|

Why Is It That D.C. Is Where It Is? Like so much of what is in America's founding document, the Constitution, the location of Washington, D.C., was the result of a compromise. The Colonial Army had won the Revolutionary War, and the Constitutional Convention had replaced the Articles of Confederation with the Constitution, but the new government did not have a permanent home. Various cities had functioned as the capital city for a time, but colonial leaders wanted the capital to stay in one place. The question was where would it be.

By 1789, when George Washington assumed office as the first President of the United States and he had named his first Cabinet, the country was still struggling with debts incurred during the war with Great Britain. Some states, in particular, had rather large debts. Alexander Hamilton, the first Secretary of the Treasury, delivered his First Report on Public Credit in January 1790. Among the details of this report was a proposal that the federal government take on all debts currently owed by state governments. Hamilton's idea was to roll all of the outstanding state debts into one federal debt and then sell government bonds in order to pay off the debt. Those who would buy such bonds would be more likely to buy them from the newly created federal government than from a state government, Hamilton reasoned. The proposal met with opposition from first James Madison and then Thomas Jefferson. Both were from Virginia, which had already paid off its state debt. Other states had, too. Several of the states that still had debts were notably in the North. Hamilton, as leader of the Federalist Party, offered a compromise to Jefferson and Madison, leaders of the Democratic-Republican Party: approve the debt assumption plan and get a Southern national capital in return. Hamilton was from New York, whose largest city had been the most prominent location of the erstwhile national capital. By agreeing to move the national capital to a Southern state, Hamilton was giving up a certain amount of prestige for New York and for Northern states. However, Hamilton thought it much more important to have a strong federal government and for states to defer to that federal government. Jefferson and Madison, who preferred the decentralized power of state governments, did not agree with this line of thinking. The two Virginians did, however, agree to the proposal in the end because the lure of having the capital in the South proved too hard to ignore. The call went out for land on which to build the new national capital.

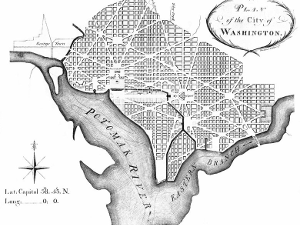

The result was the Residence Act, which gave President Washington the power to fix the boundaries of the new federal district. As it turned out, the district was to be a square measuring 10 miles on each side; on a map, the square would look like a diamond. Washington chose territory along the Potomac River–69 square miles of land from Maryland (including what was then Georgetown) and 31 square miles from Virginia (including what was then Alexandria)–and the result was the new national capital, which was named after the first President himself and would be administered by the federal government, not any state.

Washington commissioned French engineer Pierre Charles L'Enfant, who had fought in the Colonial Army, to design the new capital city. L'Enfant did just that, creating a plan that included wide avenues and open spaces. He based his design in part on other famous cities like Amsterdam, Milan, and Paris. In 1791 and 1792, surveyor Andrew Ellicott and a group of engineers, including the African-American scientist Benjamin Banneker, laid out the survey markers for the boundaries of the new federal district. (Many of these markers are still there.) When Washington dismissed L'Enfant because of creative differences and took his plans with him, Banneker reproduced the plans from memory. The city and district were built, and Congress had its first session in Washington, D.C., on Nov. 17, 1800. Have a suggestion for this feature? Email Dave. |

Social Studies for Kids |