The Peasants' Revolt of 1381

The Peasants' Revolt of 1381 was a widespread uprising against economic uncertainty that resulted in a handful of deaths. It involved not only poor people but also people of the aristocracy, and so many historians prefer to call it the Great Revolt of 1381. England and France were technically at war, the Hundred Years War. Nearly all of the fighting took place on the Continent. Keeping the English armies fed and equipped was costing more and more money the longer the war went on. By 1381, the war was in its fifth decade.

The Black Death had devastated England and the rest of Europe for the better part of a decade, from 1347 to 1353. Deaths in London and other cities were higher than in the surrounding countryside because the plague that caused the devastation spread more quickly in densely populated areas. At the same time, the plague did not discriminate by class. Many jobs went unfilled, and many people ended up with responsibilities that they might not otherwise have had. In particular, many manor lords found it necessary to start paying the peasants who lived on the manor land, in both money and land. Some peasants, knowing that they were likely to be the only source of labor that their lord would be able to utilize, demanded higher wages before they would do the work; in many cases, the lord was forced to pay the higher demand. As the number of plague-free years grew, many of the people who had newfound privileges began to suspect that the manor lords would revoke those privileges. At the same time, Parliament had passed the Statue of Labourers, in 1351, which effectively froze wage levels, preventing peasants from inflating their wage demands. Peasants had cited rising wages as a result of the Black Death as a primary reason for their need to ask for more money.

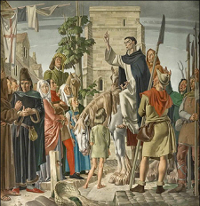

As well, many peasants worked on land owned by the church, one or two days a week, and so were not free to work on the land that they had been given; as a result, many of these peasants struggled to make ends meet. One of the Peasants' Revolt leaders was John Ball, a priest from Kent. Ball was known for his support of equality and thought that the feudal system was immoral. One of the things that he famous said was this: "If God willed that there should be serfs, he would have said so at the beginning in the world." Ball supported the peasants' desire to rid themselves of the requirement to work on church land.  The economic trigger of the Peasants' Revolt was a new poll tax, introduced by King Richard II in 1380. Everyone who was on the tax register was required to pay 5 pence. This was a good amount of money for most people at the time. In addition, it was the third such tax introduced in the past four years. Tax collectors were willing to accept something other than money, as long as it could help the war effort; but people still had to pay the tax. These three new taxes also departed from previous practice in that it required peasants, as well as landowners, to pay the tax. The 1377 tax, spearheaded by John of Gaunt, Richard's uncle who was nominally in charge of the government, was meant to be a onetime affair; the government liked the idea so much, however, that it implemented a similar tax twice more. In 1380, one by one, people refused to pay the tax. In those days, tax collectors would go to people's homes in order to collect such taxes. People who didn't pay taxes usually incurred fines and other penalties. Tax collectors sometimes had armed escorts, but this wasn't entirely common practice.

One flashpoint in May 1381 was the Essex village of Fobbing. The Royal Council had counted all of the money collected so far and found that it wasn't as much as it should have been. The council decreed that tax collectors go out again and collect more tax. A tax collector named Thomas Bampton, accompanied by a few other men, went to the village in order to collect. They summoned the local villagers and those who lived in the nearby villages of Corningham and Stanford and told them they would have to pay more tax, not only for themselves but also for the residents of all three villages who hadn't answered the summons. The residents of Fobbing responded violently, beating Bampton and his men and otherwise convincing them to leave. The next month, a chief justice, Sir Robert Belknap, tried to succeed where Bampton had failed; the result was the same. Fobbing wasn't the only such locality. Many people from many villages and towns got together and marched on London, wanting to deliver their complaints about the new tax to King Richard II in person. Acts of violence accompanied the march toward London. The marchers turned their ire toward landowners, burning manor houses. Some people destroyed tax records; others burned down buildings in which government records were stored. More and more people joined in the revolt, and the acts of violence spread. Some people died in the violence. A man named Wat Tyler emerged as a leader of the revolt, along with Ball. Not much is known of Tyler's life before he joined the uprising. Once the mob had reached London, Richard approached them personally. This meeting took place on June 14 at Mile End. Richard agreed to all of the peasants' demands, on the condition that they return to their homes. Some of them did. Others did not, preferring to continue the violence. Among their targets were Lord Chancellor and Archbishop of Canterbury Simon Sudbury and Lord High Treasurer Robert Hales, both of whom were killed.

The next day, Richard rode outside the city walls, to Smithfield, to again meet with the peasants. The king again promised to meet all of the peasants' demands and vowed that they would have safe passage home. At some point, the Lord Mayor of London was convinced that Wat Tyler was about to kill the king and so stabbed Tyler, who died. The crowd dispersed. Richard withdrew the poll tax but later claimed that his promise of subsequent safety was made under duress and ordered some of the leaders of the revolt, including Ball, killed. |

|

Social Studies for Kids

copyright 2002–2026

David White