King Edward II of England

Part 2: King in His Own Right Among the new king's first actions were to call off the Scottish attack and to recall Gaveston from exile. (The new) King Edward made Gaveston Earl of Cornwall, a position of nobility, and arranged for him to marry a wealthy woman, Margaret de Clare. Edward also had the royal treasurer removed from his post and then arrested.

In 1308, Edward proceeded with the planned marriage to Isabella, the 12-year-old daughter of the King of France. Edward went to France to negotiate with Philip and left Gaveston in charge of England as regent. Edward's nobles frowned on this second elevation of a man not of English birth being given great responsibility. Edward and Isabella were married in Boulogne on January 25. They returned to England and enjoyed a lavish coronation and wedding feast. Gaveston had a major role in those events as well. Edward found himself defending his relationship with Gaveston at meetings of Parliament in early 1308. Under threat from his barons, who had the support of France's King Philip, Edward agreed to exile Gaveston to France, at the last moment changing his mind and sending him to Ireland, as Lieutenant of Ireland. After a series of negotiations with the barons and with Church officials, Edward succeeded in bringing Gaveston back to court, in exchange for reducing some of the power of the royal household. Gaveston once again alienated many of the barons, and some, including the powerful and important Earl of Lancaster, refused to attend Parliament in 1310 as long Gaveston was there. Edward, meanwhile, was seeking money in order to pay for a fresh war on Scotland and to eliminate his debts to banks in Italy. (His father had left him with a sizable debt, and Edward had added to it.) When Parliament finally did meet, Edward bowed to pressure from the barons and agreed to a proposed set of reforms that included replacing Gaveston as the king's chief advisor with a council of 21 barons. The barons set about finalizing the terms of the agreement, and Edward took Gaveston and an army of nearly 5,000 and headed north. This campaign didn't achieve much and had to be abandoned when the money to finance it dried up. Edward and the army headed south. In October, he agreed to the Ordinances of 1311, which gave Parliament the right to approve the king's petitions to go to war and to hand out land. Also according to the terms of the Ordinances, Gaveston was exiled again.

Edward tired of the restrictions of his barons and revoked the Ordinances. He further provoked the barons by recalling Gaveston yet again. The response from the barons and the Church was fast and furious. The Archbishop of Canterbury excommunicated Gaveston, and an army put together by the Earl of Lancaster and others who supported him pursued a fleeing Edward and Gaveston. The two parted, and Gaveston was captured. He was tried for treason and found guilty of violating the terms of the Ordinances, which had stated that he was to be exiled once and for all. He was executed on June 19, 1312. Edward was furious, but he had lost valuable support by this time. The Earl of Lancaster, who happened to be Edward's cousin, had a considerable number of barons on his side, not to mention a large army. Edward did still have a royal army, and the two sides narrowly avoided civil war by agreeing to a truce, out of which Edward agreed to pardon the barons who had killed Gaveston and the barons agreed to pay for a new campaign in Scotland. Also at this time, Edward cemented his relationship with King Philip of France. Edward now had the nominal support of the barons and a new allotment of money with which to finance an invasion of Scotland.

