Chartism in the United Kingdom

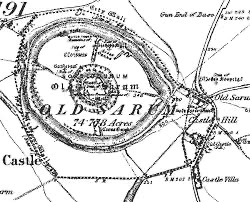

Chartism was a drive for more political representation for the working classes in the United Kingdom in the 19th Century.  The Reform Act 1832 had added more than 200,000 to the voters rolls while doing away with "rotten boroughs." However, it was still only 1 in 7 adult males who could vote after the passage of this bill. Many in the working classes wanted more. The Reform Act 1832 had added more than 200,000 to the voters rolls while doing away with "rotten boroughs." However, it was still only 1 in 7 adult males who could vote after the passage of this bill. Many in the working classes wanted more.

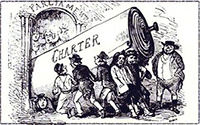

The Chartist movement began in the 1830s and had large numbers of activists and a large amount of recognition for about a decade. What the Chartists really wanted was for more people to have political rights and influence. The movement had adherents in all four elements of the U.K.–England, Ireland, Scotland, and Wales.  The name of the movement came from the People's Charter, which listed the six main aims of the Chartist movement:

Many in the Chartist movement, such as Collins and Lovett, preferred to work within the system, to gather large numbers of signatures for a petition to Parliament and try to win over MPs with their words moreso than their actions. Some, such O'Connor, favored a more physical approach. They advocated the use of hostile language and encouraged violent behavior. Some people even talked of taking up arms to support their street protests against what they saw as political disenfranchisement. Riots in Birmingham and Newport killed several people, injured many more, and resulted in the imprisonment of still more. During one particular large and loud protest, Queen Victoria left London for the Isle of Wight and the Duke of Wellington and thousands of soldiers were dispatched in the streets to keep the peace.

Leaders of the movement tried three different times to petition Parliament to address their concerns, in 1839, 1842, and 1848. Parliament, ignoring the fact that millions of people had signed each petition, rejected the Charter all three times. It didn't help that O'Connor, who had been elected to Parliament in 1847, had claimed that the 1848 petition contained more than 6 million signatures. Many of these were found to be duplicates or outright fakes. Those in Parliament tasked with verifying the signatures discovered the alleged signature of Queen Victoria herself. Preceding the presentation to Parliament of the third and final petition was a Chartist meeting on Kennington Common that authorities say was attended by 150,000 people. The third rejection of the People's Charter convinced the leaders of the movement that their efforts were not going to be successful. Their activism led to later success, however, as the Reform Acts of 1867 and 1884 included elements of the Charter. |

|

Social Studies for Kids

copyright 2002–2026

David White