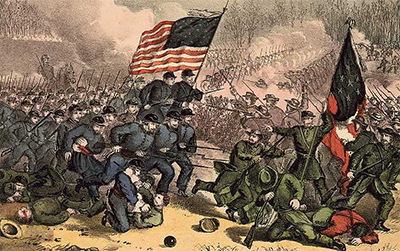

The Second Battle of Bull Run/Manassas

The Second Battle of Bull Run/Manassas was a solid victory for the Confederacy during the American Civil War. It occurred on Aug. 28–30, 1862.

The target for the Union was still Richmond, the Confederate capital. The Peninsula Campaign of Gen. George McClellan had stalled, then resulted in a general retreat. In the meantime, President Abraham Lincoln had relieved McClellan of overall command, replacing him with Henry Halleck, and ordered the creation of a new fighting force, the Army of Virginia, to be commanded by John Pope (right), who had won a pair of hard-earned victories in the West. Pope, in addition, was known as an aggressive commander; McClellan was not. The overall battle plan was for McClellan's Army of the Potomac to meet up with Pope's Army of Virginia; at the very least, Lincoln and Halleck expected McClellan to send a couple of divisions of his men to bulk up Pope's force for an expected encounter with Robert E. Lee's Army of Northern Virginia. Things did not go according to plan. Halleck ordered McClellan to retreat from the Peninsula on August 3; McClellan began his retreat 11 days later. In the meantime, a corps of the Army of Virginia led by Nathaniel Banks attacked the force of Stonewall Jackson at Cedar Mountain on August 9; after an initial period of success, the Union troops retreated across Cedar Creek and avoided defeat only by the timely arrival of reinforcements under Brig. Gen. James Ricketts. Jackson and his troops hunkered down in defensive positions for a few days; Lee then sent a large force led by Gen. James Longstreet to reinforce Jackson's troops. Union and Confederate forces fought in fits and starts along the Rappahannock River for a few days, in action punctuated by the swollen river and muddy banks. By August 25, Pope's force was growing ever larger. McClellan, however, refused to send all of his men to fight for Pope; the cautious "Little Mac" insisted that he needed to keep two divisions to protect Washington, D.C. Lee sent Jackson's men and the cavalry corps of J.E.B. Stuart on a flanking maneuver to sever the Union lines of communication. Jackson's men passed through Thoroughfare Gap on August 26, taking out Bristoe Station on the Orange & Alexandria Railroad line, and then, the following day, helped themselves to as much of the Manassas Junction Union supply depot as they could carry, burning the rest. A stunned Pope ordered a retreat into defensive positioning. Keeping the initiative, Jackson's men headed north to the battlefield for the First Battle of Bull Run/Manassas the year before, setting up in a defensive position in heavy woods behind an unfinished railroad grade on Stony Ridge. Anticipating the likely route of the Union Army, the Confederates lay in wait. Meanwhile, Longstreet's men followed in Jackson's wake, breaking through a small Union force in Thoroughfare Gap on August 28 and racing to Manassas to meet up with Jackson.

On that same day, the Second Battle of Bull Run began. Just outside Gainesville, a Union force marched along the Warrenton Turnpike, having already altered course more than once because of Pope's changing his mind on the best way to approach Manassas. Near the Brawner Farm, Confederate troops opened fire. Jackson had alone appeared on horseback on the road but had been ignored, the Union troops thinking him a lone scout. The fighting continued throughout the day and ended with darkness. Pope, making the first of a series of mistakes, assumed that his men had encountered Jackson's men as the latter were retreating from Centreville. By then aware that Longstreet was approaching, Pope determined to attack Jackson and his men before that linkup could take place. Adding to this urgency were reports from Confederate prisoners that Jackson's men numbered at least 60,000. The situation was so chaotic that Pope did not have an accurate picture of the location of his own troops or the enemy's. Sensing an opportunity for aggressive action, of which he was fond, Pope ordered a full attack for daybreak on August 29. Leading the attack would be Maj. Gen. Franz Sigil, Maj. Gen. Fitz John Porter, and Maj. Gen. Irvin McDowell, who had been the Union commander on the same battlefield a year before.

Not all Union forces were in place when the attack began; as well, the Confederate defenders responded with a series of strong counterattacks. Because of unsureness of his commanders' troop placements, Pope ended up issuing conflicting orders throughout the day. One commander, Maj. Gen. John Fitz Porter, refused to follow the order to attack because he knew that a very large force lay in wait: Longstreet's force had arrived. Fitz Porter knew this because he could see it happening; Pope didn't learn of it until after dark. By the end of the day, neither side had taken or given much ground. The morning of August 30 was quiet, as both Lee and Pope consulted with their commanders before issuing orders. Pope's commanders knew that the Confederate army was not of a mind to retreat or had taken any such action; Pope, however, continued to believe that they were and had. The large-scale attack that Pope ordered resulted in nothing so much as disaster when the usually defensive-minded Longstreet ordered a fierce attack with The fighting was hard, brutal, and long-lasting, particularly on all the last two days. Casualties on the Union side numbered 1,716 dead, 8,215 wounded, 3,893 missing; Confederate numbers were 1,305 dead and 7,048 wounded. To the Confederate side went the victory, and it emboldened Lee to pursue an invasion of the North. The Union side, meanwhile, was embroiled in controversy. Pope blamed his commanders for misinterpreting or not carrying out his orders. He singled out Fitz Porter and had him court-martialed for refusing to follow orders on the second day of battle, even though Fitz Porter had on the last day led an assault that resulted in large-scale slaughter of his troops in the face of withering Confederate artillery fire. The conviction was swift and long-lasting: Only in 1879 did an inquiry ordered by President Rutherford B. Hayes nullify Fitz Porter's court-martial and place the blame on Porter. A despondent Lincoln removed Pope from command on September 12 and restored McClellan to overall command, the Army of the Potomac absorbing the short-lived Army of Virginia. |

|

Social Studies for Kids

copyright 2002–2026

David White

25,000 men against the Union's left flank. Only a heroic rear guard action atop Henry House Hill kept the Union from streaming away in flight, as had happened at the First Battle of Bull Run/Manassas. As it was, the retreat across the water to Centreville was largely successful and gave Lee the field of battle.

25,000 men against the Union's left flank. Only a heroic rear guard action atop Henry House Hill kept the Union from streaming away in flight, as had happened at the First Battle of Bull Run/Manassas. As it was, the retreat across the water to Centreville was largely successful and gave Lee the field of battle.