Spain in the New World

Part 7: The End of an Empire All of that left Spain with much, much less of a presence in the New World. Santo Domingo in 1821 declared its independence but, unable to hold off occupation by Haiti, petitioned to return to the Spanish fold. The result was the resumption of colonial status, for a time. Eventually, the drive for independence surfaced again, in 1863; two years later, Spain threw up its hands and left.

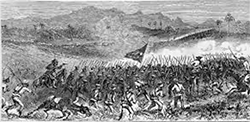

Also in the Caribbean, Cuba sought its independence multiple times, the first coming in 1868. A sugar mill owner named Carlos Manuel de Céspedes had enough money, clout, and allies to declare Cuba its own identity, daring Spain to deny the declaration of independence. Spain wasn't about to lose another possession in that part of the world and set about fighting to keep the island under its control. The conflict dragged on for ten years (giving the name to the struggle, the Ten Years' War). Those in rebellion had a manifesto and a constitutional assembly and other trappings of an independent nation, but divisions in both the military and the political apparatus stalled the momentum that the rebel forces had enjoyed. The Pact of Zanjón ended the hostilities without resolving much else. Spain certainly did not recognize an independent Cuba. Simmering resentment on the island led to a renewal of hostilities a year later, in 1879. Spain was emphatic in a victory in the Little War, ending the fighting triumphantly in 1880. In the 1890s in Cuba, a group of guerrilla fighters led by José Martí revitalized a protest movement against the Spanish-led government that had flared up a few decades before. Martí had enough support to form a U.S.-based political party, the Cuban Revolutionary Party, and to get the military struggle started. He was killed, however, early on the fighting. When the Cuban Government declared martial law in 1896, U.S. President Grover Cleveland announced that America would get involved if Spain could not resolve the crisis.

On February 15, 1898, an American ship, the USS Maine, exploded in Havana harbor, killing 266 American sailors. An initial U.S. Navy investigation concluded that the cause was an external source, presumably a mine in the harbor. Anger across America was great, and many people believed the story beginning to circulate that Spain was behind the explosion. New York newspaper publishers William Randolph Hearst and Joseph Pulitzer took the opportunity to blame Spain for the explosion and did so in print, in huge, bold headlines. The resulting swell of public opinion against Spain resulted in a movement toward support of war. About the same time, in the Pacific, the people of the Philippines were engaged in an uprising against the Spanish-influenced government there. Sentiment for the Filipino rebels, who said that they were seeking democratic rule, was high in America. Spain rejected a call from the U.S. Government to give up Cuba altogether; in response, Spain declared war. The American declaration of war followed soon after, and the struggle began.

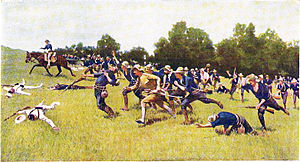

American forces landed in Cuba in late June and hooked up with Cuban rebel forces. The first battle on Cuban soil, the Battle of Las Guasimas, ended in a tactical draw, although Spanish forces left the area to shore up the defenses around Santiago. The next battles were a bit more decisive for the American effort. At El Caney and San Juan Hill, Roosevelt's "Rough Riders" and other American forces scored victories over the entrenched Spanish. American troops advanced on an even more heavily defended Santiago, where they formed into a siege strategy that eventually succeeded in the capture of Cuba's second-largest city. Meanwhile, American naval forces moved into Guantanamo Bay, where they scored a decisive victory over the Spanish Caribbean Squadron. Most American forces began to leave Cuba, however, because they had encountered an even more deadly opponent than the Spanish: yellow fever. At one point, up to three-quarters of the American occupation force had contracted the deadly disease. The island was firmly in American hands, however, and so the next orders were for evacuation, with a skeleton crew left behind. Meanwhile, in tiny Puerto Rico, the fighting was fierce as well. An initial American blockade of San Juan Bay gave U.S. forces a decided advantage, and the invasion force eventually succeeded in capturing the capital, on August 9. Three days later, Spain called for peace. A final treaty, yet another one named the Treaty of Paris, was signed on December 10. Spain gave up its New World claims to Cuba, Guam, and Puerto Rico and also handed over the Philippines. After four centuries, it was the end of Spanish occupation in the New World. |

|

Social Studies for Kids

copyright 2002–2026

David White