The Battle of Shiloh

The Battle of Shiloh, also known as the Battle of Pittsburg Landing, was a victory for the Union that solidified recent gains and paved the way for an invasion deeper into Tennessee.

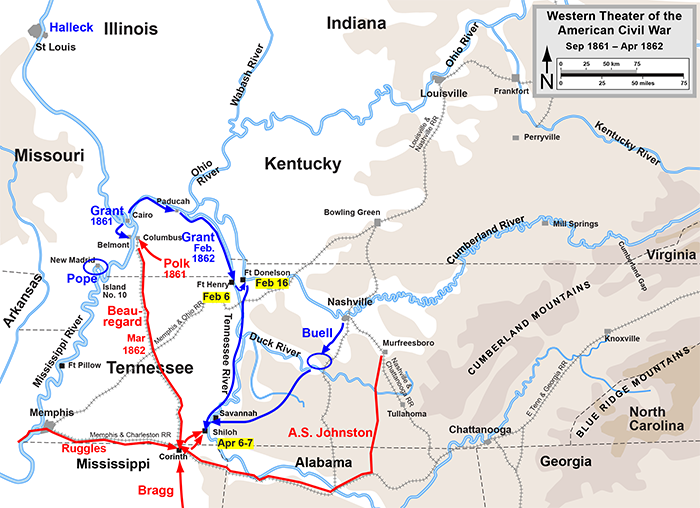

In February 1862, Union forces under Maj. Gen. Ulysses S. Grant had seized control of two Confederate forts, Fort Henry and Fort Donelson.

After taking Fort Henry and Fort Donelson, Grant and his Army of the Tennessee had moved deep into Tennessee. In early April, the army was encamped at Pittsburg Landing, on the western bank of the Tennessee River. Grant was waiting for reinforcements from the Army of the Ohio, led by another major general, Don Carlos Buell. General Albert Sidney Johnston, the Western Confederate commander, knew of the impending reinforcement and wanted to prevent it. He and his second-in-command, Gen. P.G.T. Beauregard, launched a surprise attack on Grant's forces on the morning of April 6. They had come from Corinth, 20 miles to the southwest, and had intended to launch their attack two days earlier but had been delayed by muddy roads. The delay meant that they at the last of their rations before the battle began. The attack commenced around the Shiloh church region. Confederate troops had strong early success on Shiloh Hill and elsewhere, forcing the Union troops to fall back to a series of defensive points, at the church, at Peach Orchard, at Water Oaks Pond, and at a dense thicket known as Hornet's Nest. Johnston's attack plan called for his troops to drive the Union troops into the river to retreat.

The strength of the Army of the Mississippi launching the attack was about 40,000. The size of Grant's Army of the Tennessee was about 44,000. The element of surprise gave the Confederate troops a decided advantage in the early going. However, many on both sides were inexperienced in combat and many who were experienced had not been through the kind of bloody hand-to-hand fighting that ensued; on the Union side were men who had just been through hard fighting at the two river forts. As well, the overall Confederate plan called for coordination that diminished as the battle wore on. In addition, some hungry Confederate troops running through some abandoned elements of the Union camp found still-cooking food too hard to ignore. At midday, Union troops rallied for a counterattack. Johnston was shot in the leg during this counterattack (after taking over from a subordinate who refused to lead his troops into the fighting), and he later died. By the end of the day, Union troops had held their ground but only just: they were on the river. Overnight, from that river, Buell and his 20,000 men arrived. The Confederate troops took charge of the abandoned Union camp. Both sides slept fitfully, their slumber interrupted by a nighttime thunderstorm. The following day, Grant and Buell coordinated an attack between their two armies that drove the Army of the Mississippi away. Beauregard, now in charge, withdrew to Corinth. More than 23,000 soldiers were killed: 13,047 Union and 10,699 Confederate. In addition, Union injured numbered 8,408 and Confederate injured numbered 8,012. At the time, it was the Civil War battle with the highest casualties. |

|

Social Studies for Kids

copyright 2002–2026

David White