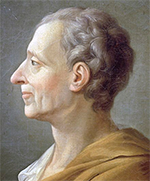

The Philosophe Montesquieu: Champion of Laws and Liberty

Charles-Louis de Secondat, the baron de Montesquieu was one of France's most famous Enlightenment philosophers and writers. His 1748 work The Spirit of Laws formed the basis for both the Declaration of the Rights of Man and Citizen and the U.S. Constitution.

He was born Charles-Louis de Secondat on Jan. 18, 1689, at the castle of La Bréde, near Bordeaux. His father was a soldier family from a wealthy family. His mother died when the boy was 7. Four years later, he went to Meaux, to the Oratorian Collége de Juilly, in order to get a classical education. He earned a law degree from the University of Bordeaux in 1708 and went to work in Paris. Charles-Louis returned to Bordeaux when his father died, in 1713, to manage the family estates. The following year, he went to work as the presiding officer for the Tournelle, the criminal division of the Bordeaux Parlement; in this capacity, he heard legal cases and acted as prison supervisor. He got married, to Jeanne de Lartigue, and then inherited a large amount of land and money when his uncle Jean-Baptiste died the following year. He then became the Baron de La Bréde and de Montesquieu. He and Jeanne had three children together. Montesquieu rededicated himself to his studies, which included the sciences, history, and Roman law. He also was a writer and published books, beginning in 1721 with a satire titled Persian Letters. The novel consisted of a set of letters written between two Persians, Rica and Usbek, who travel throughout Europe and write to each other about what they experience. Using non-Europeans as "observers," Montesquieu critiqued, even lampooned various aspects of European society. Among the targets of the satire was the recently deceased King Louis XIV. He resigned from the Bordeaux Parlement in 1725 and, three years later, won election to the Académei Francaise. He traveled for a time, visiting Austria, Germany, Italy, and the Netherlands, and then settled in England, where he lived for two years and studied the English legal system, attending sessions of Parliament and moving in political circles, having befriended Lord Chesterfield and the dukes of Richmond and Montagu and even had an audience with the Prince of Wales. He won election to the Royal Society during his stay in England. He later wrote an account of his travels. Returning to France in 1731, he returned to writing. He anonymously published in 1734 Considerations on the Causes of the Greatness of the Romans and of their Decline, in which he argued against holding up the Roman form of government as an example in modern times.

The crowning achievement of his publishing was De l'esprit des loix (The Spirit of Laws), which appeared in 1748. Among his ideas was the separation of powers and how that theory produced a more equitable government; he discussed that form of government alongside despotism and monarchy and wrote that guiding each of the three forms of government was an overarching principle: honor (for the monarchy), fear (for the despotic regime), and virtue (for the republic). Montesquieu argued forcefully for a society and its government to have a foundation not in any character of those doing the governing–who are human and subject to whims, caprices, and harmful impulses–but, rather, in a set of laws, which exist as precepts, devoid of emotion. This book proved very influential, not only discussions involving Montesquieu and his fellow philosophes, but also in political movements that spawned governmental blueprints, such as the American Revolution and the French Revolution. A champion of individual liberty, he also argued forcefully for the abolition of slavery. Also in this work, Montesquieu espoused an anthropological theory of how climate might affect the way that people and society interact. He argued that the climate of central Europe was ideal for a society of even-tempered people because it was neither too hot (which, he said, begot "hot-tempered" people) nor too cold (which, he said, produced people with a temperament to match). Anticipating the ire of the Catholic Church, Montesquieu published La défense de L'esprit des lois (In Defense of the Spirit of Laws) in 1750. The very next year, the original work appeared on the Church's list of forbidden books. One of his last acts of writing was as a contributor to the monumental Encyclopédie that Denis Diderot was putting together. Diderot and André François le Breton had asked Montesquieu to write entries for democracy and despotism, but the famous philosopher refused, suggesting instead that he write on taste. The Encylopédie eventually included Essai sur le goût (Essay on Taste), written by Montesquieu. He suffered from failing eyesight in the last few years of his life and died of a fever in Paris on Feb. 10, 1755; he was 66.

|

|

Social Studies for Kids

copyright 2002–2026

David White