|

|

The Life and Successes of Alexander the Great

Part 1: Motives in Motion

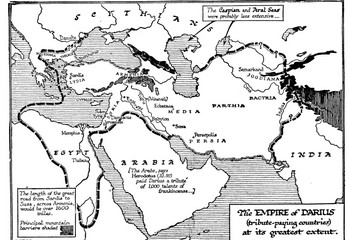

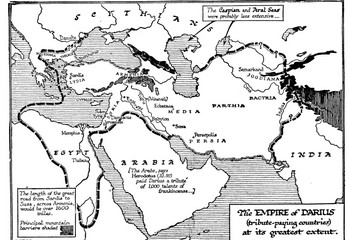

The motivation of Alexander the Great was clear: He wanted revenge for the terrible attacks on Greece that the Persians had wrought under Darius the Great and Xerxes. The purpose of Alexander the Great cannot be agreed on by historians: Did he want to conquer all of Persia? Did he want to teach Darius a lesson? Did he really want to be welcomed as a conquering hero in Egypt and to be looked on by surprise in Bactria and India, so far from the beloved home of his beloved soldiers? Whether he wanted all of these things or not, he got all of them and more.

Greece had weakened the Persian Empire by winning the heroic battles at Marathon, Salamis, and Plataea. But the Greeks soon descended into civil war, from which, technically, Athens emerged the big loser and Sparta the big winner; the reality was that all of Greece lost, for the city-states were too weak after the many years of fighting each other and were ripe for takeover.

Ready to do some conquering of his own was Philip II of Macedon. His civilization at that time was just to the north of Greece proper. Macedon was strong and had strong-minded soldiers, many of whom both envied and despised the Greeks. Philip and his troops moved on Greece, picking off the city-states one by one. Publicly, Philip insisted he was building a federation, one he called the Federal League of Corinth. Privately, however, he coveted  Greece. Greece.

This Federal League was announced and put into action in 338 B.C. This followed the major defeat of the Greeks at the Battle of Chaeronea. Of the major city-states, only Sparta was not involved. (In other words, Philip hadn't conquered Sparta yet.) Philip, however, decided to pursue bigger targets: He wanted a piece of the Persian Empire.

Philip was a brilliant military commander and politician as well. He juggled the warring sentiments of the Greeks long enough to keep them ready for assimilation, then assembled them all under his banner into what was really a kingdom designed as a federation. He was a great tactician, and his plans for invading the Persian Empire were brilliantly executed—by his son.

Philip was assassinated on the eve of his invasion of Persia. His son, Alexander, took over the reins of both army and kingdom and put the invasion plans in motion. He was 21.

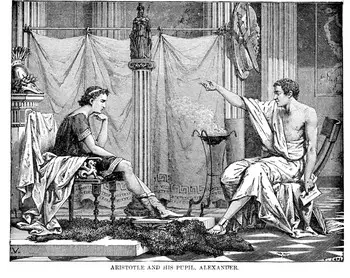

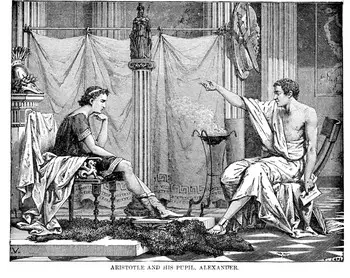

Schooled in war and politics by his father and in everything else by the legendary Greek philosopher Aristotle, Alexander was filled with knowledge of the world and ambition for conquering it. Like his father, he dreamed of defeating the Persians in battle, something the Greeks had been able to do before, but this time on their own soil. In 334 B.C., two years after Philip's death, Alexander led his troops into Asia Minor. Schooled in war and politics by his father and in everything else by the legendary Greek philosopher Aristotle, Alexander was filled with knowledge of the world and ambition for conquering it. Like his father, he dreamed of defeating the Persians in battle, something the Greeks had been able to do before, but this time on their own soil. In 334 B.C., two years after Philip's death, Alexander led his troops into Asia Minor.

Historians disagree on just how many (or how few) troops that Alexander started his invasion with: A generally agreed-on figure is 30,000 infantry and 5,000 cavalry. (These last would come in especially handy. Alexander was a master of the cavalry charge.) Astonishingly enough, Alexander brought with him few fighting ships and very little in the way of treasury. His troops had weapons and food and the hunger for conquest, but that was about it. This would not be the last time that Alexander's determination to succeed despite long odds would be nearly the only thing that carried him to victory.

Next page > Revenge for Past Sufferings > Page 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11

|

|

Greece.

Greece. Schooled in war and politics by his father and in everything else by the legendary Greek philosopher

Schooled in war and politics by his father and in everything else by the legendary Greek philosopher