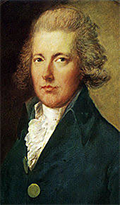

William Pitt the Younger

William Pitt the Younger was a two-time Prime Minister, first of Great Britain and then of the United Kingdom. At 24, he was the youngest ever elected to that post.

He was born on May 28, 1759. His father was the Prime Minister, William Pitt the Elder, and his mother was Hester Grenville, whose brother was former Prime Minister George Grenville. Britain at the time was fighting in the Seven Years War in Europe and in the French and Indian War in North America. In 1759, the year of young Pitt's birth, Britain enjoyed great victories in both wars. Young William had poor health for most of his life. He was taught at home by a private tutor, the Rev. Edward Wilson. William learned Latin by the time he was 7. This helped him to succeed in his father's challenge of being able to recite translations from Greek and Latin authors. These experiences developed the young Pitt's oratory skills, which would serve him well in Parliament. He went to Pembroke Hall (now College), Cambridge at age 14 and graduated three years later. One of the friends he made at university was William Wilberforce, who would be the driving force behind the abolition of slavery in Great Britain. Pitt had inherited gout, and he suffered a particularly bad attack in 1773. His doctor as a cure proscribed the consumption of a bottle of port a day. Because of the toxicity of the port, following his doctor's advice actually made Pitt worse (but slowly). As a young man, Pitt often went to Parliament, to hear speeches and debates. He enjoyed hearing his father speak, but he also learned a lot from other Members of Parliament (MPs). He was there in Parliament on April 7, 1778, when his father gave his last speech. The elder Pitt died a month later. Pitt the younger studied law, passed the bar in 1780, and joined the Western Circuit. He made his first foray into politics in that year, standing as a candidate for Cambridge University. He finished last. However, he knew that he had more than one way to gain a seat in Parliament and set about finding a benefactor. Another friend that Pitt made at university was the Duke of Rutland, whose associate Sir James Lowther controlled the "pocket borough" of Appleby. (A pocket borough was said to be "in the pocket" of a wealthy patron and went to whomever that patron wanted to represent him in Parliament.) Pitt accepted the offer and, in January 1781, took a seat in the House of Commons. He was 21. As a surprise, he was called on to give his maiden speech. Without warning or preparation, he rose and gave a masterful oration, supporting William Burke's Bill of Economical Reform. It was not the last such speech he would give in Parliament. Pitt spoke out against the war with America, known in Britain as the War of American Independence and in the United States as the Revolutionary War. The last battle in that war had been fought by the time that Pitt entered Cabinet; the Treaty of Paris that officially ended the war came in 1783. He was named Chancellor of the Exchequer in 1782 by Prime Minister Lord Shelburne. Pitt had originally aligned himself in Parliament with Charles James Fox, a powerful member of the Whig Party. Fox and King George III became implacable enemies; Pitt, having to choose sides, chose to align himself with the king. Shelburne resigned as Prime Minister in 1783 and was replaced by William Cavendish-Bentinck, who had the full support of not only Fox but also former Prime Minister Lord North. The king detested the Bentinck government and dismissed it in December, offering the job of Prime Minister instead to William Pitt. When he accepted, he became the youngest ever to serve in the post. He was 24. Pitt did not have a majority of supporters in Parliament. If all of the members of the opposition, headed up by Fox and North, voted against a bill favored by Pitt, then that bill would not pass. In order to be effective as Prime Minister, Pitt needed either the support of the opposition or his own majority. For the first few months of his administration, he had neither. In fact, Parliament in January 1784 approved a measure of no-confidence in Pitt's government. Common practice when this happened was that the Prime Minister resigned and let someone else form a new government. Pitt had the backing of the king, however, and, bucking tradition, refused to resign. As it turned out, Pitt also had the support of the House of Lords, which refused to recognize the Commons' no-confidence vote. About the same time, Pitt was riding in a coach through London when a mob attacked both the coach and Pitt. He was injured but escaped, and public opinion tilted a bit in his favor. In 1784, King George dissolved the government and called for new elections. The result was an overwhelming victory for Pitt and his supporters. During the next five years, Pitt pushed through reform after reform, eliminating corruption and doing away with inefficiency, so much so that the national budget had a rare surplus. In 1786, he employed the sinking fund to pay off the national debt. (The first Prime Minister, Robert Walpole, had done this a few decades earlier. The idea was to earmark in each year's budget an amount of money to be used exclusively to pay off a large bill, such as a public debt. Many governments were in the habit of raising money by issuing bonds, which would have to be repaid with interest. Using a sinking fund was effectively doing the opposite because no interest payment would be required.) One of the revenue schemes introduced by Pitt was Britain's first income tax. Another reform enacted in this first year of the First Pitt Administration was the India Act 1784, which centralized in London the running of the East India Company. The Governor-General, at the time Warren Hastings, got more power; the governors of Bombay and Madras got less. In addition, the king was now in charge of selecting the members of the company board.

