The Beginning of the U.S. Supreme Court

Article III of the United States Constitution calls for the establishment of a Judicial Branch of the federal government, but the specifics of a Supreme Court were spelled out in an act of Congress, the Judiciary Act of 1789. That Act provided for the highest court in the land to have six justices, of which one would be the Chief Justice. (The proper terminology is Chief Justice of the United States, not Chief Justice of the Supreme Court.)

The Supreme Court was to begin its first session on February 1, 1790. However, John Jay, the Chief Justice, couldn't make it. So, the Court first convened on February 2. Also in attendance were the five associate justices: John Blair, William Cushing, James Iredell, John Rutledge, and James Wilson. They met first in the Merchants Exchange Building in New York City and in Philadelphia and then moved

The Supreme Court was to begin its first session on February 1, 1790. However, John Jay, the Chief Justice, couldn't make it. So, the Court first convened on February 2. Also in attendance were the five associate justices: John Blair, William Cushing, James Iredell, John Rutledge, and James Wilson. They met first in the Merchants Exchange Building in New York City and in Philadelphia and then moved  to Washington, D.C. (The Judicial Branch was considered by the Founding Fathers to be much the lesser of the three Branches of Government, and no official meeting place for the Supreme Court was built until 1935. The Court met in the Capitol Building and in the Senate Chambers until then.)

to Washington, D.C. (The Judicial Branch was considered by the Founding Fathers to be much the lesser of the three Branches of Government, and no official meeting place for the Supreme Court was built until 1935. The Court met in the Capitol Building and in the Senate Chambers until then.)

The first session of the Supreme Court was extremely uneventful in terms of caseload. In fact, the Court didn't hear its first case until 1792.

One of the first cases with far-reaching consequences was Chisholm v. Georgia (1793), in which the Supreme Court decreed that citizens of one state (South Carolina) could sue another state for payment of Revolutionary War bills. U.S. Attorney General Edmund Randolph argued the case on behalf of the South Carolinians; lawyers for the state of Georgia refused to appear, claiming that they were exempt from such lawsuits. The Court, in a 4–1 opinion, disagreed. Public opinion was almost universal in shock at this first attempt by the Court to insert itself into state-versus-state disputes, and the result was the Eleventh Amendment, which among other things denied the Supreme Court such powers.

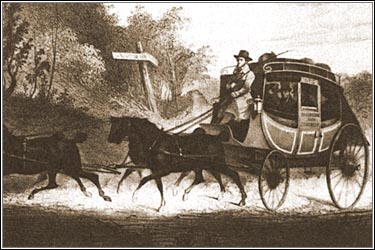

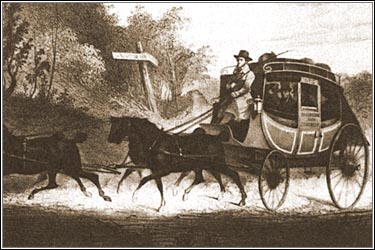

The Judiciary Act of 1789 divided the United States into 13 districts, with courts in 13 major cities, and three circuits, or appeals courts, in other parts of the country, one each in the eastern middle, and southern U.S. The Supreme Court Justices were required to "ride circuit," or travel to the various circuits and hear cases, twice each year.

The Judiciary Act of 1789 divided the United States into 13 districts, with courts in 13 major cities, and three circuits, or appeals courts, in other parts of the country, one each in the eastern middle, and southern U.S. The Supreme Court Justices were required to "ride circuit," or travel to the various circuits and hear cases, twice each year.

The power and scope of the Court's authority increased dramatically following the appointment of John Marshall to be Chief Justice. (Marshall  was actually the nation's fourth Chief Justice. Jay served from 1790 to 1795, Rutledge served for one year, and Oliver Ellsworth served from 1796 to 1801.) In a series of decisions beginning with the famous Marbury v. Madison and extending through Gibbons v. Ogden, McCulloch v. Maryland, and others, Marshall and the Court carved out a role for themselves in the lawmaking process that continues to this day.

was actually the nation's fourth Chief Justice. Jay served from 1790 to 1795, Rutledge served for one year, and Oliver Ellsworth served from 1796 to 1801.) In a series of decisions beginning with the famous Marbury v. Madison and extending through Gibbons v. Ogden, McCulloch v. Maryland, and others, Marshall and the Court carved out a role for themselves in the lawmaking process that continues to this day.

The Supreme Court was to begin its first session on February 1, 1790. However,

The Supreme Court was to begin its first session on February 1, 1790. However,  to Washington, D.C. (The Judicial Branch was considered by the Founding Fathers to be much the lesser of the three Branches of Government, and no official meeting place for the Supreme Court was built until 1935. The Court met in the Capitol Building and in the Senate Chambers until then.)

to Washington, D.C. (The Judicial Branch was considered by the Founding Fathers to be much the lesser of the three Branches of Government, and no official meeting place for the Supreme Court was built until 1935. The Court met in the Capitol Building and in the Senate Chambers until then.) The Judiciary Act of 1789 divided the United States into 13 districts, with courts in 13 major cities, and three circuits, or appeals courts, in other parts of the country, one each in the eastern middle, and southern U.S. The Supreme Court Justices were required to "ride circuit," or travel to the various circuits and hear cases, twice each year.

The Judiciary Act of 1789 divided the United States into 13 districts, with courts in 13 major cities, and three circuits, or appeals courts, in other parts of the country, one each in the eastern middle, and southern U.S. The Supreme Court Justices were required to "ride circuit," or travel to the various circuits and hear cases, twice each year. was actually the nation's fourth Chief Justice. Jay served from 1790 to 1795, Rutledge served for one year, and Oliver Ellsworth served from 1796 to 1801.) In a series of decisions beginning with the famous

was actually the nation's fourth Chief Justice. Jay served from 1790 to 1795, Rutledge served for one year, and Oliver Ellsworth served from 1796 to 1801.) In a series of decisions beginning with the famous