Prohibition in America

Prohibition in America was born from a desire to improve public health, had a high-water mark of a couple of decades in which it was the law of the land, and then receded, to be a national footnote if still a state priority. The temperance movement grew out of a religious revival in the early 19th Century and also out of a growing number of women speaking out against alcohol as a cause of domestic abuse. The temperance movement was up against a powerful tradition, however. Some sources say that in the 1830s, alcohol consumption was three times the national average as Americans consumed in the 2000s. One of the first true tests of the new Constitutional government was the Whiskey Rebellion, a protest against a new government tax on whiskey.

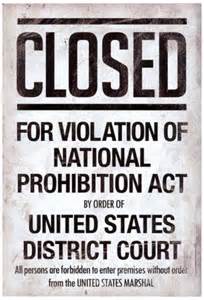

Maine passed a statewide prohibition law in the mid-19th Century but repealed it a few years later. Such laws were being discussed in other states as well. In 1873, one of the larger organizations, the Women's Christian Temperance Union (WCTU), issued a call for a ban on the sale of alcohol, a plea echoed by the Anti-Saloon League (ASL) several years later. Members of these organizations and people sympathetic to their cause, men and women, demonstrated publicly against the sale of alcohol. Demonstrations took place where alcohol was sold, at saloons and bars, and at public rallies. The Kansas State Constitution outlawed alcohol in 1881. The temperance movement was largely nonviolent, although one particularly famous leader, Carrie Nation, made a name for herself by using a hatchet to break saloon mirrors and windows and to split open kegs of beer or whiskey. Arrested several times, she became famous for her temperance tactics. The sustained efforts of Nation and other leaders of the temperance movement were rewarded with the passage by Congress and subsequent ratification of three-quarters of the states of the 18th Amendment. The passage of the Volstead Act (over a veto by President Woodrow Wilson), on Oct. 28, 1919, placed some particulars around the idea of prohibition. And beginning in 1920, prohibition was law.

The 18th Amendment and the Volstead Act also contained certain loopholes that savvy entrepreneurs exploited. For example, it wasn't illegal to make or consume wine or cider in the home, provided people didn't make more than 200 gallons of each a year; in the year between the passage of the Amendment and the day it went into effect, many people stockpiled liquors and wines in home cellars. This naturally favored people who had access to a lot of money when they needed it, not necessarily people who had little left over after they used their regular paycheck to meet their basic needs. Also not prohibited by Prohibition was the use of alcohol for medicinal purposes. Many people got around the new laws by getting their doctors to prescribe medicinal prescriptions of alcohol. Many people simply ignored the laws. The number of "speakeasies," where alcohol could be bought for a price, skyrocketed. Sensing an opportunity (or exploiting an existing one), gangsters moved into (or expanded into) new territory. Large cities such as Chicago and New York became known for having thousands of illegal outfits. One of the most famous of the gangster-owners was Al Capone (whose annual income was said to exceed $60 million). By no means the only such character in the Chicago area or in the business, Capone was nonetheless the most recognizable and the most feared. Gangsters and other unsavory characters became suspects as well in crimes far more devastating than violating the requirements of the Volstead Act. The illegal transport of alcohol, or "bootlegging," was rampant as well, with many law enforcement officers accepting bribes for not reporting the bootlegging or not arresting the perpetrators. This extended to other countries, which did not have prohibition laws. The smuggling into America of alcohol from Canada, Mexico, and Caribbean countries was a major concern for the Coast Guard, the FBI, and for other law enforcement agencies. The large, open nature of America's land borders and ports made for a plethora of opportunities for bootleggers to evade capture.

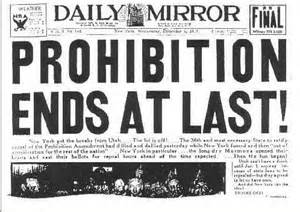

The desire for continued support for Prohibition waned. It was not universally approved, by any means, and onetime proponents joined forces with opponents to bring about the end. One main economic factor in this was the loss of a considerable amount of revenue that, until Prohibition, had been paid into Government coffers in the form of tax on alcohol. In the presidential election of 1932, the Democratic candidate, New York Gov. Franklin D. Roosevelt, promised to repeal Prohibition if he were elected. He won, and he did, guiding Congress in the approval of the 21st Amendment, which was quickly ratified by the requisite number of states. |

|

Social Studies for Kids

copyright 2002–2025

David White

It wasn't just women in the temperance movement, though, as men campaigned to ban alcohol as well. Statewide prohibition efforts became popular, beginning in the early part of the 19th Century. One of the first national temperance organizations was the American Temperance Society (ATS), formed in 1826. Within a decade, the ATS had 1.5 million members.

It wasn't just women in the temperance movement, though, as men campaigned to ban alcohol as well. Statewide prohibition efforts became popular, beginning in the early part of the 19th Century. One of the first national temperance organizations was the American Temperance Society (ATS), formed in 1826. Within a decade, the ATS had 1.5 million members.  The Federal Government soon ran into trouble enforcing the law, however. It was suddenly illegal to produce, transport, or sell alcoholic beverages; but such producers, transporters, or sellers had to be caught in the act and then brought to justice. The sheer size of the alcohol industry in America at the time made for considerable challenges for local, state, and federal law enforcement officials.

The Federal Government soon ran into trouble enforcing the law, however. It was suddenly illegal to produce, transport, or sell alcoholic beverages; but such producers, transporters, or sellers had to be caught in the act and then brought to justice. The sheer size of the alcohol industry in America at the time made for considerable challenges for local, state, and federal law enforcement officials. Thus, the 18th Amendment and the Volstead Act, enacted to prevent unsavory and/or socially damaging activities, had resulted in perhaps more of the kind of thing that Prohibition, the "noble experiment," as it was known to some, had been designed to prevent.

Thus, the 18th Amendment and the Volstead Act, enacted to prevent unsavory and/or socially damaging activities, had resulted in perhaps more of the kind of thing that Prohibition, the "noble experiment," as it was known to some, had been designed to prevent.