The French Revolution began in 1789, and Great Britain looked inward while carefully watching what was happening on the Continent. In 1793, France declared war on Britain and Pitt's carefully cobbled together budget surplus went toward financing the war effort. To combat France, Britain joined the First Coalition, along with Austria, the Dutch Republic, the Holy Roman Empire, Naples, Portugal, Prussia, Sardinia, and Spain. This coalition scored a few victories against France and its allies but was overall ineffective and collapsed in 1797, leaving Britain to oppose France alone. Most of those same powers joined in the Second Coalition, formed in 1798; also joining were the Ottoman Empire and Russia. One of Pitt's rare missteps was the authorization of the capture of St. Domingue (now Haiti). The Haitian Revolution had begun in 1791. Pitt, seeking to capture the island nation and use it as a bargaining chip against France, sent large numbers of troops to put down the rebellion and restore slavery. It was a disaster. The Haitian slaves put up a spirited defense of their drive for freedom. As well, yellow fever proved especially effective at taking down British soldiers. In 1798, Pitt finally called the British force home. Also in 1798, a large number of people in Ireland, gaining inspiration from successful revolutions in American and France, revolted against British rule, seeking to set up an independent republic. A prime motivation for many of those in rebellion were a desire for Catholics to have more power and opportunities. One of the leaders of the Irish revolt was Theobald Wolfe Tone, who had some success in fighting against the British military response to the rebellion. However, the Royal Army and Royal Navy were very successful in putting down the Irish rebellion, and Tone was one of those executed in the aftermath of the fighting. Britain responded politically as well, abolishing the Irish Parliament and pursuing a course of consolidation. Pitt oversaw the Act of Union, which added Ireland to the fold and created the United Kingdom. Pitt also wanted to see enacted Catholic emancipation, which would have allowed members of the Catholic faith to hold political office. (They had been denied such for many decades.) The king was happy to be the monarch of the United Kingdom but flatly refused to endorse the Catholic proposal. Pitt chose to resign as Prime Minister.

Succeeding Pitt as leader of the government was his friend Henry Addington. Pitt absented himself from Parliament but still helped in the war effort, organizing a local group of volunteer soldiers, in anticipation of a French invasion. The Treaty of Amiens in 1801 brought peace between Britain and France, and Pitt and many others breathed sighs of relief. The fighting was on again two years later, however, and Addington found it increasingly difficult to find support in government, as the French victories piled up. He resigned in 1804, and the king asked Pitt to once again lead the government. Pitt agreed but had less support than in his first administration. Pitt, however, organized the Third Coalition to fight France. A rare highlight for this coalition came in 1805, when British Admiral Horatio Nelson led an Allied victory over France at the Battle of Trafalgar. Later that same year, French forces enjoyed an epochal victory at the Battle of Austerlitz. The wars seemed to go on and on.

Pitt was also Chancellor of the Exchequer again and put his financial savvy to good use. War was expensive, though, and the national debt soared to more than double the gross domestic product. Pitt, who struggled with bad health all his life, fell ill in early 1806 and died on January 23. He never married and had no children. He was remembered as as an able administrator, a man of high financial acumen, a strong orator, an adept politician, and a friend of King George III. |

|

Social Studies for Kids

copyright 2002–2026

David White