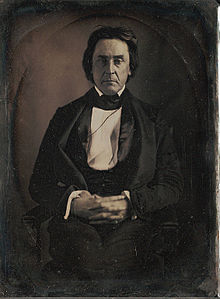

David Atchison: President for a Day?

The list of Presidents of the United States includes the name of David Atchison, according to one line of thinking that has many supporters. Atchison, so the story goes, was President for all of a day; however, he remembers his day as head of the Executive Branch no better than does anyone else. The real story involves politics, religion, and a bit of fatigue. The Election of 1848 had resulted in victory for Zachary Taylor and Millard Fillmore. That election took place in November of 1848, and Taylor and Fillmore won the most votes in the popular vote total and in the Electoral College vote. So, they were all set to become President and Vice-president on Inauguration Day in 1849. That day, as prescribed by law, was March 4. And so, at noon on March 4, 1849, James K. Polk ceased being President. Under normal circumstances, that would not have caused a problem because the next President would then be sworn in and the running of the country would go on. But March 4 in 1849 was on a Sunday. Zachary Taylor was so pious a Christian and so adamant that he would observe his religion’s practice of not working on the Sabbath, or Sunday, that he refused to show up for work that day, even to be sworn in as President of the United States. Taylor insisted on being sworn in on the following day, Monday, March 5, 1849. And so it happened: Taylor took the oath of office and officially became President, and Fillmore officially became Vice-president. But who was President when Polk’s term ended? One answer to that question is “No one.” Technically, Polk’s term had ended at noon on March 4 and no one had taken the oath of office; so technically, no one was President until Taylor assumed the position at noon the following day. So, technically, the United States was without a President for a day. Most historians would argue otherwise, saying that the incoming President was nominally in charge and that it was a technicality that Taylor hadn’t yet taken the oath of office. The country was not at war, Congress was not in session, and the President’s attention was not needed for anything on that day.

Another answer to that question is “David Atchison.” He was a Senator from Missouri who had been president pro tempore (unofficial leader) of the Senate since 1845. A law on the books dating from 1792 set down the line of succession from the President to the Vice-president, then to the president pro tempore. So, according to this law, Atchison was next in line to become President should something happen to Fillmore after something happened to Taylor. Except that nothing happened to either Taylor or Fillmore on March 4 because they did not report for duty to get sworn in to assume their offices. So, the theory goes, on this day, March 4, 1849, David Atchison was, technically, the leader of the country. Technically, the theory goes, David Atchison was President of the United States, for a day. The biographer of Atchison, William E. Parrish, argues otherwise, as do many historians and some constitutional scholars. Atchison, for his part, never insisted that he was President. Many people disagree, however, and so the story endures. Lacking proof either way, historians and non-historians are left to wonder. If Atchison were to have been officially President on that one day in 1849, he would have been the youngest President ever. He was 41 years, 6 months old on that day, younger than Theodore Roosevelt, who holds the official record for the youngest President of the United States. As for Inauguration Day falling on Sunday, it has happened since 1849 – fives times, in fact. Every one of those times, however, the incoming President has, as on any other day of the week since 1849, taken a private oath of office in advance of the public swearing-in ceremony. What of Atchison himself? He served as president pro tempore again, from 1852 to 1854, and then took part in several violent clashes in “Bleeding Kansas,” one of the results of the Kansas-Nebraska Act, of which he was a primary architect. He joined the Missouri State Guard, was made a general, and led other men into battle, including a defeat of Union troops in the Battle of Liberty, fought in September 1861. The Union victory at Pea Ridge, Arkansas, also resulted in a Union seizure of Missouri, and Atchison fled to Texas. Atchison returned to his farm after the war and died there in 1886. Atchison’s legacy continues. Named for him were a Kansas town, a Kansas county, a Missouri county, and a railroad: the Atchison, Topeka and Santa Fe Railroad. Celebrating his supposed legacy as “President for a day” is the Atchison (Kan.) County Historical Museum, in his namesake town in Kansas; the museum has an exhibit dedicated to him and his supposed presidency and claims that it is the country’s smallest presidential library. As for what Atchison did on March 4, 1849, when he was supposedly President? He slept. He said that he had spent four busy days and nights before then finishing up Senate business and spent the majority of that Sunday in March 1849 asleep. He certainly did not take the oath of office (publicly). |

|

Social Studies for Kids

copyright 2002–2026

David White