The Election of the President Throughout U.S. History

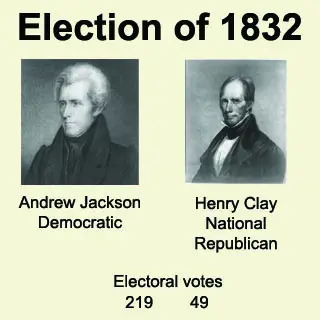

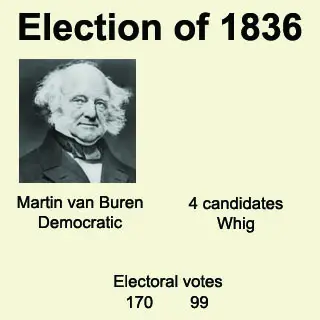

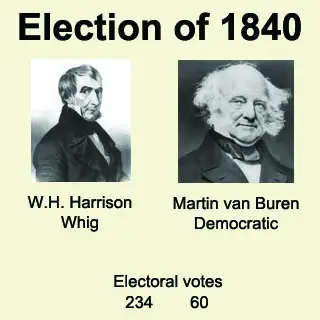

Part 2: 1816 to 1840 The Election of 1816 The American people were, by and large, happy with the direction of the country under the current political party. Madison retired, making way for his Secretary of State, James Monroe, who enjoyed his party's favorable view following the end of the war. New York Senator Rufus King, the Federalist candidate, won just three of the 19 states (and not his home state, New York). Monroe secured 183 electoral votes to King's 34. The Democratic-Republican dynasty continued. The Election of 1820 This wasn't evident in the presidential election campaign, however. The Federalist Party was in decline, and Monroe ran for re-election unopposed. He and others in the Democratic-Republican Party labeled Monroe's term the "Era of Good Feelings." Monroe won the electoral votes of all 24 states and would have received all 232 votes if one elector from New Hampshire hadn't cast his vote for John Quincy Adams, the Secretary of State. Thus, George Washington remains the only President elected unanimously. The Election of 1824 The four men split the vote such that none of them received a majority. Jackson's 99 was the highest total. (Quincy Adams totaled 84, Crawford got 41, and Clay won 37.) But the overall total was 261. The winner needed 131. As in 1800, the election was decided by the House of Representatives, with each of the 24 states having one vote. The President would be the man whose name was preferred by 13 states. As the fourth-highest vote-getter, Clay was disqualified. He was still a Representative from Kentucky, however, and the Speaker of the House; as such, he had considerable influence. He used this influence to secure 13 votes for Quincy Adams. Seven states voted for Jackson and four for Crawford. Not long after Quincy Adams was declared the winner, he named his Cabinet, including the announcement of Clay as Secretary of State. The Election of 1828 These two men formed what would become a new political party. Losing the Republican part of the name, they formed the Democratic Party. (In response, Quincy Adams and his supporters called themselves the National Republican Party.) During the election campaign of 1828, the two parties engaged in a previously unsurpassed amount of public mudslinging, with personal attacks being the norm. When the electoral votes were counted, however, it was a clear victory for Jackson, 178-83. Quincy Adams had received about the same amount of support as in the previous election, this time with one fewer electoral vote. The Election of 1832 Calhoun himself had resigned in July so he could run for the Senate to represent his home state of South Carolina. Later that year, Calhoun led a drive by his home state to "nullify" a tariff passed by the federal government. Jackson responded by threatening to send federal troops to South Carolina. The result of the Nullification Crisis was a further division between North and South and, specifically, between the South and the federal government. In the election of 1832, Jackson's opponent was Henry Clay, and the result was a blowout, 219-49. A third-party candidate, William Wirt, won Vermont's 7 electoral votes for his Anti-Masonic Party. The Election of 1836 Like the Democratic-Republicans in 1824, the Whigs could not decide on one candidate and so ran four. The most well-known of these were William Henry Harrison and Daniel Webster. Also on the ballot were Hugh White and Willie Mangum. Jackson was still very popular, and so his "blessing" of van Buren resulted in the latter's victory, with 170 of 269 electoral votes. The Whig vote was split along regional lines, as Harrison, of Ohio, gained most of the non-van Buren votes. White, of Tennessee, got much of the midwestern vote. Webster, of Massachusetts, had support in New England. And Mangum, of North Carolina, won the southern Whig vote. Van Buren managed to keep the Democratic Party united behind him, for this election, anyway. The Election of 1840 Unlike during the previous campaign, the Whigs rallied behind one candidate in the election of 1840, William Henry Harrison, "Tippecanoe," a her of the War of 1812. propelling William Henry Harrison to a lopsided victory, 234-60. Harrison had scant time to enjoy his victory, however, because he died after just a few weeks in office from an illness that ended in pneumonia. His Vice-president, John Tyler, was a former Democrat who, after assuming the Presidency, did his best to block the Whig Party that Harrison had been elected to advance. In return, Tyler was ostracized by the Whig Party and found himself without a party to represent in the election of 1844. |

|

Social Studies for Kids

copyright 2002–2024

David White

The war dominated Madison's second term as president, as did westward expansion. The war ended in 1814 (although the Battle of New Orleans was fought after the peace agreement was reached). The

The war dominated Madison's second term as president, as did westward expansion. The war ended in 1814 (although the Battle of New Orleans was fought after the peace agreement was reached). The  The United States in 1820 was showing signs of the divisions that would result in the Civil War four decades later. Foremost of these was the

The United States in 1820 was showing signs of the divisions that would result in the Civil War four decades later. Foremost of these was the  That one vote in 1820 was not the last electoral vote that Quincy Adams received. As one of four prominent Democratic-Republican candidates in the election of 1824, Quincy Adams won a lot more. With the Federalist Party effectively gone, the Democratic-Republicans began struggling among themselves for supremacy. Quincy Adams, from Massachusetts, represented the "old guard" of New England, which had traditionally been Federalist territory. Monroe's Secretary of Treasury William Crawford was from Georgia and represented southern interests. The other two candidates were from western states:

That one vote in 1820 was not the last electoral vote that Quincy Adams received. As one of four prominent Democratic-Republican candidates in the election of 1824, Quincy Adams won a lot more. With the Federalist Party effectively gone, the Democratic-Republicans began struggling among themselves for supremacy. Quincy Adams, from Massachusetts, represented the "old guard" of New England, which had traditionally been Federalist territory. Monroe's Secretary of Treasury William Crawford was from Georgia and represented southern interests. The other two candidates were from western states:  Jackson was publicly dismayed at the election outcome and began what became a four-year campaign against Quincy Adams. Already popular with many people in the west, Jackson solidified his position as a powerful political leader with an alliance with

Jackson was publicly dismayed at the election outcome and began what became a four-year campaign against Quincy Adams. Already popular with many people in the west, Jackson solidified his position as a powerful political leader with an alliance with  Jackson proved a very popular President and easily won re-election in 1832, despite a scandal the year before that resulted in the resignation of most of his Cabinet. Significantly, Jackson had replaced his Vice-president, John C. Calhoun, with

Jackson proved a very popular President and easily won re-election in 1832, despite a scandal the year before that resulted in the resignation of most of his Cabinet. Significantly, Jackson had replaced his Vice-president, John C. Calhoun, with  When Jackson won re-election, he brought with him van Buren, who ran for the presidency in 1836 when Jackson retired. Two years before, a new political party had emerged, the

When Jackson won re-election, he brought with him van Buren, who ran for the presidency in 1836 when Jackson retired. Two years before, a new political party had emerged, the  The

The