The Cuban Missile Crisis: World War III Narrowly Averted

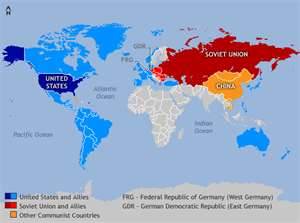

Part 1: Cold War Backdrop The Cuban Missile Crisis took the world to the brink of nuclear war in an intense diplomatic struggle during a couple of weeks in October 1962. The Crisis had its origins in the Cold War, the struggle between Western and Eastern powers that dominated the second half of the 20th Century. After the end of World War II, many of the world's most populous nations divided themselves up into two camps: Communist and not Communist.

The Soviet Union was the prime mover in the Communist sphere, also having a controlling interest in most nations in Eastern Europe. In response to the formation of NATO, the U.S.S.R. and its Eastern European allies formed a similar mutual support strategy called the Warsaw Pact. The Cold War played out largely far from the U.S. (including crises in Berlin and the Korean Peninsula) until Fidel Castro became the leader of Cuba, an island nation 90 miles off the coast of Florida. As the result of a revolution in 1959, Castro was in charge in Cuba. He made no secret of his distaste for the U.S. and its leaders, and the two countries became locked into a trade dispute. Among the particulars of this trade dispute were a refusal of American markets to buy Cuban sugar and a refusal of American suppliers to sell oil to Cuba. Castro's purchase of military equipment and weapons from Eastern European nations didn't endear him to Western leaders, either. American leaders, including newly elected President John F. Kennedy, made no secret of their dislike of Castro, especially his preference for Communism. Castro became an ally of the Soviet Union, and the Cold War came closer to the U.S. mainland. In early 1961, the American Central Intelligence Agency trained a group of Cuban exiles with the express purpose of invading Cuba and overthrowing Castro. In 1961, the Cuban military easily repelled the invasion, which came to be known as the Bay of Pigs invasion because of its location. The U.S. government could claim that it did not participate directly in the invasion attempt, but the Cuban exiles weren't given much training or support in the end, and so the island remained firmly in Castro's hands. Understandably, Cuba and the Soviet Union cried foul. Later that year, Soviet leader Nikita Khrushchev hinted at a takeover of West Berlin, which was the only part of the former German capital city not occupied by Communist forces. More broadly, Khrushchev made it known that he intended for Soviet forces to permanently occupy East Berlin. At a meeting in Vienna, Kennedy ostensibly agreed to the permanent occupation but made it clear that Western nations would continue to assert their right to occupy West Berlin. The result was the Berlin Wall. On August 13, 1961, fortifications divided the city, creating two cities and a long-term division between East and West.

The combination of the U.S.'s poorly supported invasion at the Bay of Pigs and Kennedy's refusal to insist on a full-throated defense of Berlin emboldened Khrushchev to support Castro more militarily. Thinking that Kennedy wouldn't object, Khrushchev convinced Castro to allow Soviet missiles onto Cuban soil. In September, Soviet ships carrying nuclear missiles began arriving in Cuba. The Soviet Union at the time had very few intercontinental ballistic missiles (ICBMs) but had a large number of medium- or intermediate-range ballistic missiles (IRBMs). Placing IRBMs in Cuba would enable the Soviet Union to target the entirety of the U.S. with nuclear warheads. (This was already the case in reverse, since the U.S. had already deployed nuclear missiles in Turkey that could strike just about anywhere in the U.S.S.R.) American U-2 spy planes had flown secret missions over Cuba and had taken pictures that confirmed the existence of surface-to-air missiles at eight locations in Cuba. Soviet officials, when confronted with intelligence to this effect, insisted that the missiles were for defensive purposes only. Further investigation of the photos convinced American intelligence and military experts that the missiles were, in fact, nuclear in nature. Next page > Nearly a War > Page 1, 2 |

|

Social Studies for Kids

copyright 2002–2026

David White

The United States was the prime mover in the non-Communist sphere. To counter the spread of Communism, the U.S. joined with countries of Western Europe to form the North Atlantic Treaty Organization. Members of NATO agreed to support one another if attacked.

The United States was the prime mover in the non-Communist sphere. To counter the spread of Communism, the U.S. joined with countries of Western Europe to form the North Atlantic Treaty Organization. Members of NATO agreed to support one another if attacked.