Johan Gutenberg: Inventor of Modern Printing

Johan Gutenberg grew up in relatively obscurity in medieval Germany, but his invention of movable type revolutionized the world of communication and his name and his invention live on in worldwide fame.

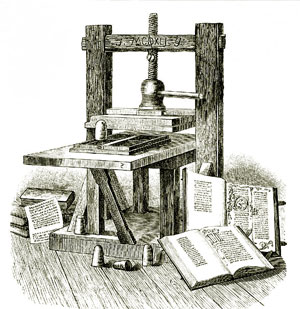

The rest of Johan's early life is largely unknown as well. He is known to have lived in other cities in Germany, including Strasbourg for a time. Historians know for certain that he was back in his hometown of Mainz in 1448 and that by 1450, he had put into operation a prototype of the printing press that would make him famous. One of the first works to be printed was a German poem. After obtaining a loan from a moneylender named Johann Fust, Gutenberg began building his invention in earnest, at a workshop on a property in Hof Humbrecht, helped by a man named Peter Schoffer. Some historians think that Schoffer, who had worked as a scribe in Paris, designed some of the first typefaces. The workshop is thought to have employed up to 25 people at one time. In 1455, the 42-line Bible, which has come to be known as the Gutenberg Bible, was printed. The Bible was in two 300-page volumes. The pages had 42 lines, and some pages were enhanced with hand-drawn illustrations after printing. At first, 180 copies were made, most of them on paper, although some were printed on vellum, a kind of parchment. Gutenberg's press was also printing other texts as well, including church publications and Latin grammar books.

Gutenberg's genius was in perfecting a means of printing by movable type. Past printing methods had relied on painstakingly hand-driven activities, such as copying longhand, carving type into wooden blocks a character at a time, and drawing on one parchment at a time. Gutenberg's printing press changed all that by incorporating metal representations of letters, numbers, and punctuation marks that could be moved relatively easily from one position to another, speeding up the printing process. He also invented oil-based ink, which meshed better with the metal used to print the type. However, because of his dispute with Fust, he toiled in relative obscurity for much of his life. In 1465, when he was getting on in years, he was given the title of Hofmann, or "gentleman of court." This title brought with it an annual income of money and food, but it wasn't very much in the end. Johan Gutenberg died in 1468. He was buried in a church cemetery in Mainz. Both church and cemetery were later destroyed, and so Gutenberg's final resting place is unknown. He is famous, though. Many statues of him stand in Germany. Many buildings, including entire universities, are named after him. A huge online library (Project Gutenberg) is named for him. An asteroid, 777 Gutemberga, is named for him. More widely, his invention is thought by many historians to have helped pave the way for the Reformation and the Scientific Revolution, by making books more easily produced, obtained, and afforded. |

|

Social Studies for Kids

copyright 2002–2026

David White

Born in Mainz, Johan was the son of a merchant. Historians don't agree on exactly when Johan was born (although the general belief is sometime around the beginning of the 15th Century), but they do agree that his family was in the upper class. Some reports say that his father, Friele, was a goldsmith for the Mainz bishop. He obviously had some knowledge of the trade because he passed on that knowledge to Johan.

Born in Mainz, Johan was the son of a merchant. Historians don't agree on exactly when Johan was born (although the general belief is sometime around the beginning of the 15th Century), but they do agree that his family was in the upper class. Some reports say that his father, Friele, was a goldsmith for the Mainz bishop. He obviously had some knowledge of the trade because he passed on that knowledge to Johan. The following year, Fust won a lawsuit against Gutenberg, which resulted in Fust's taking over Gutenberg's workshop and a large number of undistributed Bibles. The resourceful Gutenberg, however, found backing from somewhere else and moved his shop to nearby Bamberg and continued his work. Gutenberg is thought to have printed another large work, the Catholicon dictionary, which ran to 754 pages, and several other smaller books.

The following year, Fust won a lawsuit against Gutenberg, which resulted in Fust's taking over Gutenberg's workshop and a large number of undistributed Bibles. The resourceful Gutenberg, however, found backing from somewhere else and moved his shop to nearby Bamberg and continued his work. Gutenberg is thought to have printed another large work, the Catholicon dictionary, which ran to 754 pages, and several other smaller books.