The Boxer Rebellion

The Boxer Rebellion was an international conflict in China that began as an uprising against foreigners and ended with foreign domination. Throughout the 19th Century, Japan and countries in the West had expanded their influence in China, particularly in the north. Two Opium Wars in the early and mid-19th Century had weakened Chinese military forces and influence. The Treaty of Tientsin, which had ended the Second Opium War, had given Western powers the authority to increase the size of their Christian missionary movements within Chinese borders, including buying land on which to build churches. China had also fought against Japan for control of the Korean Peninsula. In the Treaty of Shimonoseki, which ended the First Sino-Japanese War, China agreed to give Taiwan and another island, Penghu, over to Japan, as well as renounce all claims of influence in Korea. In addition, China handed over the Liaodong Peninsula, which contained the strategic Port Arthur.

Shandong Province, in the east, was particularly hard hit by flooding and famine in the late 1890s; as a result, many farmers went to cities in search of food. Existing discontent with German missionaries, fueled by an ongoing dispute over one religion's building a church on the site of another's former temple, boiled over into violence; and in the Nov. 1, 1897, Juye Incident, a group of angry Chinese men killed two missionary priests. The German leader, Kaiser Wilhelm II ordered German troops to take over Shandong Province. Seeing this, other Western powers moved to expand their influence within China. France and the United Kingdom expanded their presence in a number of provinces, and Russia obtained a controlling role in all territory north of the Great Wall. In June 1898, the Guangxu Emperor embarked on the Hundred Days' Reform, a program of modernization along the lines of what Japan had done after the Meiji Restoration, with the goal of bringing China on a par economically and militarily with Japan and the West. The Chinese defeats in the Opium Wars and the war with Japan had revealed China's military weakness, especially.

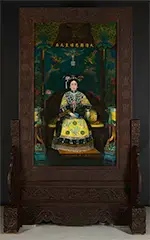

Reactionary forces were still strong in China, however, and many people did not want to change, no matter how much the rest of the world had. One of those resistant to change was the Dowager Empress, known as Cixi. She had assumed a regent's role because the emperor was young. In mid-1898, she seized control of the government and dampened enthusiasm for reform.

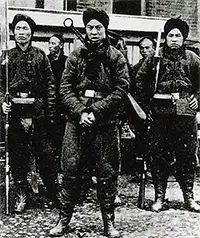

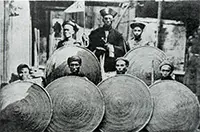

A group of Chinese nationalists who had trained in the martial arts and believed themselves to have special powers organized in the I-ho-ch'uan (Society of Righteous and Harmonious Fists) and attacked people from other countries. Westerners, referring to the martial training methods, called these people Boxers. Many of these Boxers were dispossessed peasants from Shangdong Province. The Boxers as a whole, though, represented areas around the country. They focused their ire not only on foreigners but also on Chinese people who had converted to Christianity, seeing them as having embraced Western ideals. The Boxers originally included the Qing Dynasty in their list of enemies, since the government had embraced so many other nations by way of international treaties. However, the Dowager Empress appealed to the Boxers to join the government in repelling the invading foreigners. They eventually did so. Foreign powers continued to move to consolidate their gains within China in 1899. Boxer forces continued to carry out raids on foreign possessions and attacks on foreigners. In October 1899, at the Battle of Senluo Temple, a Boxer force proved itself eminently able to be killed by bullets and other weapons–dispelling the myth of their alleged superhuman powers. Some in China left the movement; others ignored it. Still, the Boxers, which by that time were calling themselves a militia, had plenty of support and manpower. Their attacks continued. By May 1890, roaming militia forces had reached Beijing. In the next few weeks, Boxer carried out indiscriminate attacks on Christian missionaries and their places of worship. One particular harsh reprisal to a German soldier's sudden killing of an unarmed Boxer boy was a Boxer campaign of demolition of Christian cathedrals and churches, in some cases burning alive people inside.

On June 20, 1890, a particularly large force of Boxers exceeding 100,000 launched a large-scale attack on the capital city, demolishing not only Christian churches but also more secular targets, such as railway lines and stations, and surrounding the part of the city in which foreign diplomats had their residences. Seizing an opportunity to strike back, the Dowager Empress declared her support for the Boxers and declared war on all countries with which her country had formed diplomatic ties. The force that had invaded Beijing was large. The initial battle had killed thousands of Chinese Christians and hundreds of foreigners. Among the dead was Clemens von Ketteler, the German ambassador. In response, the governments of several nations mobilized a military response. The so-called Alliance of Eight sent thousands of troops to Beijing to relieve the siege. The Alliance of Eight were the following:

A force of about 20,000 from those eight nations arrived in Beijing on Aug. 14, 1900, having slogged through Boxer-held territory in northern China to get there. After some fierce fighting, the foreign troops took control of the city. The Dowager Empress and the Guangxu Emperor, who was already in confinement, fled into the mountains. The victorious nations divided the city in order to keep it under control, rooting out vestiges of Boxer power and influence. What was supposed to be a peaceful occupation turned into widespread pillaging and violence, including the destruction of Chinese temples and reprisal executions of suspected Boxers. As well, foreign diplomats seized many artifacts and other valuables from Chinese homes, offices, and museums. In the north, Russian troops occupied Manchuria, after a series of fierce battles. (Russia would hold onto that province, eventually leading to conflict with Japan.) Many in China wanted to continue the war, even though the capital was occupied by foreign forces. The Dowager Empress decided otherwise, and peace negotiations ensued. They dragged on for many months, even as looting continued in the capital. The Boxer Protocol, signed on Sept. 7, 1901, further weakened an already struggling Qing Dynasty:

Death toll estimates vary widely, depending on the source. Many historians say that the number of soldiers killed was a few thousand. Most historians agree that far more civilians died; some sources cite this number as more than 100,000. |

|

Social Studies for Kids

copyright 2002–2024

David White

Government officials who took part in or supported the rebellion were to be punished.

Government officials who took part in or supported the rebellion were to be punished.