The Missions of California

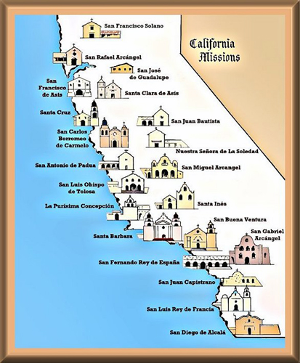

The Spanish built and maintained nearly two dozen missions up and down the California coast in the late 18th Century and early 19th Century. Essentially designed to support a large effort to convert Native Americans to Christianity, the missions were famous for the missionaries who lived there and the buildings they constructed.

In 1769, Father Junipero Serra founded the first California mission, the Mission San Diego de Alcalá, in what is now San Diego. In all, the Spanish built 21 missions, as far north as Sonoma, covering 650 miles. They were built about 30 miles apart and were designed to allow a person riding a horse to get from one mission to another within a day. (The same journey on foot would take a person as long as three days.) Serra became something of a mission progenitor, establishing eight more before he died, in 1784. The other missions were these, going north from San Diego:

The idea of the mission was to spread the practice of Christianity, and priests and soldiers did this with varying degrees of severity. In some cases, conversion was dictated at the point of a sword. Within the mission community, religious instructors would invite local people to attend religious training; those attending such training sessions lived within the mission and were expected to do manual labor and learn the Spanish language. Some Native Americans entered into the mission system voluntarily; others had no choice in the matter. The missionaries' desire to "civilize" the native population fueled what in many cases was a system of forced labor. The training of such "neophytes," as they were known, began with a Christian baptism, which followed an initial period of instruction in Christian texts, primarily the Bible, and customs. Estimates are that across the entire mission system, Spanish missionaries baptized more than 53,000 Native Americans.

A typical day at a Spanish mission began with Mass at sunrise, followed by morning prayers and religious instruction. After a substantial breakfast, the trainees got to work. Men did tasks that required manual strength, such as plowing and threshing, shearing of sheep, tanning of hides, and construction of buildings. Stronger women were assigned tasks like grinding flour or carrying materials to men doing the building. Other women tended to knitting, weaving, cooking, and other tasks considered more domestic. A typical workday was six hours, punctuated by a midday meal and a two-hour rest period and then followed by an evening rosary and meal. Progressively, the mission officials designated the equivalent of three months out of the year holidays, either civil or religious; on these days, work was not required. Religious observances were rarely missed on these days. The Spanish government had envisioned the California missions to be self-sufficient, so missionaries, soldiers, and especially the Native Americans living within the missions' walls produced as much of the things that they needed as possible. They grew their own food, made their own clothing and soap and paint and household items like rugs and linens and furniture and cookware. Animal husbandry and ranching were common, of cattle and sheep and goats and pigs, all of which had been brought north from Mexico. Some animals were grown as sources of food, and others were used to make leather and wool. Also common was cultivation of various flour-generating grains like barley, corn, and wheat. Missionaries had brought with them seeds of many fruits, among them apple, grape, orange, peach, and pear. Some locations and populations had a better time of it than others in their pursuit of self-sufficiency. Some missions proved very profitable, churning out grain, cattle, and other goods that were shipped back to Mexico for trade purposes. Spanish missionaries also wanted to claim Native Americans as citizens of Spain. Employing the same philosophy that had driven European exploration for centuries already and would drive European and American colonization for centuries afterward, the Spanish tried to "bring civilization" to the Native Americans who they thought of as backward.

Not surprisingly, Native Americans living in areas in which Spanish soldiers built the various buildings that comprised a mission were suspicious of the intentions of the people living in those buildings. As a settlement grew up around a mission, more Spanish arrived and established pueblos and presidios, the former towns for everyday citizens to live in and the latter forts to protect the towns and the missions. Not for the last time, the local Native Americans living near the San Diego mission protested. The Tipai-Ipai gathered in large numbers and attacked the mission in 1775. The Spanish defended as they could but lost three men, including a padre, or priest. The rebuilt mission resembled a fort more than a center of religious study. One other motivation of Spain's desire to built settlements, religious or otherwise, up the coast of California was that Russia was known to have been exploring farther north, in what is now Washington and Oregon and British Columbia. English explorers were known to have visited the area as well. Spain wanted to protect their interests in New Spain by establishing a populated presence; and in this context, it was no accident that missionaries lived side by side with soldiers. As with other areas of contact and conflict with Europeans and Native Americans, the California mission system was a cultural exchange that also brought with it an exchange of illness. Native Americans living in California had no immunity for measles and other medical maladies that the Spanish brought with them. One particularly vicious strain of measles killed a full one-quarter of the Native American population in the wider San Francisco Bay area in just three months in 1806. As well, some missions subjected the Native American neophytes to labor conditions so harsh that the religious "hopefuls" did not survive. Some estimates are that the Native American population living in and around what became the California mission system declined by nearly one-third. Similar numbers can be found in other areas explored, populated, and conquered, by not only Spanish but also other Europeans. One of the lasting legacies of the missions was the buildings themselves, made of stone, wood, and adobe bricks. Many other buildings in California resembled the mission churches and outbuildings.  Another legacy of the mission period in what is now California was the methods used to supply the missions with water. Even though the missions were never all that far from the coast, they still needed fresh water, something that the Pacific Ocean couldn't provide. Some locations had plentiful potable water; to overcome the paucity of such water in other locations, the Spanish missionaries and soldiers built a series of stone aqueducts, cisterns, and fountains. Mexico's achievement of independence from Spain in 1821 had a great effect on the missions, moving their ownership from Spain to Mexico. The Mexican government secularized the missions in 1833, essentially ending their "mission." The government kept some buildings and land, but most of it passed into private hands. California was part of New Spain, which became part of Mexico. After the Mexican-American War, California became part of the United States. In 1850, California gained statehood. The missions continued on in private hands. In 1865, President Abraham Lincoln signed over ownership of some missions to the Catholic Church. Some missions remain as houses of worship. Many are tourist attractions, and some now include museums dedicated to mission history. |

|

Social Studies for Kids

copyright 2002–2026

David White

Mission San Juan Capistrano, founded in 1776 near what is now San Juan Capistrano

Mission San Juan Capistrano, founded in 1776 near what is now San Juan Capistrano