|

|

The Dred Scott Case

Part 3: Stunning Decision

Time marched on again. The country became even more divided. The Court heard the case in early 1856. The arguments were remarkably similar to the ones advanced in the Circuit Court case. The Court, however, delayed its decision in order not to coincide with the presidential election. In fact, the Court ordered the case to be reargued. This occurred, and the justices met to discuss the case on February 14, 1857.

Initial discussions reveal that most justices favored denying Scott's arguments but not considering the larger issue of whether he was a citizen or had the right to sue. (This is usually the pattern that the Court follows, preferring to issue narrow rulings that apply only to the facts of a case and not issue broad, sweeping opinions that rewrite laws.) In fact, the Court initially assigned Justice Nelson to write the opinion. This was not the final word, however, because when Nelson came back to the other justices to present his opinion, he discovered that they no longer wanted him to represent them, preferring instead to have the majority opinion written by the Chief Justice, Roger Taney.

Taney, a former U.S. Attorney General from Maryland, believed that slavery was moral and legal. Under his leadership, the Court had ruled in two previous cases (Prigg v. the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania and Moore v. Illinois) that slavery was protected and that, further, slaveowners could not be denied their "property." Taney, a former U.S. Attorney General from Maryland, believed that slavery was moral and legal. Under his leadership, the Court had ruled in two previous cases (Prigg v. the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania and Moore v. Illinois) that slavery was protected and that, further, slaveowners could not be denied their "property."

Building on this, Taney wrote in his opinion in Dred Scott v. Sanford that Scott, as a slave, had no rights as a citizen of the United States. And since he was not a U.S. citizen, he could not sue his owner. Sanford, as a slaveowner, had a right to keep his property under the Fifth Amendment, which prohibits the "denial of property without due process of law."

On the related matter of whether Scott was a free man because he had lived in Illinois and Wisconsin Territories, Taney relied on the distinction that because Scott was technically a slave when he filed the lawsuit (because he was living in Missouri, a slave state), he was still a slave under the law, no matter where he lived or when.

It was a dual blow to Scott's chances to gain his freedom and for abolitionists' efforts to expose slavery as the evil it was.

This should have been the end of it, many historians conclude. If Scott wasn't a citizen, then he couldn't sue; it should have been case closed.

But this is not what happened. Taney went further, ruling that the Missouri Compromise itself was unconstitutional. His argument was that because that Act of Congress deprived slaveowners of their property, the Act itself was counter to the Constitutional right described under the Fifth Amendment.

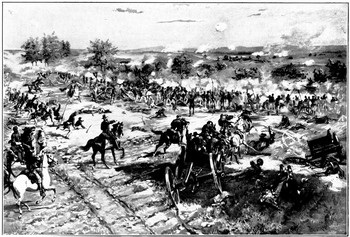

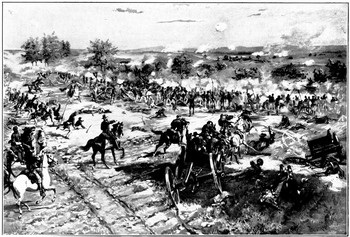

It was a stunning opinion, one whose author hoped would end the slavery question once and for all, putting the institution under the protection of the Constitution forever. Instead, it inspired the antislavery North to dig in its heels even deeper in its cause for the abolition of slavery. Political leaders in the North got a lot of mileage out of the idea that the Dred Scott decision, if interpreted a certain way, could be used to argue that slavery could be legal in New York, a state that had outlawed slavery. Those leaders' counterparts in the South used the decision to justify their adherence to a cruel, inhumane practice that would find its death knell only at the barrels of thousands of Union rifles and cannon.

Dred Scott became a symbol of all that was wrong with slavery, and the decision that bore his name became a lightning rod for the conflict that would eventually divide—and then unite—the nation.

First page > Prelude to "Justice" > Page 1, 2, 3

|

|

Taney, a former U.S. Attorney General from Maryland, believed that slavery was moral and legal. Under his leadership, the Court had ruled in two previous cases (Prigg v. the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania and Moore v. Illinois) that slavery was protected and that, further, slaveowners could not be denied their "property."

Taney, a former U.S. Attorney General from Maryland, believed that slavery was moral and legal. Under his leadership, the Court had ruled in two previous cases (Prigg v. the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania and Moore v. Illinois) that slavery was protected and that, further, slaveowners could not be denied their "property."