Ulysses S. Grant: U.S. President, Civil War Victor

In March 1865, the number of Union troops in the area of Petersburg and Richmond was about 125,000. More were on the way. In the Shenandoah Valley but, having finished operations and returning, was the cavalry commander Sheridan, along with 50,000 more troops. Also soon to converge on the area was Gen. William T. Sherman at the head of another large force, the one that had taken Atlanta and gone on the "March to the Sea" and had laid waste to the Carolinas. By contrast, Lee had a force of 50,000 that still had fighting spirit but was weakened by disease and a lack of food and other supplies; as well, the desertions from the Confederate army had begun to rise. Lee devised an attack to be led by Maj. Gen. John Gordon that was to break through the Union lines. The location for this was Fort Stedman, and the attack, on March 25, succeeded for a time, punching a 1,000-foot-long hole in the Union line. However, the Union army, which had been planning an attack of its own, soon recovered and punched back with devastating force, opening up on the Petersburg defenses with every piece of heavy artillery it had. Gordon and his men, their numbers dwindled significantly, retreated.

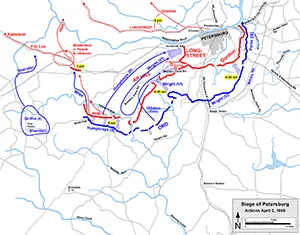

Sheridan and his cavalry had returned by the end of March, arriving from the west. Lee sent nearly 10,000 men under Maj. Gen. George Pickett to Five Forks, to protect that town and its accompanying Southside Railroad. Sheridan and his men easily won the Battle of Five Forks, on April 1. Pickett wasn't even there on the day of the battle and was relieved of his command. The following day, Grant ordered a mass assault on the Confederate line. Union troops made the kind of progress that they had hoped to make many months earlier, forcing the defenders back to the inner ring of fortifications. While riding between the lines to encourage the defenders, Confederate Gen. A.P. Hill, one of Lee's most trusted and longest-serving commanders, fell to Union bullets. Darkness stilled the guns for the day. On that same day, however, Lee had informed Confederate President Jefferson Davis and the rest of the government that he was leaving Petersburg. Evacuations were taking place even as other defending troops were fighting to protect them. The Union occupied Petersburg at dawn on April 3 and Richmond at the end of that same day. Lee was on the move, hoping to meet up with Gen. Joseph Johnston and his troops in North Carolina. Lee's men arrived at Amelia Court House on April 4; looking for food and weapons, they found only weapons. In desperation, the Confederate troops took the countryside in search of food, begging the local populace to help them. In pursuit and eventually overtaking Lee's army was Sheridan and his cavalry. The two armies clashed on April 6, at Sayler's Creek. The result was a resounding victory for the Union; losses for Lee totaled one-quarter of his army, and among those were a handful of generals. The remaining Confederates marched on, headed for Appomattox Station and what they hoped were supply trains. Arriving in the town ahead of Lee's army was another Union cavalry commander, Maj. Gen. George Armstrong Custer, who ordered his men to burn the supply trains that Lee's army so desperately needed. The Confederate army arrayed itself at the small settlement of Appomattox Court House. The Union cavalry under Sheridan, who had just arrived, blocked one approach out of town, and Grant had sent three corps of infantry on a hurried march to join Custer's cavalry. At first light on April 9, Confederate troops under Maj. Gen. John Gordon attacked the Union cavalry and, pushing back the first line, found themselves face-to-face with Union infantry. Realizing that his army was far outnumbered and effectively trapped, Lee rode out with a handful of aides to request a meeting with Grant. The two commanders traded messages for a few hours and then met at the home of Wilmer McLean. Lee, arrayed in his finest dress uniform, arrived first. Grant, who had been suffering from a severe headache, arrived in a field uniform stained with mud. The two men traded stories about the Mexican-American War, in which they had both fought, and then discussed terms of surrender. Grant offered to release all of Lee's soldiers, giving them leave to return to their homes without facing the prospect of capture or imprisonment, provided that they leave behind all of their army-issued weapons; in addition, Lee gained the addition of allowing his men to take their horses and mules with them (because unlike the Union soldiers, the Confederates owned their horses and mules and, more likely than not, needed those animals on the farms to which they were returning). Grant also told Lee that Union troops would supply their Confederate counterparts with rations for every remaining soldier. Grant discouraged his men from cheering, reminding them of the terrible cost already paid by those who had gone before them. Representatives from both parties hammered out the details of an official surrender ceremony. Next page > In the White House and Beyond > Page 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7 |

|

Social Studies for Kids

copyright 2002–2026

David White