Ptolemy I of Egypt

Ptolemy I was the founder of a dynasty of Egyptian leaders that lasted for three centuries, ending with the rule of Egypt's last pharaoh, Cleopatra VII. He is also known for advancing the development of Alexandria and for commissioning two of its most famous landmarks, the Great Library and the Pharos Lighthouse.

The first pharaoh named Ptolemy was a friend and biographer of the famed conqueror Alexander the Great, succeeding him as ruler of Egypt after the young Macedonian's death. Ptolemy was born in 367 B.C. in Macedonia into a noble family. He was older than Alexander and knew the royal prince as they were growing up. They are known to have studied together under the great philosopher Aristotle. Ptolemy supported Alexander in his struggle with his father, Philip II, and loudly proclaimed Alexander's right to be king when his father was killed. For this, the new king rewarded his friend and confidant Ptolemy with a position in the royal household, advising the king on matters military and domestic. He later became one of Alexander's personal bodyguards. Ptolemy supported the expedition against Persia and was with Alexander at most of the famous events in the king's life: the defeats of Darius at Issus and Gaugamela, the journey to the oracle in the Siwa desert, the sojourn into India (during which he served as Alexander's second-in-command). When Alexander died, in 323 B.C., he left a power vacuum. On his deathbed, he supposedly responded to the question of who should succeed him with the words "Whoever is the strongest." Ptolemy was one of several generals who strove to be exactly that. Alexander had complicated matters slightly by handing his signet ring, perceived as a symbol of power, to Perdiccas, the leader of the cavalry. Perdiccas took that action as a tacit acknowledgement of his being designated Alexander's regent, or successor. Ptolemy and other commanders advocated for a division of the empire. This dispute continued for several years. The successors were known as the Diadochi, and their internecine struggles continued for decades. A large contingent of the army accompanied Alexander's body back west. (He had died in Babylon.) The intent of the convoy carrying the royal body was to deposit in a tomb that had been purpose-built in Aegea, Macedonia's religious capital. When the convoy reached Damascus, Ptolemy made such an impassioned case for knowing that Alexander really wanted to be buried in Egypt that the convoy changed course. Ptolemy had an altar built at Siwa, location of the oracle who had proclaimed Alexander the living son of Zeus Ammon. Alexander's body, kept in Memphis for a time, ended up in Alexandria, the dynamic city that Alexander had founded and designed and that Ptolemy had helped develop. One of history's great mysteries is what happened to the sarcophagus because it disappeared one day and has yet to be found.

Ptolemy, meanwhile, set about taking control of various parts of the Middle East. He claimed Egypt as his own and declared Alexandria his capital. While other of Alexander's generals were fighting over control of the rest of the Macedonian Empire, Ptolemy declared Egypt independent and focused on developing an empire there. He had to fight back a serious challenge from Perdiccas, who launched multiple attacks on Ptolemy's forces for several reasons, not the least of which was his anger at Ptolemy's diversion of Alexander's sarcophagus. The Egyptian force was more than up to the task of defending itself, and Ptolemy's victory led to Perdiccas's own officers dispatching their leader. Some sources say that Alexander's other generals offered to make Ptolemy regent but that he refused, preferring to stay in Egypt. Ptolemy marched at the head of his army in another struggle to fill the void left by Alexander. The opponent this time was Antigonus, who had taken over control of the main army. Ptolemy and two other former commander, Cassander and Lysimachus, joined forces and defeated a large force led by Antigonus's son, Demetrius at Gaza in 312 B.C. The peace agreement that followed confirmed Ptolemy as the rightful ruler of Egypt. One of his first acts was to remove from office Alexander's chosen representatives, Cleomenes, who taken advantage of the Macedonian army's absence to declare himself the satrap in charge of Egypt. Ptolemy, backed by his army and by the Egyptian people, who saw him as Alexander's successor, succeeded in having Cleomenes convicted of embezzlement and executed. Firmly in control, Ptolemy turned his administrative acumen to a reorganization of various elements of Egyptian society, notably the economy and the governmental apparatus. He also took the Egyptian name Meryamen Setepenre. One of Ptolemy's rare missteps was to introduce a new religion, with a new god named Serapis, the god of healing. It was an attempt to combine the Egyptian and Greek traditions. The local population didn't take too kindly to the new tradition, and it eventually faded away. The Egyptians were called into battle again in 306 B.C., fighting on land and at sea. Ptolemy's forces defeated Antigonus and his army, again at Gaza; in the same year, however, the Egyptians lost a naval battle to Antigonus's son, Demetrius, at Salamis. It wasn't until 301 B.C., at the Battle of Ipsus, that the restless Antigonus was finally subdued: He was killed in the battle.

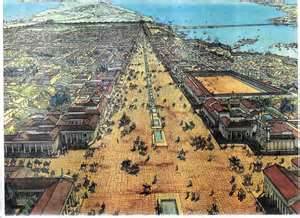

For the better part of two decades, from 306 B.C. to 286 B.C., Ptolemy shored up his defenses, creating a buffer zone of sorts by conquering Palestine, the coastal part of Syria, and Cyprus. He moved the capital from Memphis to Alexandria and commissioned great building projects, among them the Pharos Lighthouse, one of the Seven Wonders of the Ancient World; the Great Library of Alexandria; and the Mouseion, a university envisioned by Alexander. Also during this time, Ptolemy wrote a biography of Alexander and his campaigns. (This account has been lost, but the famous Alexander biographer Arrian used it as one of his sources for his Anabasis.) Along with Alexander in Susa, Ptolemy had married a Persian princess in a giant ceremony. In Egypt, he married again, several times, and was father to 11 children. In 285 B.C., Ptolemy stepped down, leaving the throne to his son, who at age 22 became Ptolemy II. The elder Ptolemy died two years later and was proclaimed by his son as Theos Soter ("God and Savior"). He had gained the title of Soter (Savior) a few years earlier, for defending Rhodes against Demetrios; thus has he been referred to by historians as Ptolemy I Soter. |

|

Social Studies for Kids

copyright 2002–2026

David White