Pre-Roman Spain

People have been living in what is now Spain for a very, very long time. Archaeologists have found cave art, stone tombs, and other evidence of human habitation that are tens of thousands of years old. Among the first evidence of settlement by another well-known ancient culture is that of Gadir, a colony founded by the Phoenicians. Gadir later became Cádiz. It was the Phoenicians, through their Punic language, who named España, terming it after Isephanim, the island of rabbits, otherwise known as Andalucía.

Also settling in the area were Celts, who populated much of Europe. Celtic peoples also settled notably in Britain and France, where they were known to the Romans as Gauls. In Spain, the Celts were known as the Galatians and settled in Asturias and Galicia. As well came the Greeks, arriving in the 9th Century B.C. They settled on the eastern Mediterranean coast and left behind the name of the peninsula, Iberian, after the River Iber, more well-known as the Ebro. The Greeks also applied the term Iberians to a set of peoples who were already living in the southeast when the Greeks arrived. The powerhouse Carthaginians arrived in the 7th Century B.C., eventually setting up Qart Hadasht (New Carthage) as their headquarters and convincing the Greeks to abandon their settlements.

The most well-known Mediterranean powerhouse, Rome, was in its infancy at this time. It didn't take long for Roman traders and then settlers to arrive in Iberia, invading from the south, defeating the settlers there, and founding the town of Itálica. Carthage and Rome fought three wars for supremacy in the region. After the Roman victory in the First Punic War, the Carthaginian general Hamilcar Barca determined to make Spain a Phoenician citadel. He did so, and his son-in-law, Hasdrubal, carried on the policy and work when Hamilcar died. One Greek settlement that remained was Saguntum, south of the River Ebro. Hasdrubal and Rome agreed to a treaty the terms of which included an agreement by both sides to keep Saguntum independent; further, Carthage was to keep its settlers and its troops south of the river. The death of Hamilcar also brought to power his son, Hannibal, who was bent on avenging Carthage's defeat in the First Punic War. His sudden attack on Saguntum in 219 convinced Rome to go to war again. Rome's success in the First Punic War was due in large part to its overwhelming manpower and, surprisingly, its ingenuity, specifically the invention of the corvus, which helped them turn naval battles into land battles, fights that Rome could win. This time around, in the Second Punic War, the odds were stacked again in Rome's favor in that seapower between the two civilizations was about equal, meaning that Rome had neutralized Carthage's former advantage; further, Roman advances of late had included some improvements on earlier fighting ships, meaning that Rome had actually pulled ahead of Carthage, both in technology and in manpower. Roman ships now outnumbered Carthaginian ships. Hannibal the Rome-hater would have to find another way to take the fight to the enemy.

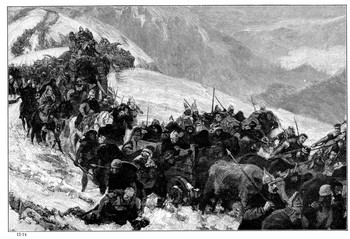

That is exactly what he did. In a master stroke of military strategy that was as unconventional as it was daring, Hannibal made the courageous and outrageous decision to cross the mighty Alps with his invasion force, choosing to attack Rome by land rather than by sea. He massed an army of 60,000 in Spain, crossed the Pyrenees, and then set out across Gaul. Hannibal made it to Italy but, after ravaging a succession of Roman legions, couldn't find enough allies to conquer Rome. The result of the Second Punic War was the same as the first, with Hannibal escaping death by fleeing Carthage. Roman troops also stormed Carthaginian positions in Spain, forcing a collapse there as well. (The Roman general Scipio had started the ball rolling in 209 B.C., taking Qart Hadasht and renaming it Carthago Nova. The Roman victory at Ilipa three years later ended Carthaginian influence on the peninsula.) As Carthage's star faded, Rome's influence took over. By 19 B.C., Rome had taken control of Spain.

|

|

Social Studies for Kids

copyright 2002–2026

David White