The First Sino-Japanese War

The First Sino-Japanese War was a late 19th Century struggle largely over control of Korea, won convincingly by Japan.

The war is known in Japan as the Japan-Qing War, in Korea as the Qing-Japan War, and in China as the War of Jiawu. The empire ruling China in the late 19th Century was the Qing. China had maintained a large military and political presence in Korea for a few hundred years; and for most of that time, China had a strong military and a feared reputation. Two Opium Wars in the early and mid-19th Century, however, weakened Chinese military forces and influence. At the same time, Japan, in 1854, had agreed to open its border and trade with the United States and then, after the Meiji Restoration, embarked on a period of industrialization that produced growth and modernization across all aspects of the country, including its military might. Japan attempted to seal a trade deal with Korea but met with stiff resistance. Some in the Korean government wanted to remove the existing isolation policy (much like Japan’s until recently); others did not. Japan, in particular, wanted access to Korea’s rich agricultural stores and coal and iron deposits. Tired of taking no for an answer, Japan imposed the Japan-Korea Treaty of 1876, following Commodore Matthew Perry’s blueprint and convincing Korea of the wisdom of opening its ports to trade with Japan. As with Japan, Korea soon found itself signing treaties with other countries.

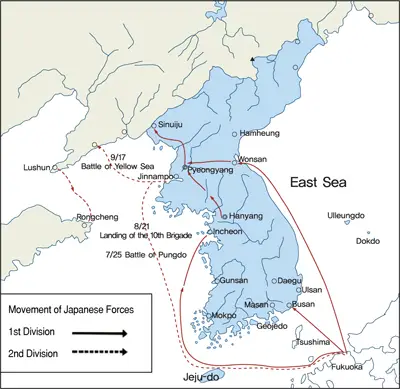

Japan sent four warships and a large amount of land forces to Korea, to demand reparations. China sent a large amount of land forces to make sure that Japan didn’t take over Korea. Tempers flared, but the two armies avoided conflict; instead, the result was the Treaty of Chemulpo, signed on August 30, which required Korea to pay reparations to the families of the Japanese people killed in the uprising. One other condition of this treaty was that Japan insisted on stationing troops at their diplomatic offices in the Korean capital, Seoul. The Korean government continued to be favorable toward China, for the most part, although divisions remained. In 1884, a group of pro-Japanese forces ousted the Korean government; in retaliation, the pro-Chinese forces regained control of the government and, further, burned the Japanese foreign office. Many people were killed in both coups, but the brief fighting did not descend into open warfare. The result once again was a diplomatic understanding, which included the removal of both Chinese and Japanese troops from Korea and the promise from each government that it would let the other know if it intended to return its troops to Korean lands. Four Chinese warships were stopped for repairs in the Japanese city of Nagasaki in 1886. The sailors from those ships incited a riot in the city and killed several Japanese policemen who tried to stop the riot. China offered no apology to Japan after the incident. A few years later, in 1894, a pro-Japanese Korean participant in the coup a decade earlier was assassinated in Shanghai; Chinese officials sent his body back to Korea, where the government displayed it as a warning to anyone else who wanted to plot to overthrow the government. Japan expressed outrage at this. A peasant rebellion in Korea resulted in widespread panic, and China sent nearly 30,000 troops to Korea to quell the rebellion. Japan insisted that it hadn’t been notified of this breach of the 1885 agreement and send a few thousands troops of its own to Korea. (China insisted that it had notified Japan.) In June 1894, the Japanese troops captured Gojong, the Korean king, and occupied the royal palace in Seoul, replacing the government with a very pro-Japanese contingent. The Chinese government refused to recognize the new Korean government, and China and Japan eventually went to war. The fighting began on July 25, 1894, with the Battle of Pungdo. By this time, China had sent most of its forces home from Korea, to deal with a couple of revolts within China. Thus, Japanese forces outnumbered Chinese forces in Korea. As well, the Japanese troops were trained in modern methods of warfare and had modern weapons and ships of war. Thus, the first battle of the war, off the coast of Asan, was a smashing victory for Japan. Japanese forces sunk two Chinese ships and captured a third; one of the ships sunk was a transport, and all 1,100 men aboard were killed or wounded. By the time that war was officially declared, on August 1, the fighting had begun in earnest.

On the very next day occurred the largest naval battle of the war. This battle is known by various names. One most commonly cited is the Battle of Yalu River. The battle took place mainly in the Yellow Sea, near the mouth of the Yalu River, which is on the Chinese-Korean border. Japanese forces destroyed eight of China’s 10 warships, assumed control of the Yellow Sea, and carried on into China itself. Japanese forces occupied the Chinese city of Dandong and then captured several more cities and towns. Elsewhere, Japan laid siege to Port Arthur, seizing the strategic port on November 21. Japan continued to press its advance into China, emerging victorious at the Battle of Weihaiwei after a 23-day siege and a final assault, on February 12, 1895. (A harsh winter had slowed down Japan’s advance.) A few minor skirmishes followed; the occupation of Taiwan’s main settlement of Magong convinced China to sue for peace. The Treaty of Shimonoseki, signed on April 17, 1895, ended the war. According to the terms of the treaty, China agreed to give Taiwan and another island, Penghu, over to Japan, as well as renounce all claims of influence in Korea. In addition, China handed over the Liaodong Peninsula, which contained the strategic Port Arthur. China also agreed to pay a huge amount of silver to Japan as reparations. Overall casualties were about 35,000 killed or wounded for China and about 5,100 killed or wounded for Japan. (Another nearly 12,000 Japanese forces died from disease.) Japan gained in influence throughout the region, as the influence of the Qing Empire waned, both inside China and elsewhere in the world. |

|

Social Studies for Kids

copyright 2002–2024

David White

A severe drought in 1882 in Korea caused food shortages and resulted in financial difficulty; the shortage of funds was so intense that the government was not paying soldiers anymore. A joint military-populace riot on July 23 attacked the government’s rice granaries and the royal palace and then targeted the office of the Japanese foreign minister, killing a few Japanese citizens.

A severe drought in 1882 in Korea caused food shortages and resulted in financial difficulty; the shortage of funds was so intense that the government was not paying soldiers anymore. A joint military-populace riot on July 23 attacked the government’s rice granaries and the royal palace and then targeted the office of the Japanese foreign minister, killing a few Japanese citizens.  Chinese forces retreated to Pyongyang in the wake of a Japanese advance. On September 15, Japan took the city after some heavy fighting that resulted in many more Chinese casualties than Japanese casualties.

Chinese forces retreated to Pyongyang in the wake of a Japanese advance. On September 15, Japan took the city after some heavy fighting that resulted in many more Chinese casualties than Japanese casualties.