Vercingetorix: Chieftain of Gaul, Enemy of Rome

Vercingetorix was born about 82 B.C. His father, Celtillus, was head of the Arverni tribe and was said to have been chief of the Gauls. The boy underwent military training from an early age; tall, strong, and charismatic, he excelled at fighting and inspiring others to do the same. Many historians think that the name Vercingetorix was a title, along the lines of "Great Warrior King" or "Victor of a Hundred Battles." He was a warrior and a king and had some successes in battle.

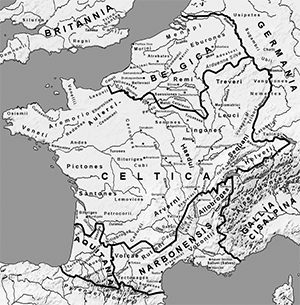

Julius Caesar was one of the three most powerful men in Rome in the mid-1st Century B.C. He and Marcus Licinius Crassus and Gnaeus Pompeius Magnus had formed the First Triumvirate in 60 B.C. and had divided up the various provinces between them. Caesar had Cisalpine Gaul and gained Transalpine Gaul after the governor of that province died.

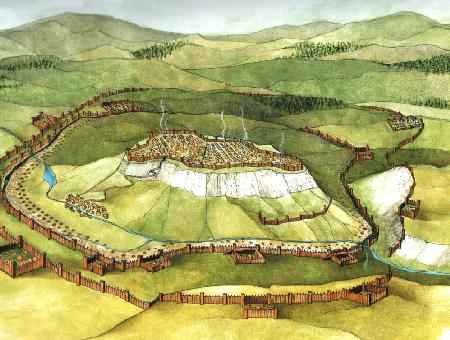

Just two years before, the Arverni had attack another Gallic tribe, the Aedui, which at the time had an alliance with Rome. The Romans were content to let Gauls fight amongst themselves at that point; but when the Helvetii, a large Germanic tribe, marched across Gaul, Caesar himself got involved. After a number of attempts at battle and keeping the peace, the two armies clashed in the Battle of Bibracte and the Romans were victorious. The Romans again intervened in Gallic fighting in 57, marching against the Belgae. That tribe, allied with the Nervii, gave the Romans great pause, but Caesar again was successful and became more involved in controlling Gaul. While Caesar and several legions were invading Britain (once each in 55 B.C. and 54 B.C.), Gallic tribes on the mainland were busy harrying Roman emplacements. Ambiorix, leader of the Eburones, led an uprising that was successful for a time. Caesar himself took charge of the Roman forces and, in 53 B.C., put down the Eburone revolt. The following year saw the rise of Vercingetorix. Caesar had returned to Rome at the end of 53 B.C. He left behind a Roman garrison, in central Gaul. The Carnutes and members of a handful of other Gallic tribes attacked during the winter, defeating the Romans at Cenabum (what is now Orleans). Vercingetorix, having by this time succeeded his father as Chieftain of the Arverni, called for a large uprising to join in battle against the Romans. As it turned out, Vercingetorix didn't have much influence as he thought he had. The elders of his tribe, including his uncle, Gobannito, quashed his calls for revolt, preferring to keep the peace with Rome, and, for good measure, exiled the young chieftain from Gergovia, the Arverni capital. The determined Vercingetorix set about gathering allies, eventually leading a coup that placed him back in control of his tribe. He also found supporters in a handful of other Gallic tribes, among them the Andi, Aulerci, Cadurci, Lemovice, Parisii, and Turoni. They targeted Roman garrisons in northern France, including an attack on the Roman ally the Boii, and made great gains. Caesar, despite the wintry conditions, crossed the Alps with an army and attacked Celtic towns in southern Gaul. (Many of the warriors of these tribes had gone north with Vercingetorix.) The Romans regained control of Cenabum and then razed it; then, they took Noviodunum. Vercingetorix called a war council, at which he and the leaders of the other tribes in the united Celtic army agreed to adopt a "scorched earth" policy: If they couldn't defend their towns and villages against the Romans, then the Romans wouldn't be able to gain from those towns and villages supplies to sustain their advance. They set 20 cities alight but spared Avaricum, choosing to defend it instead. The Roman besieged that city and, after several months, seized it. The Celts kept the Romans from seizing Gergovia, the Arverni capital, and then the Romans marched toward Lutetia (which today is Paris). Vercingetorix moved to intercept and was defeated, retreating to the walled stronghold of Alesia. The hilltop settlement would have made a daunting challenge for the Romans; but when the Celts settled in behind the strong walls and issued a call Historians for generations wrote about the siege works constructed by Caesar and the Romans at Alesia, of the towers and trenches that stretched for miles. The city was seemingly impregnable, but the Romans chose not to attack it; rather, the Romans chose to wait. The large Celtic army within the walls also had to provide for the large Celtic civilian population with the walls. The Romans had surrounded the city so completely that any reinforcements, no matter how large, could not penetrate the Roman lines and so could not get food, medicine, weapons, or other supplies into the city. Celtic warriors from within the city and from within the army outside the Roman lines attacked time and again but were unable to dislodge the Romans. At one point, Vercassivellanus, a cousin of Vercingetorix, rode at the head of a large cavalry force and succeeded in creating a gap in the Roman siege works. Vercingetorix led a large army out of the city and hit the Roman defenses at the same spot. When it looked like the Gauls were going to force their way into the Roman encampment, Caesar, watching from a nearby siege tower, stormed into the battle himself, his red cloak flying, and helped beat back the Gallic attack.