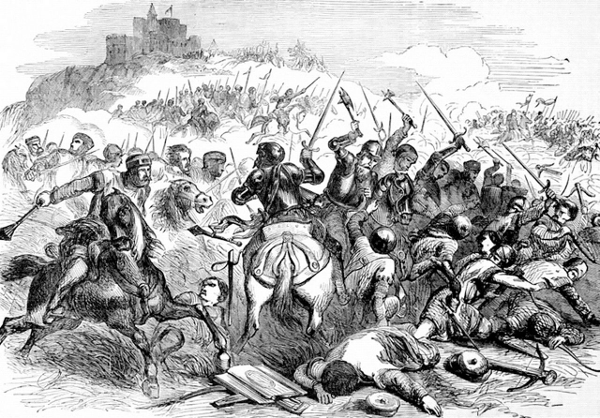

Robert the Bruce had not been idle. By 1314, he had retaken most of the castles in Scotland that King Edward I had once controlled. Scottish raiding parties roamed northern England. Edward amassed an army every bit as big as the kind that his father used to command and marched north. He hastened the pace when he received word that Scottish forces were about to take Stirling Castle. Historians generally agree that the Scottish forces were at the most half of the English forces on June 23 at the Battle of Bannockburn. Yet, Robert the Bruce and the Scottish forces won the day, ambushing a surprised Edward and his English forces, carrying on with what turned into a massacre, and nearly killing Edward himself. Edward had turned a well financed expedition that by rights should have resulted in a victory into a humiliating defeat. Edward, his political capital again at an ebb, suffered further anguish when the Great Famine engulfed northern Europe. A combination of heavy rains, a cold winter, and then more heavy rain in 1314 brought on a period of several years in which harvests suffered and prices of food and other goods rose. Starving commoners revolted in Bristol, London, and Lancashire. The discontent lasted for a few years. At the same time, Lancaster and other barons were refusing to attend Parliament. Yet another truce resulted in a 1318 agreement that produced a new royal council. Scottish forces, meanwhile, extended into northern England, threatening York. Edward sent an army north but found it difficult to feed and pay the soldiers. Edward's one success at this time was defeating Edward Bruce, Robert's brother, who had taken control of Ireland and declared himself king there. Meanwhile, in Scotland, Robert the Bruce had rallied the other nobles around his banner, and they all gathered at the monastery of Arbroath on April 6, 1320 to issue the Declaration of Arbroath, setting themselves free from all other masters. The threatened civil war finally began in 1321. A few years before that, Edward had taken a new favorite, Hugh Despenser the Younger. His father had served both king Edwards, and Hugh the Younger had alienated many of the barons by building up a power base in Wales at their expense. Just as he had with Gaveston, Edward lavished titles and other gifts on Hugh the Younger. The barons had finally had enough.

Edward still had control of a large army, however, and the baronial rebellion was short-lived. Royal forces defeated the rebel forces at the Battle of Boroughbridge on March 16, 1322. Edward was particularly savage in his retribution, ordering the execution of a number of nobles, including Lancaster. He also stripped many of the rebelling barons of their lands and gave it to the Despensers. Also in 1322, Edward set out again for Scotland, again at the head of a large army. This one, too, ran out of food and money because Robert the Bruce refused to engage the English army in battle. The two leaders finally agreed to a 13-year truce. Edward returned home to a very unstable situation. Hugh Despenser the Younger alienated even more of what should have been the king's supporters, and discontent grew among the common populace. As well, one of the rebelling barons that Edward didn't have killed, Roger Mortimer, escaped and went to France. Twin challenges awaited Edward in France in the early 1320s. The first was that he had fallen out with the new French king, his brother-in-law Charles, over the administration of Gascony, which had been in Edward's family possessions for many years. Preventing a military conflict was the intercession of Edward's wife, Isabella, who was Charles's sister. The resulting 1325 treaty generally favored France, but it avoided war. Also at this time, Isabella had fallen out with Edward, for a variety of reasons, and had taken up with Mortimer, who had a long list of grievances with the king. They had powerful friends and money to pay for an invasion army, and they sailed across the English Channel in September 1326, intent on attacking Edward. Accompanying them was King Edward's son Edward, who was 13.

King Edward attempted to hunker down in London, but the city turned against him. He and the Despensers fled the city on October 2. A mob set about ravaging the city and killing Edward's supporters and members of his household. Meanwhile, Mortimer and Isabella and their army pursued the king. They found him in Wales, and an armed guard took him first to Monmouth Castle and then to Kenilworth, a fortress belonging to Lancaster. Out of options, Edward agreed to abdicate. He did so on January 21, 1327. His son was crowned King Edward III on February 2. Mortimer and Isabella were declared regents. The Despensers had been separately executed. Edward, once again Edward Caernarfon, was held in several locations, primarily Berkeley Castle in Gloucestershire. Rumors of plots to free him abounded, but none took shape. He died on September 21. Historians do not agree on the cause of his death. His body was eventually taken to Gloucester Abbey. The legacy of Edward II is a complicated one. He was compared, fairly or not, to his father, who enjoyed great success as a monarch and as a solider. He was a patron of the Church and a friend to education, starting three universities, including King's Hall in Cambridge. As well, the role of Parliament grew under his reign. He is remembered first and foremost, however, for his political and military failings and for his abdication. First page > His Father's Shadow > Page 1, 2 |

|

Social Studies for Kids

copyright 2002–2025

David White