The Comstock Lode

Miners continued to find gold and silver during this time and off and on, for a number of years. One estimate of the total worth of the amount found, dug up, and dispatched with from the Comstock's initial take through the end of 1881 was more than $300 million. Stocks in Comstock mines rose and fell, soared and plummeted. One example, that of the Belcher mine, is representative: One share of stock in that mine in 1868 was worth $430; the same share in 1872 was worth $1,525; the same share in 1878 was worth $2. The scale of fortune and then misfortune spelled the success and/or ruin of many. The fortunes of Comstock himself are a cautionary tale as well. He ran out of money in 1862 and, unable to get credit or loans, left. He died poor in 1870, in Montana, of a self-inflicted wound.

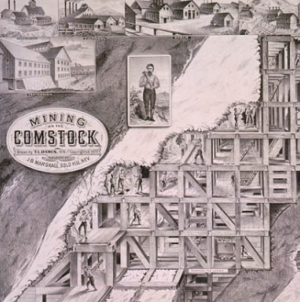

The first hauls of silver and gold were dug out of water or from surface deposits. Miners quickly had to go underground to continue the supply. The tunnels that miners dug were subject to cave-ins because of the softness of the ore, and so one of several technological advancements associated with this time and place in history was Square Set Timbering, a creation of German-born engineer Philipp Deidesheimer. As early as 1860, he had perfected a modular cube-shaped collection of wood, each piece up to 7 feet tall and up to 6 feet wide. Put together, they resembled an upside-down letter U; a diagonal brace helped with support. Another utility of the cube-shaped wood structures was that they had "trapped" space in between the wood braces; workers could put in that space rocks and dirt that they would have otherwise have to carry up to the surface. The cubes could be stacked, providing support in tunnels far underground. The deepest excavations stretched more than 3,000 feet beneath the surface. The depth proved catastrophic to existing wooden supports, but the Square Sets solved that problem and soon became a standard equipment method far and wide. Another problem that required new solutions was the relatively arid nature of the area in which the Comstock Lode ore veins were discovered. Water was not plentiful in the area and so had to be brought in as the area population increased. People and companies arranged for water containers to be brought in; some companies also built pipes so that water could flow in from reservoirs near and far.

A related problem was that of water underground. Having never dug in these areas before, miners didn't exactly know when and where they might encounter underground water. Many times, sudden flooding would halt mining production in its tracks while miners removed the unwanted water. More dangerously, some of this area was populated by hot springs, and the resulting torrent of suddenly released water could harm the unwary minder. One main solution to this problem of underground water the Sutro Tunnel, a four-mile-long passageway 9.5 feet high and 7.5 feet wide that was built underneath existing tunnels and acted as a drain. Named after engineer Adolph Sutro, the tunnel connected Comstock territory with the valley near what is now Dayton, allowing more than 4 million gallons a day to be transported away from the mines. The tunnel was wide enough for horse-drawn carts to pass through.

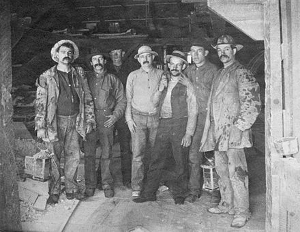

To a large extent, digging the mines and mining the gold and silver were immigrants–from Canada, German, Great Britain, Ireland, and Italy. These itinerants were expected to work hard for little money and be happy with their lot in life. They were the subject of intense discrimination from those who were born in the United States. Exceptions were the wealthy immigrants, like Sutro, whose fortunes made him relatively immune from such persecutions. Also in the anti-immigrant vein, Americans in the area of the Comstock Lode held particular vehemence for Chinese immigrants, even though they had played a large part in the construction of the nationwide railroad. By 1880, the gold and silver had begun to run out. Only the Delamar mine continued to churn out ore regularly. Operations shut down, and miners and businessmen left in droves. The county population in which the Comstock Lode surface land resided dropped from 25,000 at its height to 3,500 by 1900. Silver, however, was the prime mover behind the rise of the State of Nevada, which took as its moniker the "Silver State." Congress had incorporated the First page > Early Days > Page 1, 2 |

|

Social Studies for Kids

copyright 2002–2026

David White

Nevada Territory in 1861. Even more settlers came after the passage of the 1862

Nevada Territory in 1861. Even more settlers came after the passage of the 1862