The War of the Third Coalition

Part 2: French Victory in Germany; U.K. Victory at Sea

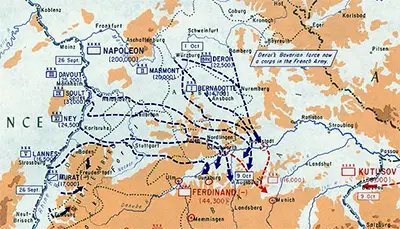

Feldmarschall-Leutnant Karl Mack of Austria had a plan to concentrate forces near Augsburg, on the Lech River. After a large amount of his troops had occupied Munich, Mack changed the plan. This had a cascading effect of miscommunication that was worsened by increasingly bad weather. France had achieved the advantage of surprise in part, crossing the Danube as well, and also had twice as many troops, and this led to a quick victory at Wertingen. Austrian forces were too slow to react and, consequently, unable to organize a proper retreat. The October 8 battle ended with almost the entire Austrian force of 5,000 lost. Marshals Joachim Murat and Jean Lannes had scored a quick initial victory. That victory at Wertingen was due in part to Mack's decision to send only a small force to confront Murat and Lannes. The very next day, another battle, at Günzburg, resulted in nearly as many Austrian casualties, with French losses only one third as high. A further engagement two days later at Haslach-Jungingen was inconclusive in terms of victory or defeat, but the results was a technical defeat for Austria because its forces were not able to break away from what was quickly becoming a French encirclement. Mack himself was wounded in the fighting and, the next day, issued a series of conflicting orders that resulted in a sharp victory for Marshal Michel Ney and France at Elchingen, on October 14.

As a result, Austrian forces concentrated themselves at the fortress of Ulm, where they were surrounded by Napoleon's army. It took only a few more days for Mack to issue an order of surrender, handing over the freedom of 25,000 soldiers, 18 generals, and 65 guns. Mack surrendered himself to Bonaparte, and the victory was complete. In two weeks, the French Army had confronted an army 60,000-strong and had induced it to surrender. The battles had been fierce but small overall in number, as were French losses. While Napoleon was accepting the surrender of the Austrian army, the French and Spanish navies were fighting against the U.K. Royal Navy in the Battle of Trafalgar. U.K. Vice-Admiral Horatio Nelson (right), who had shadowed Admiral Pierre de Villeneuve's fleet through the Atlantic after first assuming that it was had headed back to Egypt and then been blown off course by a sudden storm, had been on shore leave when he heard that the Franco-Spanish fleet was massing in Cádiz. A large number of ships from the Royal Navy under the command of Vice-Admiral Robert Calder were already en route; these ships had been the ones to go into battle against the Villeneuve's returning ships. Calder's ships reached Cádiz on September 15, and Nelson arrived 13 days later. By October 15, Nelson's fleet numbered 27 ships of the line and 33 supporting ships; Villeneuve had 33 ships of the line, including one that had 130 guns, and 40 supporting ships. For a battle plan, Nelson abandoned the traditional naval line of attack and directed his ships to divide the enemy force into three, attacking head-on at a very fast speed. This unorthodox approach allowed the U.K. ships to minimize the time that the Franco-Spanish ships would have to fire on their attackers. Nelson knew that his forces were experienced and well trained and that the reverse was true for the Franco-Spanish forces. Still, Villeneuve's ships had more men at his disposal–25,000 to 17,000–and plenty of firepower.

As planned, the U.K. ships formed two columns and struck at the heart of the enemy ships. Nelson observed the scene and issued orders from his flagship, Victory, while Villeneuve, from his flagship, Bucentaure did the same. The fighting was fierce and went on for five hours. Victory was so successful at engaging the French and Spanish ships that it got close enough to the French ships Redoutable to be boarded. It was then that a French sniper felled Nelson. Another of Nelson's ships, Temeraire, entered the fray and forced Redoutable to retreat and, not long afterward, surrender. Nelson's fleet sunk or captured 22 of Villeneuve's ships (including Bucentaure) and lost none itself. Casualties on Nelson's side numbered 1,500; the 458 dead included Nelson himself, who died not long before the battle ended. French and Spanish losses were much higher: 4,700 dead, 2,500 injured, and several thousand captured. Next page > Final Battle and Peace > Page 1, 2, 3 |

|

Social Studies for Kids

copyright 2002–2026

David White

The target of French ire before had been Italy. It was not so this time. A considerable force did advance to Naples, and an even larger force remained in Boulogne, to guard against an invasion by U.K. troops. However, most of the rest of the Grand Armée streamed across the Rhine along a 160-mile front to engage Austrian troops in Germany. This began in late September 1805.

The target of French ire before had been Italy. It was not so this time. A considerable force did advance to Naples, and an even larger force remained in Boulogne, to guard against an invasion by U.K. troops. However, most of the rest of the Grand Armée streamed across the Rhine along a 160-mile front to engage Austrian troops in Germany. This began in late September 1805.