Part 5: The Making of a Legend

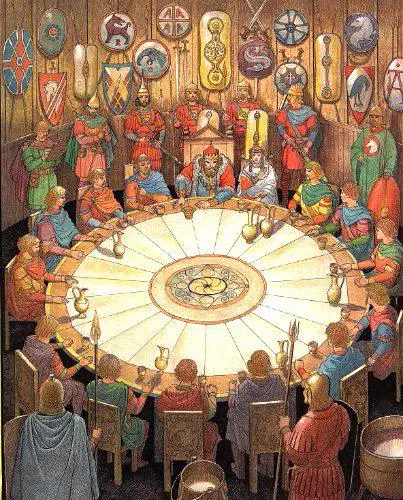

Later writers built on this tradition. Of particular note was Chretien de Troyes, a Frenchman who introduced to the Arthur story the names Camelot and Lancelot, which were Arthur's chief court and chief knight, respectively. Other medieval writers added on more now-familiar elements, including the Round Table (so that no knight would be more important than any other) and the Holy Grail (the cup that featured in Christianity's Last Supper). Stories about Arthur appeared all over Europe and then all over the world, in many languages.

With the advent of archeology in the 19th Century, scientists began to search for proof of Arthur's existence, in the form of physical evidence of the Battle of Badon Hill or the Battle of Camlann. Some discoveries have given historians hope of finding more evidence, but the proof from archeology of the historical existence of Arthur and his accomplishments is still very, very slight. Historians cannot even agree that Arthur was a man's first name. One theory is that Arthur is a melding of two other words and that Arthur was a title.

With the advent of archeology in the 19th Century, scientists began to search for proof of Arthur's existence, in the form of physical evidence of the Battle of Badon Hill or the Battle of Camlann. Some discoveries have given historians hope of finding more evidence, but the proof from archeology of the historical existence of Arthur and his accomplishments is still very, very slight. Historians cannot even agree that Arthur was a man's first name. One theory is that Arthur is a melding of two other words and that Arthur was a title.

The common story that has come down to modernity–of King Arthur and his Queen, Guinevere, and his noble knights meeting around the Round Table at Camelot and then going off on a quest for the Holy Grail–is, many scholars think, a collection of legends, of things that never were or events that never happened; rather, historians think, the stories are just that, stories, that have survived because they are entertaining and captivating and give hope to those who hear them and read them.

The facts are that the Britons, with someone leading them, defeated the Saxons a number of times in the 5th and 6th Centuries, before the Saxons began to take over more fully. Whether it was a man (or even a king) named Arthur leading the Britons remains to be seen. By the 6th Century, however, the Saxon takeover of the British Isles was kicking into high gear.