Slave Rebellions in America

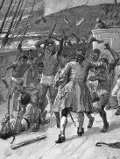

In the long history of slavery in America, millions of African-Americans were taken against their will from their homes in Africa and forced to work in horrendous conditions in the New World. The apparatus of slavery was such that slave owners and overseers had all the power and all of the weapons, for the most part, and so it was very difficult for enslaved people to do anything to change their fate. Some slaves committed acts of passive disobedience, such as feigning illness or unassumingly sabotaging crops, machinery, or operations; others preferred active disobedience, such as refusing to work or otherwise follow orders. Many tried to escape and many were successful, at times traveling along the famed Underground Railroad. Punishments for all of these acts of aggression or resistance to authority were harsh, often resulting in severe injury or death. Another way in which slaves tried to change their fates was to take up arms against their owners. Some rebelled individually or in small groups, with varying degrees of success. Others gathered in larger groups, as many as several hundred. New York City, 1712 Stono Rebellion, 1739 Gabriel Prosser, 1800

Gabriel Prosser was a blacksmith, and he made many of the weapons intended to help facilitate the uprising. This series of events took place in 1799. Prosser was inspired by the revolt of slaves in Haiti several years earlier and took that revolution's motto as his: "Death or Liberty." Prosser set a date of August 30, 1800, for the revolt to take place. The weather on that day was so bad that travel was impossible. Prosser let it be known that the revolt would go ahead the following day. However, some of those involved in the plot told their owners and the state militia was waiting. The would-be rebels dispersed but were quickly rounded up and put on trial. More than 60 slaves faced trial in a court that had no jury but in which witnesses and the accused could provide testimony. Half of those were found guilty and executed. Some were found not guilty. Prosser, who had evaded capture for a few weeks, was cornered and captured. His trial began on October 6. He refused to speak in his own defense. He was convicted and executed. Andry Rebellion A slave named Charles Deslondes led a group of slaves that grew to about 200 (some estimates say as many as 500) in all through the German Coast of the Mississippi, in the area of what is now New Orleans. They stormed through the countryside, burning plantations and killing slaveowners. As with other rebellions, this one came up against a much more well-armed and well-organized militia, and the result was the same–violent deaths for those who rose up in revolt. Deslondes was not given a trial but was summarily executed, in a particularly brutal way. Denmark Vesey Vesey was one of a number of leaders of a slave rebellion that was planned for 1822. It would have been the largest in the history of the country, with as many as 9,000 slaves rising up and killing white men throughout the Charleston area. Vesey set the date as July 14. As with Prosser's failed plot, the undoing of Vesey's rebellion was the sharing of its existence and target date with slaveowners. Local authorities arrested more than 130 people and convicted 67, including Vesey, of insurrection. They were all killed. Nat Turner Revolts at sea

The rebellion aboard the Creole took place in November 1841, when the U.S.-owned ship was on its way from Richmond, Va., to New Orleans. Eighteen of the 135 slaves onboard, led by Madison Washington (who had escaped slavery once before), rose up and seized control of the crew and the ship. They sailed the ship to Nassau, in the Bahamas, which was then controlled by Great Britain, which by that time had outlawed the slave trade. Washington and the other slaves were detained but ultimately released; the slaves who had not participated in the uprising were freed. (The famed former slave and abolitionist activist Frederick Douglass wrote a fictionalized biography of Washington called The Heroic Slave.) Cherokee Revolt The uprising began on Nov. 15, 1842, when the slaves arose before their masters and locked them in their quarters, stole some guns and horses, and rode away. The Cherokee came in quick pursuit and caught up to the runaway slaves; the resulting confrontation was a two-day gun battle. The Cherokee broke off their attack to wait for reinforcements, and the slaves slipped away. The revolt ended in heartbreak for the runaways when their supplies ran out; those who were still living when the Cherokee caught up to them a second time were captured and either tried for murder or returned to slavery. |

|

Social Studies for Kids

copyright 2002–2024

David White

The largest rebellion organized by slaves was the Stono Rebellion. It occurred in 1739. On September 9 of that year, a group of 20 slaves gathered near the Stono River, in South Carolina. After killing the owner of a weapons depot and helping themselves to a load of guns, they set out to the south, with the aim of reaching Florida. They gained more runaways as they went. The slaves killed several slave owners and their families and then burned their homes. The rebels did not make it to Florida. Word quickly spread to the members of the local militia, who armed themselves and confronted the slaves. The result was a violent conflict that ended with the deaths of 44 slaves and 21 non-slaves.

The largest rebellion organized by slaves was the Stono Rebellion. It occurred in 1739. On September 9 of that year, a group of 20 slaves gathered near the Stono River, in South Carolina. After killing the owner of a weapons depot and helping themselves to a load of guns, they set out to the south, with the aim of reaching Florida. They gained more runaways as they went. The slaves killed several slave owners and their families and then burned their homes. The rebels did not make it to Florida. Word quickly spread to the members of the local militia, who armed themselves and confronted the slaves. The result was a violent conflict that ended with the deaths of 44 slaves and 21 non-slaves. One of the less well-known slave revolts was, in fact, the largest revolt in the history of the U.S. It was known as the

One of the less well-known slave revolts was, in fact, the largest revolt in the history of the U.S. It was known as the