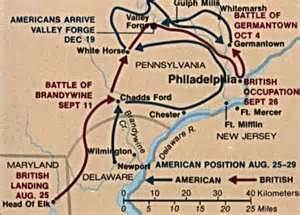

The Continental Army suffered through a crushing winter at Valley Forge but emerged more resilient, if lacking in numbers. Philadelphia was then the capital of the U.S. It was before Saratoga, in August, that a large contingent of British troops sailed from their stronghold in New York to Pennsylvania, with the aim of capturing the capital. Seeking to prevent this, General George Washington and his troops attacked the British at Brandywine, on September 11, 1777. The resulting rout sent the Americans reeling and left Philadelphia open to occupation. Stunned members of the Continental Congress fled the city and re-established the capital in York, Pa. On September 26, the British occupation of Philadelphia commenced.

Like Whitemarsh, Valley Forge was a good place for defense. High on a plateau, the army encampment was protected by a river and two shallow creeks. The village itself was named for the iron-making facilities owned by two Quaker families. Washington and his shivering, beleaguered men arrived at the camp and discovered that the British Army had followed up their victory at Brandywine with a quick sortie to Valley Forge to plunder its military and other supplies. Also, promised food and clothing from the Continental Congress had yet to arrive. About 12,000 men crowded the camp, suffering from lack of food, clothing, shoes, and shelter. One of Washington's first orders was to build log huts. In each smallish hut, 12 men were to sleep in a six-foot-tall hut the sides of which measured 16 feet by 14 feet. Featuring a fireplace and having nothing but a cloth for a door, the floorless huts were damp, drafty, and smoky. Temperatures were near freezing for several weeks, and many men who lacked proper clothing or shoes succumbed to the conditions, either partially, through amputation, or totally. Illness was a prime enemy. Soldiers suffered from typhus, dysentery, typhoid, and pneumonia. In all, about 2,000 died. Fearing an outbreak of smallpox, Washington ordered thousands inoculated. The country's first military hospital, run by an elderly German physician and his two sons, was built at Yellow Springs, 10 west of the Valley Forge encampment. A three-story building housed up to 300 men. Washington visited on occasion.

Food was short. A soldier's consisted mainly of firecake, a fried combination of flour and water. The roads all around Valley Forge were frozen and rutted, making it difficult for supplies of any kind to get to the army. Inconsistent supply lines were made worse by the weather. Congressional money was next to worthless, and many farmers hid their stock rather than agree to sell it to the Continental Congress. One bright spot came in the arrival of Baron von Steuben, a Prussian Army veteran who, on the recommendation of Benjamin Franklin, got the job as drill instructor for the Continental Army. Von Steuben spoke little English. He spoke German and French and relied on two of Washington's aides, Alexander Hamilton among them, to translate. The baron built up the troops' marching and fighting skills, along with their morale. He trained groups of 100, then urged them to train their fellow soldiers. He even produced a French-language drill book, "Regulation for the Order of Discipline of the Troops of the United States", which was translated into English. He turned raw troops (who, one source relates, used their bayonets to hold food over the fire) into more confident soldiers. This training coincided with an increase of food and other supplies, thanks in large part to the influence of the newly appointed quartermaster Nathanael Greene. As spring thaws brought warmer temperatures, so the cleared roads brought food and supplies. Staff from a baking company arrived in March and supplied the troops with fresh bread. An extra month's pay arrived unexpectedly, in March. Supplies in the nearby Schuylkill River were plentiful in April, and starved men had their fill. Also in April came the news that France, encouraged by the American victory in Saratoga, had agreed to fight against the British Army. French supplies began to arrive at Valley Forge. In response, Howe gave the order to leave Philadelphia. Hearing this, Washington gave the order to leave Valley Forge. British troops completed their evacuation on June 18, 1778. The result of >Baron von Steuben's training could be seen the very next day, at the Battle of Monmouth, in New Jersey. Although neither side could claim a victory, the British Army did retreat from the field of battle, in stark contrast to the routs a year earlier at Brandywine and Germantown. A number of men who would go on to more famous things spent the winter at Valley Forge:

|

|

Social Studies for Kids

copyright 2002–2025

David White

Washington tried again, on October 4, at Germantown, just north of Philadelphia. The result was the same as at Brandywine. Washington moved his troops to Whitemarsh, about 20 miles away from Philadelphia, and set up a defensive encampment. British troops under Gen. William Howe were by then ensconced in Philadelphia and had no desire to come out and fight. With winter coming on, Washington led his army to winter quarters at nearby Valley Forge. The troops left on December 12 and reached Valley Forge, 13 miles away, on December 19, their arrival delayed by snowstorms, sleet, and icy roads.

Washington tried again, on October 4, at Germantown, just north of Philadelphia. The result was the same as at Brandywine. Washington moved his troops to Whitemarsh, about 20 miles away from Philadelphia, and set up a defensive encampment. British troops under Gen. William Howe were by then ensconced in Philadelphia and had no desire to come out and fight. With winter coming on, Washington led his army to winter quarters at nearby Valley Forge. The troops left on December 12 and reached Valley Forge, 13 miles away, on December 19, their arrival delayed by snowstorms, sleet, and icy roads.