The reinforcing army, which the historian Plutarch said was 300,000, eventually abandoned their quest and left the area. Seeing no hope of continuing, Vercingetorix agreed to surrender. As the terms of this surrender, Caesar demanded all weapons in the Celtic armies' possession. He also demanded that Vercingetorix surrender himself. The proud chieftain and uniter of Gauls, wearing his finest armor, rode out to meet Caesar.

The Romans took the Gallic chieftain back to Rome and paraded him through the streets as a defeated enemy. He died there in 46 B.C., after Caesar's conquest of Gaul was complete. The Gauls did not forget the name and deeds of Vercingetorix. His story continued to be told, even as Romans and then Franks and then other conquerors ruled the once proud Gaul. In 1865, the French emperor Napoleon III ordered built a 20-foot-tall statue of the famed Gallic leader; the statue still stands on the site of the siege. Many French people today still celebrate Vercingetorix as a freedom fighter. |

|

Social Studies for Kids

copyright 2002–2026

David White

Vercingetorix was a Gallic warrior chieftain who led a spirited defense against the encroaching Roman armies in the 1st Century B.C. He scored a few hard-fought victories against Rome but eventually met defeat at the hands of Julius Caesar.

Vercingetorix was a Gallic warrior chieftain who led a spirited defense against the encroaching Roman armies in the 1st Century B.C. He scored a few hard-fought victories against Rome but eventually met defeat at the hands of Julius Caesar. for reinforcements, the Romans did their own settling in, constructing a huge series of fortifications around the city and then hunkering down to prosecute a siege. One series of walls stretched a total of 10 miles. A ditch stretching 18 feet wide was protected by a second trench, filled with water. Next was a series of buried iron "mantraps," holes in the ground that stretched several fee into the earth and contained pointed stakes that would impale anyone unlucky enough to fall in. After that was a third wall, nine feet high and populated with square towers containing siege equipment.

for reinforcements, the Romans did their own settling in, constructing a huge series of fortifications around the city and then hunkering down to prosecute a siege. One series of walls stretched a total of 10 miles. A ditch stretching 18 feet wide was protected by a second trench, filled with water. Next was a series of buried iron "mantraps," holes in the ground that stretched several fee into the earth and contained pointed stakes that would impale anyone unlucky enough to fall in. After that was a third wall, nine feet high and populated with square towers containing siege equipment.