The Road to the Civil War

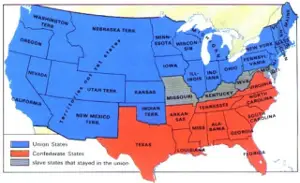

The Republican Party, formed in 1854 in the wake of the dissolution of the Free Soil Party, the Know-Nothing Party, and the Whig Party, had the abolition of slavery as one of its cornerstone policies. That party's second presidential candidate, Abraham Lincoln, won the presidency in 1860, despite not even being an option for voters in most southern states. His victory was short-lived, however, as South Carolina seceded from the Union on December 20, 1860. Mississippi, Florida, Alabama, Georgia, Louisiana, and Texas followed in the next few weeks. These seven states formed their own Confederacy and chose their own capital, Montgomery, Ala. They eventually named their own legislature and executive, Jefferson Davis. Secession

But the colonies-turned-states still possessed a strong sense of state identity. This idea was very much in line with the thinking of the leaders of the Democratic-Republican Party, such as Thomas Jefferson and James Madison. Jefferson, in the Kentucky Resolutions, and Madison, in the Virginia Resolutions, put forward the idea that states could, if they thought that directions from the federal government were an abuse of power, choose not to follow those directions. These Resolutions were written in the 1790s, in response to the Alien and Sedition Acts, which many in the Democratic-Republican Party thought were an over-reach of federal power. The argument at the root of the Nullification Crisis was ostensibly over a tariff, a tax on goods transferred from one entity to another. Transactions could take place between companies, between states, or between countries. The Tariff of 1828 was deeply unpopular in parts of New England and the South and was so detrimental to South Carolina, in particular, that that state began to agitate for a political response. South Carolina's own John C. Calhoun was Vice-president at the time, having been elected with Andrew Jackson in 1828.  p>The common epithet given to this unpopular tax was the "Tariff of Abominations." Because of a post-War of 1812 economic downturn, several states, including South Carolina, were suffering. The new nation had suffered its first financial crisis, called the Panic of 1819; and South Carolina had not really recovered. Virginia in 1826 passed a resolution in the state legislature, asserting that the tariff was unconstitutional and using the Virginia and Kentucky Resolutions as justification. Even though the 1828 tariff was an "abomination" in equal parts Northeast and South, depending on which state the poll would have been taking, it was the Southern states that were generally more seriously affected and one Southern state, South Carolina, that did something legislative about it. Southerners had lined up in opposition to the Tariff of 1828 and had thought that the newly elected Jackson, from the South, would get to work dismantling the tariff. He did no such thing, even at great urging from Calhoun, his Vice-president. As the state economy continued to struggle, the mood in South Carolina continued to sour and many began to call for nullification. Calhoun felt so strongly about the issue that the resigned as Vice-president (one of only two ever to do so) in order to serve in the Senate, where he thought he could more effectively take up the nullification cause. In the meantime, Jackson and Congress had come up with a weakened tariff, the Tariff of 1832. Most Northerners and half of Southerners in Congress voiced their approval. Calhoun and the South Carolina delegation did not. Their state legislature declared both the 1828 and 1832 tariffs unconstitutional and unenforceable within the state borders of South Carolina beginning on February 1, 1833. p>The common epithet given to this unpopular tax was the "Tariff of Abominations." Because of a post-War of 1812 economic downturn, several states, including South Carolina, were suffering. The new nation had suffered its first financial crisis, called the Panic of 1819; and South Carolina had not really recovered. Virginia in 1826 passed a resolution in the state legislature, asserting that the tariff was unconstitutional and using the Virginia and Kentucky Resolutions as justification. Even though the 1828 tariff was an "abomination" in equal parts Northeast and South, depending on which state the poll would have been taking, it was the Southern states that were generally more seriously affected and one Southern state, South Carolina, that did something legislative about it. Southerners had lined up in opposition to the Tariff of 1828 and had thought that the newly elected Jackson, from the South, would get to work dismantling the tariff. He did no such thing, even at great urging from Calhoun, his Vice-president. As the state economy continued to struggle, the mood in South Carolina continued to sour and many began to call for nullification. Calhoun felt so strongly about the issue that the resigned as Vice-president (one of only two ever to do so) in order to serve in the Senate, where he thought he could more effectively take up the nullification cause. In the meantime, Jackson and Congress had come up with a weakened tariff, the Tariff of 1832. Most Northerners and half of Southerners in Congress voiced their approval. Calhoun and the South Carolina delegation did not. Their state legislature declared both the 1828 and 1832 tariffs unconstitutional and unenforceable within the state borders of South Carolina beginning on February 1, 1833.

President Jackson responded on two fronts, advocating the use of military force to bring South Carolina into line while also convincing Congress to work on yet another tariff, one that South Carolina might finally approve. Congress passed both a Force Bill and the Compromise Tariff of 1833. South Carolina responded by repealing its nullification ordinance.

In a sense, both Jackson and South Carolina could claim victory. The new tariff was weak enough to gain the support of the recalcitrant South Carolina and the rest of the South, so state agitation was effectively at an end. South Carolina got what it wanted, and so did the Federal Government. Both sides avoided a military showdown (although Jackson might have helped convince South Carolina of the futility of this by sending a couple of Navy ships to Charleston). The idea of a state's being able to step outside the jurisdiction of the Federal Government didn't go away, however. South Carolina and the other Southern states revived it after Lincoln's election and carried out the theory to its greatest logical conclusion, seceding from the Union and forming the Confederate States of America. Lincoln took office on March 4, 1861. Thirty-nine days later, the Civil War began, with an attack on Fort Sumter. First page > Early Commonalities > Page 1, 2, 3, 4, 5 |

|

Social Studies for Kids

copyright 2002–2026

David White

One major development in the history of American slavery was the famous Supreme Court case Dred Scott v. Sandford. In

One major development in the history of American slavery was the famous Supreme Court case Dred Scott v. Sandford. In