and the Southern Democrats won 11 states and 72 electoral votes. Bell and the newly formed Constitutional Union Party carried three states and 39 electoral votes. Douglas and his (Northern) Democrats won only one state, Missouri, with 12 electoral votes, despite winning 1.3 million popular votes. The winner in the election, though, was Lincoln, carrying 18 states and 180 electoral votes, a clear majority. Following through on a pre-election threat, many of the Southern states voted to secede from the Union. When Lincoln took office, the country was at war. The Election of 1864 Lincoln ran for re-election in 1864. His opponent from the Democratic Party was former General George McClellan. By this time, three new states had joined the Union: Kansas, Nevada, and West Virginia. (Eleven Southern states were not part of the Union at this time and so did not vote in the presidential election.) The election campaign was relatively straightforward: Should Lincoln be allowed to continue as President and continue the war? McClellan, who had once been in charge of the Army of the Potomac and who had found one well-known battlefield victory (Antietam) but relatively few other successes, ran on an anti-war ticket, but the recent Union success in the South, notably the seizure of Atlanta, helped Lincoln to a relatively dominant re-election, 212-21. It was the first presidential re-election since Andrew Jackson's victory in 1832. Lincoln had replaced his Vice-president, Hannibal Hamlin, with a Democrat, Andrew Johnson of Tennessee. The Election of 1868 Following what by then had become something of a tradition, the Democratic Party cast aside its incumbent President in favor of a new candidate, former New York Gov. Horatio Seymour. Opposing him on the Republican side was Ulysses S. Grant, the victorious general who had brought the Civil War to a close. Continuing a trend that has still to run its course, the popular vote was relatively close but the electoral vote was not. Grant won just more than 3 million votes across the country (including in the newly admitted state of Nebraska), and Seymour received 2.7 million. Grant, however, dominated in the Electoral College, winning 214-80. Mississippi, Virginia, and Texas had not be readmitted to the Union in time for this election, and residents of those three states were ineligible to vote. |

|

Social Studies for Kids

copyright 2002–2025

David White

With the death of the Federalist Party, the election was left to the Whigs and Democrats to contest, and the standard-bearers were Clay, for the Whigs, and Democrat

With the death of the Federalist Party, the election was left to the Whigs and Democrats to contest, and the standard-bearers were Clay, for the Whigs, and Democrat  The annexation of Texas accelerated a growing conflict between the U.S. and Mexico, and the

The annexation of Texas accelerated a growing conflict between the U.S. and Mexico, and the  Taylor, who had been courted by the Democratic Party as well after his wartime successes, had wanted the famed

Taylor, who had been courted by the Democratic Party as well after his wartime successes, had wanted the famed  The idea of Popular Sovereignty was cemented in the

The idea of Popular Sovereignty was cemented in the  The conflict turned violent, leading to the name

The conflict turned violent, leading to the name  The big problem for the Democratic Party at this time, though, was that the slavery issue had sundered the Party, and the country, along geographical lines. Southern Democrats eventually chose to form their own party and run their own candidate, Vice-president

The big problem for the Democratic Party at this time, though, was that the slavery issue had sundered the Party, and the country, along geographical lines. Southern Democrats eventually chose to form their own party and run their own candidate, Vice-president  The war dragged on for year after year, with hopes of a quick victory long gone. Both sides claimed victories, and neither side showed any signs of surrendering. The war in its fourth year was looking to be a war of attrition, which gave the Union the advantage.

The war dragged on for year after year, with hopes of a quick victory long gone. Both sides claimed victories, and neither side showed any signs of surrendering. The war in its fourth year was looking to be a war of attrition, which gave the Union the advantage. The end of the Civil War brought with it major civil unrest. The rigors of

The end of the Civil War brought with it major civil unrest. The rigors of