The American Civil War

Part 9: The Road to Petersburg For five weeks in November and December 1864, the troops under Union Gen. William T. Sherman personified their commander's maxim that "war is hell" by devastating the Georgia countryside, in an effort to sap the morale of the Confederate troops and populace.

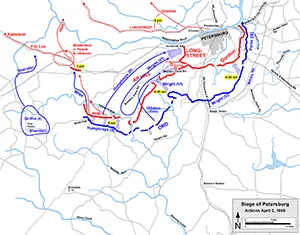

Sherman (left) had struck a symbolic blow on September 2 by capturing Atlanta, defeating a pair of well-known Confederate commanders, Joseph Johnston and John Bell Hood, in the process. Neither Johnston's defensive tactics nor Hood's aggression seemed to faze Sherman and his Army of the Tennessee, as they steadily wore down and defeated the armies in their path. Adding the Army of Georgia to the mix, Sherman and company set off from Atlanta on Nov. 15, 1864, with 62,000 men. They ignored a western feint by Hood, designed to draw them back into Tennessee, and headed for the Atlantic Ocean. Meanwhile, Maj. Gen. George Thomas and the Armies of the Cumberland and the Ohio were running interference, preventing whatever was left of Hood's army from striking at the rear of Sherman's overland invasion force. The central government of the Confederacy found it increasingly difficult to finance the war effort, with either men or money. The various states had control of their militias and lent them to the central war effort with varying degrees of regularity. Confederate soldiers originally signed on for a 12-month term. A great many of those were killed in action or on the march or in a military hospital or in any number of accidents. However, a great many also served out their one-year terms and had no desire whatever to return to the fighting. The Confederate congress had been forced to enact the first conscription law in the history of the American continent. Enacted on April 16, 1862, this law required men ages 18–35 to serve for three years. Not enough men in that age range were available, and so the congress, just seven months later, raised the upper age limit to 45. A final change to the age of conscription came on Feb. 17, 1864, when the age range became 17–50. The North had enacted conscription laws as well, as early as 1863, along similar lines. Enthusiasm was not always high. One particularly large draft riot occurred in New York City just days after the Northern victory at Gettysburg. Finances were a problem for the Confederacy as well. For a start, Article I, Section 9.9 of the constitution stipulated an exact plan for the what and the why: "All bills appropriating money shall specify in Federal currency the exact amount of each appropriation and the purposes for which it is made." Early on, the Confederate congress instituted a tax on all property that included slaves. The states found this money through borrowing rather than by collecting it from their citizens. This gave property owners more money to spend on their possessions and upkeep but created large amounts of debt that the states struggled to repay and the central government was forbidden from relieving. In 1863, the Confederate congress widened the net, introducing a direct income tax and a tax on agricultural products, including livestock. By this time, the farmers who bore the burden of such a tax were struggling and found it expedient–and, in many cases, rather easy–to avoid paying. A central government that depended on its member states to supply men, money, and materiel might struggle to be in control of its own destiny. This was certainly the case with the Confederacy as the years went by: roads, bridges, and (perhaps most strategically) railroads languished in disarray, the funds for their repair tied up in red tape in Richmond. On a more general level, many things large and small went without repair, as people prioritized other things or did without. Meanwhile, the North had the machinery of industry and a seemingly endless of men, supplies, and weapons. After Lee and his men retreated from Gettysburg, the North was free of military conflict and so had none of the upkeep associated with a countryside dotted with soldiers and battlefields. The Northern population was higher and, therefore, so was the tax base. People in the North grumbled about paying taxes, as they always did, but the Emancipation Proclamation had framed the prosecution of the war as a war against the immoral practice of slavery and that was enough to convince people to continue to pay taxes, to continue to send their soldiers off to war, to continue to fight for what many viewed as a higher cause. The Confederate government, hamstrung by a lack of central authority, proved unable to provide for a war that was increasingly going the way of the Union. Staring down the barrel of defeat, many in the Confederate congress entertained the idea of a negotiated peace. Indeed, Lincoln and Seward took part in a peace conference with Stephens and other Confederacy representatives at Hampton Roads, Va., on Feb. 3, 1865. The two sides couldn't agree, and the Confederacy limped on. In March 1865, the number of Union troops in the area of Petersburg and Richmond was about 125,000. More were on the way. In the Shenandoah Valley but, having finished operations and returning, was the cavalry commander Sheridan, along with 50,000 more troops. Also soon to converge on the area was Sherman at the head of another large force, the one that had taken Atlanta and gone on the "March to the Sea" and had laid waste to the Carolinas. By contrast, Lee had a force of 50,000 that still had fighting spirit but was weakened by disease and a lack of food and other supplies; as well, the desertions from the Confederate army had begun to rise. Lee devised an attack to be led by Maj Gen. John Gordon that was to break through the Union lines. The location for this was Fort Stedman, and the attack, on March 25, succeeded for a time, punching a 1,000-foot-long hole in the Union line. However, the Union army, which had been planning an attack of its own, soon recovered and punched back with devastating force, opening up on the Petersburg defenses with every piece of heavy artillery it had. Gordon and his men, their numbers dwindled significantly, retreated.

Sheridan and his cavalry had returned by the end of March, arriving from the west. Lee sent nearly 10,000 men under Maj. Gen. George Pickett to Five Forks, to protect that town and its accompanying Southside Railroad. Sheridan and his men easily won the Battle of Five Forks, on April 1. Pickett wasn't even there on the day of the battle and was relieved of his command. The following day, Grant ordered a mass assault on the Confederate line. Union troops made the kind of progress that they had hoped to make many months earlier, forcing the defenders back to the inner ring of fortifications. While riding between the lines to encourage the defenders, Confederate Gen. A.P. Hill, one of Lee's most trusted and longest-serving commanders, fell to Union bullets. Darkness stilled the guns for the day. On that same day, however, Lee had informed Confederate President Jefferson Davis and the rest of the government that he was leaving Petersburg. Evacuations were taking place even as other defending troops were fighting to protect them. The Union occupied Petersburg at dawn on April 3 and Richmond at the end of that same day. Next page > And in the End > Page 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10 |

|

Social Studies for Kids

copyright 2002–2026

David White