Roman Britain

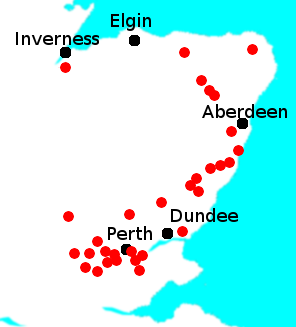

There is a Grampian Mountain range in Scotland, but that is believed to a modern construct borne of a typesetter's mistake. Those mountains weren’t named that until the 16th Century. One more recent argument has been that the fighting took place at Gask Ridge. Remains of an extended earthwork in Perthshire date from A.D. 70. It was 12 miles long and had accompanying forts and watch towers. Quite a lot of scholarship has been put in over the years by people tracking down clues to identify the setting for this epic struggle. These suggested sites match some but not all of Tacitus’s description. Among the lines of historical inquiry is the strong suggestion by more than one eminent historian that the battle never took place at all. The writeup of the battle is certainly slanted heavily in favor of the father-in-law of the man doing the writing. The other thing to note about Tacitus’s account of the battle is that a full two-thirds of the Caledonian force survived the battle. But where did they go? Tacitus said they melted into the “trackless wilds.” And if the results were that stunning, why didn't Rome follow up and press further north? What happened next, relatively speaking, is that the Romans started building a wall. The Roman Emperor Hadrian visited Britain, at the invitation of Governor Quintus Falco, in 122.

After a tour of the countryside, Hadrian decreed that his forces should build a wall the width of northern England, from the River Tyne to the Solway Firth, a distance of 80 Roman miles, or nearly 73 miles. The wall, which took six years to construct, served both as a defensive fortification and, through the use of the gates spaced periodically along, as a customs facility. (It wasn't all fight, fight, fight in those days. Trade did exist between north and south.)

At regular intervals along the wall were milecastles, about a Roman mile apart. Each of these milecastles contained a garrison that housed a few dozen men. In between each pair of milecastles were two towers, also staffed by soldiers on patrol. South of the Wall was a large earthen rampart-and-ditch combination called the Vallum. This earthwork, with its ditch that was 20 feet across and 15 feet deep, was constructed during several decades, at the direction of Agricola and Hadrian and a later emperor named Severus. Archaeologists still don’t agree on the purpose of the Vallum. One theory is that it was the southern boundary of a military zone that was fronted on the north by the Wall itself. Another theory is that it was a construction trench for a road that was never built. There was a road south of the Wall, the Stangate, and it was a communication road. |

|

This battle has been a source of great historical curiosity through the years. For starters, historians can’t agree on where it took place. Tacitus didn’t exactly give coordinates.

This battle has been a source of great historical curiosity through the years. For starters, historians can’t agree on where it took place. Tacitus didn’t exactly give coordinates.  The wall was not the same consistency throughout. In the west, the wall was 3.5 meters high and 6 meters wide and made mainly of turf. In the east, the wall was 15 feet high and 10 feet wide and made of stone.

The wall was not the same consistency throughout. In the west, the wall was 3.5 meters high and 6 meters wide and made mainly of turf. In the east, the wall was 15 feet high and 10 feet wide and made of stone.