The French Constitution of Year Ⅷ

The Constitution of Year Ⅷ, established in 1799, was France's fourth governmental blueprint in nine years. This latest Constitution established the Consulate. At the time, France was again fighting against other European powers, this time in the War of the Second Coalition. France had won the first such war, which ended with a peace agreement with Austria in 1797. Since then, however, French forces had suffered a significant naval defeat to Britain at the Battle of the Nile in 1798, and that had played a part in convincing Austria and Russia to join Britain and Turkey in going to war against France.

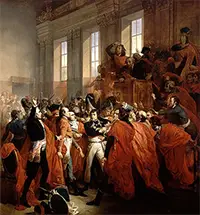

The end of the Directory came in 1799, as the result of the Coup of 18 Brumaire. Emmanuel-Joseph Sieyès (right), a leader of the Revolution from as far back as the late 1780s, won election to the Directory. He then overthrew the government, although things didn't go exactly as planned. The plan was to initiate a takeover by devious means, by inventing a conspiracy and then tricking the government into handing over the reins in time of crisis. Helping execute the plan were to be Joseph Fouché, the Minister of Police; Pierre François Réal, the Commissioner of the Directory; Charles-Maurice de Talleyrand; and Lucien Bonaparte, who was a brother of Napoleon and who was also the head of the Council of Five Hundred. The plan was for three of the five Directors to suddenly resign, leaving the government with no functioning executive arm. Then, the Councils would hear of an alleged conspiracy that necessitated the movement of the deputies to a safe location a few miles outside Paris. Because it would be a time of war, since the republic was threatened from within, the Councils would be dissolved and a handful of its deputies would set about writing a new Constitution. This was a pattern that had been followed in recent years. The coup plotters brought the army in on the deal, and Fouché was to ensure that the police did their part. Also playing a part would be Napoleon himself, by this time a war hero with several well-known victories under his belt.

On November 9, deputies in the Council of Ancients heard of the alleged conspiracy at an emergency meeting, at which they agreed to meet the following day at the Château de Saint-Cloud. They also assented to allowing Napoleon to assume command of troops in Paris. A few hours later, the same set of events occurred at a meeting of the Council of Five Hundred, with the same result. Troops then arrested two prominent Jacobin directors, in keeping with the story that it was a Jacobin plot to take over the government. The following day, the Councils met separately, with Napoleon speaking to each group. The Council of Ancient offered no opposition. The Council of Five Hundred did, but only for a time, in the form of harsh verbal resistance from a handful of Jacobin deputies. In the end, after soldiers had intervened and removed the agitators, the lower chamber reconvened and approved the formation of a new government. This was the Constitution of Year Ⅷ. (It was so named in accordance with the Republican Calendar, which had set 1793 as Year Ⅰ.)

The legislature in this new government, termed the Consulate, was three houses, a Senate (whose members served for life), a Tribunate, and a Legislative Body; membership of the three was 80, 100, and 300, respectively. The Tribunate and Legislative Body were to meet in public; the Senate meetings could not be public. Heading the government were three Consuls, the First of whom held most of the reins of government. Notably, this Constitution did not contain a Declaration of Rights.

The Constitution actually named the first three consuls: "The constitution appoints as First Consul, Citizen Bonaparte, former provisional consul; as Second Consul, Citizen [Jean Jacques Régis de] Cambacérès, former minister of justice: and as Third Consul, Citizen [Charles-François] Lebrun, former member of the commission of the Council of Ancients." However, the Constitution also made clear who of those three had the most power: "The First Consul promulgates the laws; he appoints and dismisses at will the members of the Council of State, the ministers, the ambassadors and other foreign agents of high rank, the officers of the army and navy, the members of the local administrations, and the commissioners of the government before the tribunals. He appoints all criminal and civil judges other than the justices of the peace and the judges of cassation, without power to remove them." The Constitution delineated a judiciary, consisting of justices of the peace, who served three-year terms, and judges, who served for life. In practice, the Consuls, as the executive branch, ran the government. The First Consul was the one "who promulgates the laws." The Tribunate could debate proposed laws but could not vote on them. The particulars of those debates accompanied a proposed law to the Legislative Body, which could pass or vote down laws but could not discuss or change them. The Senate reviewed draft bills in order to inform the First Consul fully on the potential results of such laws. It was up the First Consul, then, to declare proposed laws in effect or dead letters. The Consulate came into being after a nationwide vote, on Feb. 7, 1800. The response was overwhelmingly in favor of the new Constitution.

|

|

Social Studies for Kids

copyright 2002–2026

David White