Zheng He: China's Greatest Explorer

China's most famous explorer, Zheng He, was born Ma He in 1371 into a large family who lived in Yunnan, then controlled by the Mongols. The sixth child, he followed in his ancestors' and siblings' footsteps and embraced the Muslim faith. His father and grandfather had made the required pilgrimage to Mecca, and they instilled in young Ma He a desire to explore. He was also a well read child, at a young age absorbing the teachings of Confucius.

Ming soldiers, after killing his father in 1381, took the boy hostage. He found himself sent to be a servant in the household of Prince Yan, whose birth name was Zhu Di. The very tall Ma He learned how to fight and served his prince well, fighting in several battles and helping his prince succeed in his drive to seize the throne from his uncle, the Jianwen Emperor. Zhu Di in 1402 proclaimed himself the Yongle Emperor, head of the Ming Dynasty. He named Ma He, his onetime bodyguard, the equivalent of his chief of staff and gave him a new name: Zheng He. The new emperor set about on a series of grand projects, including the construction of the Forbidden City. The most far-flung of these projects was the explorations of Zheng He. He had supervised repairs on the royal palace, and now the emperor wanted him to spread the word of China's greatness to the world.

The ships were some of the largest ever built, and the size of the fleets that went forth were some of the largest ever recorded. Several sources say that the ships were 400 feet long (far longer than others built at the time). The first voyage, 1405–1407, featured nearly 200 ships and 28,000 soldiers. The expressed intentions of the voyage were exploration, trade, and diplomacy; the soldiers were there to protect such enterprises and to impress leaders they visited with the might and awe of China. As a matter of fact, those soldiers were needed because when the fleet was nearly home on that first voyage, they encountered pirates and had to fight their way out of a Sumatran port. In other cases, Zheng He employed his soldiers to protect against land-based marauders.

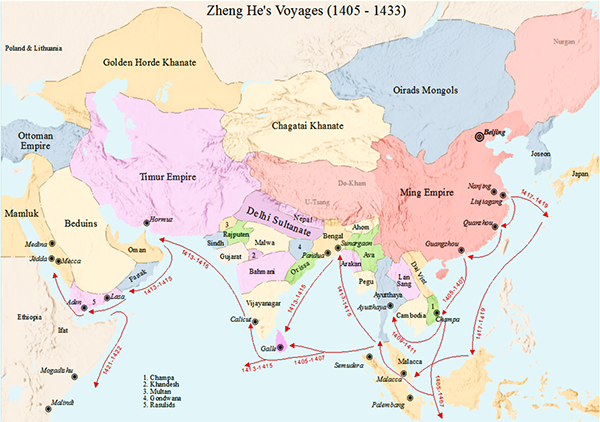

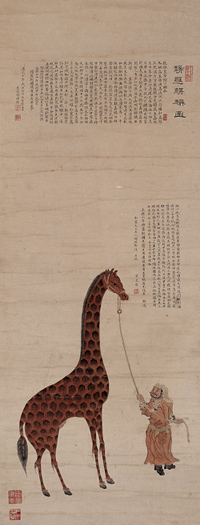

On a total of seven expansive voyages, they sailed into the South Pacific, the Indian Ocean, the Persian Gulf, and along the east coast of Africa. Among the civilizations visited were Brunei, India, Java, Kenya, Indonesia, Malaysia, Saudi Arabia, Somalia, Thailand, and Yemen. In exchange for deliveries of Chinese silk and Ming porcelain, civilizations far and wide agreed to maintain the Chinese tribute system. Among the exotic elements that Zheng He and his sailors brought back home from these voyages were camels, giraffes, ostriches, and theretofore unknown gems and spices. He also returned with other countries' diplomats, eager to see for themselves the might and glory of Ming China. The Yongle Emperor died in 1424. By that time, Zheng He had completed six voyages. The new ruler, the Hongxi Emperor, placed less importance on the things that Zheng He brought back and the prestige that his voyages gained and more importance on the cost that those voyages represented. By this time, the Mongols were threatening again in the north and many people were starving as a result of the not uncommon occurrence of famine. Zheng He was ordered to abandon any further voyages of exploration. The Hongxi Emperor's reign was short, however, and his successor, the Xuande Emperor, approved of sending Zheng He out into the world again. At age 61, the intrepid mariner set forth once again with a treasure fleet, heading across the Indian Ocean to Malindi, near Kenya. On the voyage home, Zheng He died; he was buried at sea. While on that final voyage, Zheng He had ordered his fleet to stop twice and build a stone tablet containing an inscription listing his accomplishments. These tablets are at Changle, in Fujian province, and at Liuhe, a Yangtze River port that was then named Liujiagang.

|

|

Social Studies for Kids

copyright 2002–2025

David White