Ulysses S. Grant: U.S. President, Civil War Victor

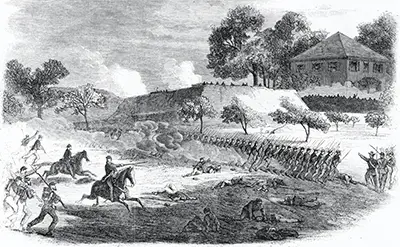

In a rare success, the Union command outfoxed the Confederate command and, on June 12, got its troops across the James River unopposed and on the road to Petersburg, erecting a 2,100-foot-long pontoon bridge to do so. On June 15, the first fighting began. At this time, most of the Confederate force was elsewhere. Defending Petersburg were a few thousand troops under the command of Gen. P.G.T. Beauregard. Attacking those troops on June 15 were 10,000 Union troops from Maj. Gen. Benjamin Butler's Army of the James, under the command of Gen. William Smith. Butler had attacked the city on June 9, before Grant and his troops began their move south, but had been repulsed. They got another chance six days later.

The fortifications at Petersburg were extensive, and the smaller defending force held off the larger attacking force, despite the latter having some temporary successes. Lee, racing back to Petersburg with the Army of Northern Virginia, arrived and began to add his troops to the city's defense, both on patrol and in building further fortifications. On June 16, the numbers were still very much in the Union's favor, with 50,000 troops ready to face off against 14,000 Confederate troops. Attacks by a force under Ambrose Burnside and Winfield Scott Hancock did little damage to the defenders and, after fierce counterattacks, were called off. By June 18, the Union force ringing Petersburg approached 67,000 men in strength. By that time, however, a number of subsequent futile attacks resulting in casualties exceeding 11,000 had convinced Grant that a full-scale assault on the city would result in nothing more than added bloodshed with no purpose. The Union soldiers dug trenches around the city and settled in for a siege. They didn't entirely surround the city, though. Grant knew that a prolonged siege would be difficult for his troops as well. He had learned that as commander of the Siege of Vicksburg in 1863. With this in mind, he had, in late June, approved a plan to dig a tunnel underneath the Confederate defenses, plant explosives, and then set them off, using the resulting distraction as cover for a fierce attack that he hoped would break through Petersburg's vaunted defensive fortifications. By the end of July, the 20-foot-deep shaft was 511 feet long and was underneath Elliott's Sailent, a fort right in the middle of the First Corps defensive line. At the end of the shaft was a large chamber that housed 8,000 pounds of explosives. The troops detonated the charges at 4:44 a.m. on July 30. The result was a resounding explosion that shattered everything in its surroundings, killing hundreds of Confederate soldiers, blowing to bits their guns and fortifications, and creating a crater that was 170 feet long, 30 feet deep, and up to 80 feet wide. What happened next came to be called the Battle of the Crater. A combination of bad planning and poor execution resulted in nothing so much as many more Union deaths, including a significant number of a group of United States Colored Troops. Skirmishes continued into September and through October, and then both sides settled in for the winter. A brief battle at Hatcher's Run in February 1865 was inconclusive. However, the winter, the lack of reliable supply lines, and the length of the siege had taken its toll on the Confederate army. |

|

Social Studies for Kids

copyright 2002–2026

David White