The Hundred Days: Napoleon's Return

The Hundred Days was a term used to describe the brief return to power of Napoleon Bonaparte during the latter part of the Napoleonic Wars. It occurred in 1814–1815. Bonaparte had arrived on Elba on May 14, 1814, a little more than a month after he had abdicated the French imperial throne. While in exile, he kept abreast of the goings-on in Europe. He knew that France again had a king, Louis XVIII. He knew that the leaders of Europe were negotiating at the Congress of Vienna. He didn't like what he found out. As time went on, the alliance that had coalesced into resistance to the French Empire in the person of Napoleon fragmented, as competing desires led to differences of opinion in how to carry on with relation to one another. The remaining powers disagreed on how to proceed with regard to Poland and with Saxony and other German states. Austria wanted northern Italy. The strength of Russia scared and intimidated rulers in Western Europe. Closer to home, the people of France were not all that happy with another king (even though they had had an emperor serving over them for a few years). Also filtering through On Feb. 25, 1815, a flotilla of six ships sailed from Elba. On one of those ships, the Inconstant, was Bonaparte, along with a group of loyal soldiers who had been with him on the island. They reached France on March 1. Bonaparte and his small force, which was small only in relative terms and was in reality about 1,000, put ashore near Cannes and marched toward Paris. The path was a relatively straight one, with the exception of Provence (still strongly loyal to the royalist faction), which Bonaparte and his men avoided by going through the Alps. The march to Paris was not uneventful. The path through the Alps was a difficult one, as always. As well, even though the group of King Louis XVIII had left Paris on March 13, and Bonaparte and his men arrived the following week. They had faced not a single shot fired in anger. By that time, the Congress of Vienna had declared Napoleon an outlaw. On March 25, a familiar group of countries signed the Treaty of Alliance; following that was the War of the Seventh Coalition. Bonaparte resumed his position as emperor and, on April 23, set up a new two-house parliament, the lower chamber of which (the Chamber of Representatives) had 300 elected deputies and the higher of which (the Chamber of Peers) contained members appointed by the emperor. A plebiscite approved a new constitution on May 25, and the parliament opened on June 1.

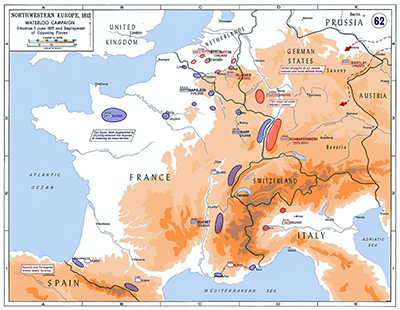

In the Treaty of Alliance, the signatories (Austria, Prussia, Russia, and the U.K.) had pledged to each contribute 150,000 men to opposing Bonaparte and France. France had nowhere near that many soldiers. The Allies had set a date of July 1 for an invasion of France. The gap between the declaration of war and the first major Allied action was to give Austria and Russia enough time to mobilize their forces sufficiently. As well, a large part of the U.K. force had been sent to North America, to fight in the War of 1812. Bonaparte chose not to wait, attacking the Prussian force at Ligny on June 16 while Ney engaged the U.K. forces at Quatre Bas. The former was a French victory; the latter was nondecisive. The Allied force at Quatre Bas withdrew to Waterloo, in what is now Belgium. The commander of that force was Arthur Wellesley, known as the Duke of Wellington. The Battle of Waterloo, on June 18, was a triumphant victory for the Allied forces and a catastrophic defeat for France. Unbowed, Bonaparte hurried back to Paris, in an attempt to assume dictatorial powers on the model of Ancient Rome. After Allied armies entered Paris on July 7, having fought their way through a few contingents of French troops on their way there. The following day, Louis XVIII returned and again took the throne. Bonaparte, meanwhile, surrendered himself, on July 15, and was sent to the U.K. (He was later sent for a second exile to St. Helena, an even more remote island than Elba. He died there in May 1821.) The powers of Europe hammered out yet another agreement, yet another Treaty of Paris, signed on Nov. 20, 1815. That agreement confirmed the Final Act of the Congress of Vienna, itself completed on June 9. This second consecutive Treaty of Paris required France:

|

|

Social Studies for Kids

copyright 2002–2025

David White

were reports of the new French government's treating the people poorly. All of this was known to Napoleon, and knowing all of this, coupled with his desire to still make a difference in the world, compelled him to escape his island exile.

were reports of the new French government's treating the people poorly. All of this was known to Napoleon, and knowing all of this, coupled with his desire to still make a difference in the world, compelled him to escape his island exile. soldiers marching toward Paris grew steadily as it went, the response from various regiments was not always favorable. On March 7, at Grenoble, the 5th Infantry stood opposed to the returned emperor and his renewed retinue. Seeing this, Bonaparte opened his coat and calmly said, "If any of you will shoot his Emperor, here I am." No soldier fired a gun or in any other way attacked Bonaparte. Instead, ending the intervening silence was the cheer "Long live the emperor!" As well,

soldiers marching toward Paris grew steadily as it went, the response from various regiments was not always favorable. On March 7, at Grenoble, the 5th Infantry stood opposed to the returned emperor and his renewed retinue. Seeing this, Bonaparte opened his coat and calmly said, "If any of you will shoot his Emperor, here I am." No soldier fired a gun or in any other way attacked Bonaparte. Instead, ending the intervening silence was the cheer "Long live the emperor!" As well,