|

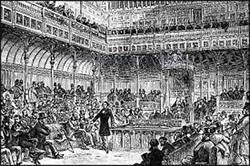

Benjamin Disraeli: the Queen's Prime Minister

Benjamin Disraeli was a two-time Prime Minister of the United Kingdom during the 19th Century. He was known for his warm relationship with Queen Victoria, his commitments to social reforms, and his leadership of the Conservative Party. He was born on Dec. 21, 1804. His family was Jewish. When young Benjamin was 12, he joined the Church of England. He enjoyed a solid education but, rather continue on the path to being a lawyer on which his father had set him, took up writing instead. His first novel, Vivian Grey, was published in 1826. Several more followed: The Young Duke (1831), Contarini Fleming (1832), Alroy (1833), Henrietta Temple (1837), and Venetia (1837). He wrote 17 novels and various works of drama, poetry, and nonfiction. Disraeli did eventually enter politics, running for Parliament three times before finally succeeding, in 1837, representing Maidstone. He joined the Conservative Party. His maiden speech was a rambling mess, according to many who heard it. Early in his career, he was known as an outsider. He married in 1839, to Mary Anne Lewis. They had no children. Two years later, he changed constituencies, winning election to represent Shrewsbury. Disraeli was one of a number of reform advocates who in 1842 formed the Young England group, with aims to forge an alliance between the working class and the upper class in order to counter the growing power of the middle class. He had another three novels–Coningsby (1844), Sybil (1845), and Tancred (1847) published; leading characters in those books spoke out against ill treatment of poor people and for the need for electoral reform. At the same time, Disraeli spoke out harshly against the repeal of the Corn Laws. Opposition to this repeal came from within the Conservative Party, despite the fact that the Prime Minister at the time, Sir Robert Peel, was a Conservative. As a result, even though the Corn Laws were repealed, Peel felt like he didn't have the support of his political party and resigned. Succeeding Peel as Prime Minister was Lord John Russell, a Whig. He, in turn, resigned in 1852; and the new Prime Minister, Lord Derby, appointed Disraeli as Chancellor of the Exchequer. His stint was brief, as was his next serving in the same job, six years later; in between, he served in the opposition. In 1858, Disraeli became leader of the House of Commons. He held this position for a year, then lost it when the Liberal Party again took power. Derby, again Prime Minister in 1866, again named Disraeli Chancellor of the Exchequer. One of the issues that was consuming many in the U.K. in the 1850s and 1860s was electoral reform. The Reform Act 1832 had expanded the voter rolls by a few hundred thousand, but the number of people who could Disraeli was Prime Minister for most of 1868, succeeding to the post when Derby resigned, but gave way to William Gladstone at that end of that year. Six years later, the Conservatives were in the majority again and Disraeli was again Prime Minister. He and the Conservatives enacted reforms of their own, including the Factory Act, Public health Act and Pure Food and Drugs Act–all geared toward improving the lives of people across the economic spectrum. Unlike Gladstone, whom Queen Victoria did not at all like or appreciate, Disraeli enjoyed a cordial relationship with the queen. He was fond of writing her letters to update her on matters of state, and she was fond of writing him in return. Disraeli it was who convinced the queen to style herself Empress of India. It was also true that Disraeli and Gladstone physically and intellectually disliked each other. Each relished in leading the opposition to the other, and their debates and disagreements dominated the political discussions within Parliament and without for a few decades. In 1876, Queen Victoria named Disraeli Lord Beaconsfield. He was Prime Minister at the time, but having the title meant that he could join the House of Lords whenever he wished. He enjoyed success abroad, navigating through a minefield of competing interests at the end of a war between Turkey and Russia and managing to keep the peace and also obtain the island of Cyprus. Also during this tenure, British troops won wars against Afghanistan and the Zulus. Perhaps Disraeli's crowning triumph in foreign relations was to gain a large amount of ownership in the Suez Canal, thereby protecting U.K. trade to and from India and other points east. The loss in the general election of 1880 was particularly hard on Disraeli, and he fell ill. He published his last novel Endymion, in 1880. He died on April 19, 1881. He was 76. |

Social Studies for Kids |

Social Studies for Kids

copyright 2002–2026

David White

vote was still a small minority of the overall population. Liberal Party leader

vote was still a small minority of the overall population. Liberal Party leader