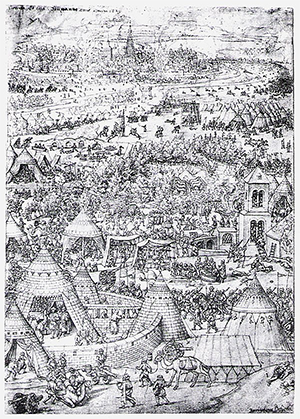

The 1529 Siege of Vienna

The 1529 Siege of Vienna was the first of several clashes of East versus West for control of the well-known Austrian city. Despite the presence of a fierce, very large siege army, the defenders prevailed.

The siege had its roots in the desire of the Ottoman Turks to move further and further into Europe. The Ottoman army under Sultan Suleiman the Magnificent (right) dealt a hammer blow to the Hungarian army under King Louis II of Hungary at the Battle of Mohács on Aug. 29, 1526. Louis died in the fighting, and the absence of an heir to his throne threw the kingdom into chaos. Emerging as the two major contenders to succeed Louis were Archduke Ferdinand I of Austria (who was married to Louis II's sister Mary) and Louis Zálpolya, a powerful noble from Transylvania, in eastern Hungary. The Ottomans claimed a part of Hungary as well, and Suleiman threw his weight behind Zápolya's claim to the throne. Ferdinand led an invasion force and seized Buda in 1527. He lost it again two years later, after an Ottoman attack, which turned into a massacre.

In the meantime, Suleiman had determined that his next target was Vienna. At the time, the seat of Habsburg power was one of the largest, richest cities in Europe. Surrounding the large, rich, powerful city were a series of high, deep walls. Nonetheless, Suleiman assembled a vary large armed force and set out to conquer. Sources vary as to the size of this armed force. One of the more commonly quoted figures is 120,000. Some sources put the number far higher. The size of that Ottoman force is significant when compared to the number of troops that were defending the walls of Vienna: 21,000. That included a set of reinforcements sent in a hurry by the soon-to-be Holy Roman Emperor, Charles V.

Suleiman's campaign began on May 10, 1529. By that time, he had assembled a very strong, very skilled fighting force filled with seasoned soldiers, archers, horsemen, and gunners. However, they had marched a long way to get to Vienna and arrived in late September after a long march through a very wet handful of weeks. By the time the army arrived, it was much depleted of manpower and resources and many of the remaining men were struggling with illness. The Ottoman cavalry turned out to be a non-factor in such a setting. As well, the army had had to leave behind many of the heavy guns, stuck in the mud. What they had managed to bring was a contingent of small cannon, which could fire cannonballs and other projectiles over the walls. Still sporting a huge advantage in numbers, the Ottomans persisted. Suleiman thought that the mere presence of such a large army featuring his vaunted janissaries encamped outside the gates and the walls of Vienna would be enough to strike enough fear into the inhabitants so that they would beg for mercy. Large numbers of people did depart the city, but the armed defenders did not. Ottoman troops set about digging tunnels under the city's high, thick walls, in order to place mines to blow up and undermine those walls. Austrian troops were well aware of such efforts and on October 6 engaged in sorties to confront such efforts, succeeding in preventing most of the mines from being detonated. That part of the battle caused heavy casualties on both sides. As well, the Austrian defense included a countermeasure against Ottoman cannon, such that the Austrians had remove the cobbles of the strees. The resulting areas of mud were more than enough to capture many objects fired by Ottoman cannons. On October 11, rain fell again, furthering dampening the spirits of men on both sides. By this time, the Ottoman supply line was virtually nonexistent and the death rate was inching up even more. Suleiman, in consultation with his war council, decided to make one final assault. This occurred on October 14 and was as unsuccessful as the previous attacks, the long pikes and accurate arquebuses of the defenders carrying the day yet again. That defeat taken, Suleiman ordered a retreat. In the main, the beleagured defenders did not emerge from behind their walls to harry the retreat. The exception was a contingent of horsemen, who rode out to take as many prisoners as they could. The departing Ottomans struggled anew, through snow this time, and finally reached Constantinople on December 16, by which time their numbers and strength were well and truly sapped. Estimates are that the Ottoman army lost as many as 15,000 men during the siege and that losses during the trip home were far higher. Meanwhile, the Austrian defenders set about repairing their city and its walls, believing that another attack was imminent. |

|

Social Studies for Kids

copyright 2002–2026

David White