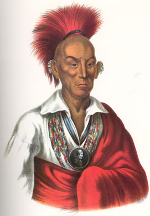

The Black Hawk War raged in 1832 against the backdrop of increasing European settlement in the Northwest Territory, home to Native Americans for generations. The war is named for the Sac (or Sauk) chief Black Hawk, who is thought to have been born in 1767 in the village of Saukenuk in what is now Illinois. Black Hawk became known as a fierce fighter, particularly in his tribe's struggles against the neighboring Osage.

The genesis of Black Hawk's war came in 1804, when Fox and Sac representatives signed the Treaty of St. Louis, which gave up all territory east of the Mississippi River. Many others in both tribes did not believe that the people who signed the treaty spoke for them, and many refused to acknowledge the treaty. In the War of 1812, Black Hawk and many other Sac and many Fox fought alongside British troops, against American troops. British troops had promised the Native Americans lands in the area in exchange for their wartime alliance; that was certainly more than American authorities were offering. Other Native Americans fighting against Americans during this war included the Shawnee and their famous leader Tecumseh. The later alliance of tribes that fought in the Black Hawk War was known to some as the British Band because of their wartime alliances with British troops. More and European settlers moved into the area in and around Saukenuk, Black Hawk's village, in what is now Illinois. In 1831, that increase in settlement became encroachment, as Europeans moved in the equivalent of just next door. Black Hawk had had enough. As in other areas, American settlers had as accompaniment American soldiers. In this, it was Gen. Edmund Gaines who arrived in Black Hawk's home area in early 1832, at the front of a large number of federal soldiers and state militiamen (including a raw recruit named Abraham Lincoln). Black Hawk spoke for his people and initially urged them to move to the western side of the Mississippi River. Black Hawk changed his mind and, on April 5, led his people back across the river, in the belief that members of other nearby Native American tribes and British troops to the north would join in the fight. (He had had such assurances from both parties in the past.) He had the support of a number of Kickapoo, and Meskwaki, and Ottawa, but none of Black Hawk's allies had appeared by the time he and a small force had encountered a group of militiamen. Seeing that he was outnumbered, Black Hawk thought it better to surrender. However, mixed signals at the impending truce conference resulted in the death of one of Black Hawk's warriors, and the surrender offer was revoked. Outnumbered, the warriors routed the militia, in what became known as the Battle of Stillman's Run.

Black Hawk and his men attacked a white settlement at Indian Creek, killing a number of unarmed men, women, and children. This made Black Hawk's enemies more determined to defeat him and might have cost him allies as well. He did find many willing to fight alongside him, however, benefiting from timely alliances with a number of Ho-Chunk and Potawatomi who embraced his cause. Raids on European settlements increased, as did battles between small groups of men, throughout what is now Illinois, Iowa, and Wisconsin. Black Hawk developed a reputation as a skilled commander, eluding capture on a regular basis and winning battles with far fewer men than his opponents. He had a finite number of allies in the end, however, whereas the number of enemies kept growing. General Henry Atkinson, commander of the U.S. forces, had a force of 3,000 shortly thereafter, and they set off in pursuit of Black Hawk. More troops, under the command of General Winfield Scott, were dispatched from Chicago, and a steamboat was sent up the Mississippi to contain any breakout.

On Aug. 1, 1832, the steamboat, the Warrior, found Black Hawk and his followers, trying to cross the river in canoes or on rafts at the mouth of the Bad Axe River. The steamboat fired its cannons at the Sac and Foxes, who stayed on the Wisconsin side of the river. No battle immediately ensued, although a subsequent one, the Battle of Wisconsin Heights, was a resounding victory for the American forces. Black Hawk led a group of his followers further north; others tried to cross the Mississippi. The crossing was intercepted, and the U.S. soldiers and militia killed many men, women, and children who were trying to cross the river. Most of the rest of those who had escaped with Black Hawk fell victim to Dakota Sioux pursuers who had no love for the Sac leader. Black Hawk himself surrendered at Prairie du Chien and was imprisoned for a time, in Virginia. He was later allowed to return home, under the supervision of his Sac rival chief Keokuk, who had opposed the insurrection. A treaty between the U.S. and the surviving Sac and Foxes officially ended the Black Hawk War. The tribes had to vacate a total of 6 million acres of land running along the western bank of the Mississippi, in exchange for $660,000. In the 15-week war, Sac and Fox tribes had lost nearly 500 warriors; the U.S., by contrast, had lost 70. Other future famous members of the U.S. force included Confederate President Jefferson Davis and U.S. President Zachary Taylor. Black Hawk died in 1838. His was the first Native American autobiography to be published in the U.S. (in 1833). |

|

Social Studies for Kids

copyright 2002–2025

David White